Has America Given Up on the Dream of Racial Integration?

Across the country, communities are starkly divided, with African Americans living in one section and whites living in another, and a lot of people seem to be okay with that.

BEAUMONT, Tex.—There are termites everywhere in this first-floor apartment near the railroad tracks. They’re on the windowsill and in an elongated nest on the ceiling. They’re flying into water glasses and expiring there, landing on food and beds and clothing, playing a Mother-May-I game every time you turn your back.

The apartment shakes when trains go by, blowing their horns through the night, and a cement-crushing plant a block away spews up clouds of dust and residue that coat windows and front porches. The tenant, who didn’t want to give his name because he said the Housing Authority has a reputation for evicting people for petty reasons, said he tries to keep things neat, but he’s no match for the bugs, dust, and mold.

The public-housing property, called Concord Homes, is not a good place to live, and in many cities, a similar disaster would have been torn down decades ago. But the funds to do so have gotten caught up in a battle about whether federal and state government have the right to tell Beaumont to integrate its neighborhoods, a fight that seems pulled from an earlier era.

Just about every resident of Concord Homes is black and poor—the average annual income there is $6,716 per household. But when the Beaumont Housing Authority received $12.5 million of federal money to build new homes for the people who live there, the city refused to build anywhere but this particular footprint, which is located in a census tract where 87 percent of the population is black and half live in poverty. Housing advocates said that rebuilding this public-housing property in an area of high poverty, where almost all other public-housing residents live, did not “affirmatively further” fair housing, a goal that the federal government has been required to promote since the Fair Housing Act in 1968. There are also environmental hazards nearby, including the rail lines, a shuttered steel plant, and the concrete-crushing plant.

After a multi-year battle among the Beaumont Housing Authority, housing advocates, the Department of Housing and Development (HUD), and the Texas General Land Office, the city of Beaumont said it would rather give up the funding than build homes for these people in a richer and whiter part of town. HUD is now assigning the money to other communities and Beaumont has to find its own money to renovate Concord Homes, if it chooses to do so.

The Fair Housing Act became law in 1968, a week after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Its goal was to prevent landlords and lenders from turning away tenants and homebuyers because of their color, but Senator Edward Brooke, one of the sponsors of the bill (and the first black man elected to the U.S. Senate), had bigger ideas. He wanted to use the law to integrate cities and suburbs, reversing the effects of decades of housing discrimination, discrimination that had often been perpetuated by the federal government.

“American cities suffer from galloping segregation, a malady so widespread and so deeply embedded in the national psyche that many Americans, Negroes as well as whites, have to come to regard it as a national condition,” Brooke said in 1968. “The prime carrier of galloping segregation has been the Federal Government. First it built the ghettos, then it locked the gates, now it appears to be fumbling for the key.”

But America could do better, Brooke believed. Federal laws could make it possible for black residents living in inner cities to move to areas with better schools, decent homes and good jobs, simply by making it illegal to refuse qualified tenants on the basis of race. HUD could give money to cities and states to build public housing in areas outside of “Watts, Hough, Hunter’s Point and ten-thousand other ghettos across the land.” The federal government could withhold funding from cities dead-set against integration, and make sure its money went to help build a country where blacks and whites live together, side by side.

“This measure, as we have said so often before, will not tear down the ghetto,” he said. “It will merely unlock the door for those who are able and choose to leave.”

In many places, America seems to have given up on that vision. Affluent neighborhoods throughout the country resist the construction of affordable housing in their backyards. White residents self-segregate, and though poverty might not be limited to urban areas, it is often the most concentrated where minorities live. In places such as Beaumont, federal funding to build homes for black residents in white areas is lost because neither white nor black residents want that to happen.

“This town is caught in the 1950s,” Janice Brassard, a former school-board member, told me.

Laws to promote integration have been rolled back as the memories of the civil-rights era fade. The Roberts Court struck down parts of the Voting Rights Act and ruled that the country no longer needs race-conscious policies to remedy past wrongs. And sometime this month, it will rule on a part of the Fair Housing Act, in a case referred to as Inclusive Communities, in which Texas is challenging the rulings of lower courts that it acted illegally in locating affordable-housing complexes in low-income, minority areas.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts wrote in a 2007 opinion that struck down a voluntary public-school desegregation program.

And yet, in the absence of the legal muscle to overcome it lives on here in east Texas. This is an area where, in nearby Vidor, a 1993 attempt to integrate public housing was met with Ku Klux Klan marches; where, in the nearby town of Orange, a group is building a Confederate Memorial off of Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, which will feature dozens of Confederate flags visible from I-10; where 12 members of a white-supremacist gang called Solid Wood Soldiers were arrested and indicted as recently as 2013.

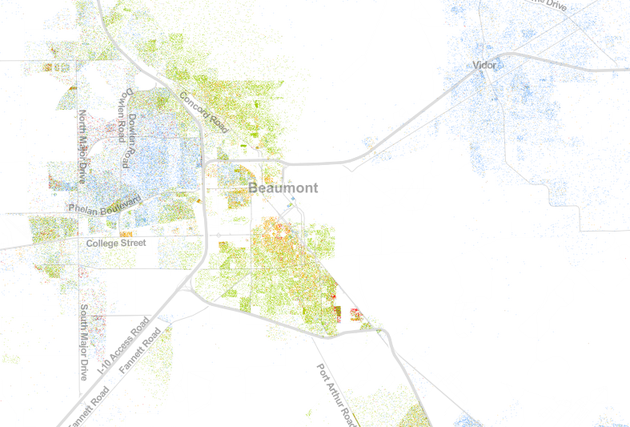

In 2010, white residents made up about 40 percent of Beaumont’s population, while black residents made up about 47 percent. Black and white residents go about their lives separately, unless the state or federal government intervenes. The city seems to have resigned itself to the idea that “integration will never work in Beaumont,” said Maddie Sloan, an attorney for Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit that litigates on behalf of low-income families.

“It is apartheid, the type of stuff that goes on in the real world out there in mid-sized cities today,” said John Henneberger, a fair-housing advocate in Austin who sued the state of Texas over its planned use of disaster-recovery funds.(Henneberger recently won a MacArthur Genius Grant.)

“At some point,” he said, “HUD and the Department of Justice and some other folks have to blow the whistle, but they don't unless somebody's out there raising hell about it.”

Highways divide Beaumont (population: 118,000) into three sections — the North End, the West End, and the more amorphous south, where downtown is located. The north and south are poor and predominantly black and Latino, the west is wealthy and predominantly white. According to census data, the most populous tract in the West End is 76 percent white, has a median family income of $82,153. The area on the north side where Concord Homes is located has median family income of $19,861 and is 79 percent black.

Deshawn Smith learned firsthand the differences between the north and west sides of town when she moved to Concord Homes two years ago from the west side. Her eldest daughter had loved school at Amelia Elementary, on the far west side. When the girl started second grade at her new school on the north side, the teacher called Smith and expressed surprise that her daughter could read—no other second-graders could read at all. (Smith moved because her boyfriend went to jail and she could no longer afford a West End apartment on her own.)

“My 8-year-old says she learns nothing at this school and she doesn’t like it,” Smith told me, standing outside her Concord Homes apartment as the same daughter quietly listened. “The teacher got mad at her in class and said she only comes for a paycheck anyway.”

Housing integration has always been a controversial topic. An increasing amount of data indicates that children of low-income families who are moved to so-called “high-opportunity” areas achieve higher levels of education and have better jobs than their counterparts who stay in poor areas. But low-income neighborhoods need investment too, and some housing advocates argue that taking federal housing dollars from poor neighborhoods to build affordable housing in nicer neighborhoods causes the poor areas to struggle even more.

Still, HUD is required to “affirmatively further fair housing,” and it is difficult to argue that keeping Concord Homes in the North End does so. Much of the North End is zoned for industrial use, and there’s an asphalt plant under construction on one side of Concord Homes and a citywide school-bus parking lot on the other. Railroad tracks run through many streets on the north side, and trains constantly stop traffic on their way to the port, their cars labeled “liquefied petroleum gas.” Many of the area’s one-story houses are peeling, and many streets lack sidewalks or underground drainage. There are pawn shops but the last central grocery store closed last month, part of a plan by the chain H.E.B. to open a new store much farther to the south. The Housing Authority began moving families out of Concord Homes when it thought it was getting federal money to renovate the complex, now that it has lost the money, the complex is half-abandoned and barely maintained.

The West End, by contrast, has mega-grocery stores and fancy restaurants, wide roads with traffic lights, sidewalks, and drainage.

All of the public elementary schools in Beaumont’s north side were rated “F” by a state group called Children At Risk; the only two elementary schools in the Beaumont Independent School District that received grades of “A” or “A-“ are located in the West End (one school in the very north part of the city did receive a “D”).

Even low-to-moderate income families have trouble achieving upward mobility in Beaumont. Community Bank of Texas, a Beaumont bank, made just one loan to low-to-moderate income families in 2012, according to a letter sent to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. By contrast, all lenders in the Beaumont market collectively issued 17.1 percent of their loans to low-to-moderate income families that year. The same bank issued just one prime loan to African American borrowers in Beaumont in 2012, while all lenders in the city issued 8.2 percent of their loans to African American borrowers.

When different races don’t interact, racism tends to be exacerbated, and Beaumont is no exception. The culture of Beaumont, and indeed, much of east Texas, seems to encourage local leaders to merely shrug when racial tensions emerge.

In 2011, for instance, a black worker at a Goodyear tire plant in Beaumont allegedly returned to his locker to find a figure of a black man eating a watermelon and a noose. He filed a racial-discrimination suit, and his attorney Peter Costea told me that when he talked with witnesses in the case, he was shocked at what he learned: Black and white employees worked on separate sides of the plant, and the black side was hotter because, employees were told, “they are used to the heat.” The complaint details other alleged incidents at the plant, including when another noose was hung in the open, when graffiti depicting swastikas appeared in the plant’s bathroom and cafeteria, when a letter was found in a desk drawer stating “niggers are lazy,” when a supervisor said he disliked “nigger President Obama and also that all niggers thought that they were running the country now,” and when a comment was written on a safety card that slavery should still be legal. The plaintiff also alleged that he had not been hired as a full-time Goodyear employee, but was instead kept a contract employee for seven years because of his race. He eventually asked Costea to drop the lawsuit because he was struggling with depression after the incident, Costea said.

But when I asked Michael Getz, a Beaumont city-council member, about racism in Beaumont and the incident at the Goodyear tire plant, he played it down.

“Someone played a practical joke, and it was in poor taste and stupid,” he told me. “Do things like happen from time to time here? Sure. It happens across the country. How many times can you pick up a newspaper and read that somebody found a noose in the workplace?”

Getz and the Beaumont Housing Authority have argued that moving families to a wealthier neighborhood is a strategy dreamed up by outsiders who don’t know what the people of Beaumont want. The North End is in need of development, they say, and the city is spending money there to make it a better place to live—rebuilding Concord Homes would further that mission. They say the area has seen $282 million in recent investment, including new schools, new parks and recreation facilities, and newly renovated public housing properties. Plus, the Housing Authority argues, residents want to stay on the north side, near their churches and their families.

Had Beaumont been able to build on the existing footprint with HUD funding, the Housing Authority would have been able to avoid debt, said Robert Reyna, the head of the Housing Authority. They conducted testing on the ground soil near the asphalt plant and said it didn’t show any signs of health hazards. In addition Reyna said that new restaurants and businesses are opening in the North End, though all I could find was a new Dollar General and a few fast food restaurants.

As a last-minute attempt to compromise, the Housing Authority proposed a plan to build 100 units in a high-opportunity area, but only 50 would be public housing. It planned to still rebuild Concord Homes. The state rejected this plan because it did not promote fair housing, and because it eliminated 50 units of public housing.

The head of the local NAACP sent a letter to the state in support of the Housing Authority’s plan. The NAACP also supported rebuilding Concord Homes on its current footprint, Sloan said.

“Forced integration is never going to work anywhere,” Reyna told me. “I think that as people choose where they want to live, whether it’s in an impacted neighborhood or not, you have to respect people’s choices.”

Getz puts it differently.

“You should be willing to help people who can't help themselves,” he told me. “But they’re not necessarily entitled to live in the West End.”

The Beaumont Housing Authority’s history of resisting integration efforts casts doubt on whether Beaumont ever really stopped believing in the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

In 1982, HUD sued 36 counties in East Texas, including Jefferson County where Beaumont is located, over their failure to integrate public housing. The suit was resolved by a consent decree in 1987, but Beaumont still resisted taking actions to integrate its housing, despite HUD money provided to the city in 1992 to develop a few units of affordable housing in desegregated areas. By 2000, little of that housing had been built and HUD took over the Beaumont Housing Authority.

“Civil rights deferred are civil rights denied,” then-HUD secretary Andrew Cuomo said at the time, in a press call recommending that a nearby city take over Beaumont’s Housing Authority.

Little had changed by the time Hurricane Ike swept through Beaumont in 2008. Texas received $1.7 billion in funds for hurricane recovery, but was not awarding the grants in a way that “affirmatively furthered fair housing,” according to a complaint filed by Henneberger’s organization, Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, and Texas Appleseed. A 2010 settlement between the housing advocates and the state required these funds to be distributed in ways that led to more integration, and allowed the groups to review applications for disaster funding to make sure the state complied. Beaumont’s plan to rebuild Concord Homes in a high-poverty area using those funds violated the agreement.

The state did its own review, and agreed that Beaumont could not rebuild on the site, and HUD agreed. The state offered Beaumont an additional $1 million to rebuild elsewhere, bringing the total figure of external money for rebuilding Concord Homes to $13.5 million, a huge sum for a housing authority to receive. (A senior housing property with 126 units was recently proposed for the city’s more expensive west side for $14 million.)

The Beaumont Housing Authority also proposed to sell off the individual units of affordable housing it had built, which were some of the only places that low-income residents could live in public housing that was not located in the North End.

Reyna is right that many in Beaumont—including Concord Homes residents—say they don’t want to move. Local African American pastors urged Henneberger and HUD to allow Beaumont to rebuild Concord Homes on its current location.

“The African American pastors said, ‘Look, just let them do this, because this is Beaumont—we tried integration back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it didn't work,’” Henneberger told me.

I spent some time at Concord Homes, and many residents said they just wanted the city to rebuild the units. They didn’t care where they were located, they said, though many complained about the trains and the dust and the disrepair.

“If they’re coming to take the hospitality to rebuild for us and our kids, and they're building us a new apartment, how are we going to complain about where they build it?” said one woman, who didn’t want her name used because she said people get kicked out of public housing for lesser causes.

I asked a group of women in a north-side park about moving Concord Homes and they agreed that residents should stay put.

“Why does everything got to go to the West End?” one woman, who identified herself as Miss Y, told me. “Why would they take from the North End and put it way across town?”

It’s true that the North End could use a whole lot more investment. But this has been true for a long time, and little has changed. The city repaved 7th Street, which runs through downtown and up into the North End, but stopped the work where the street enters the North End, said Tai Ho, the managing attorney at Lone Star Legal Aid in Beaumont. An effort to repave Concord Road, which runs through the North End, has been delayed multiple times. And there’s no way to stop trains from idling in the North End for hours at a time, blocking roads (I saw one train sit still, blocking an intersection for an hour, which residents told me was typical).

When I asked Michael Getz about whether the West End could ever see similar industrial developments, he said no, because it wasn’t zoned for light industrial use.

“That area has been zoned light industrial forever, and homes sprung up around there historically because at the time, that's all they were allowed to buy,” he said, about the North End. “That’s how neighborhoods were created in the pre-Civil Rights era. And now we're going to move everyone out of there? I don't see that as a practical situation.”

Ho, the Legal Aid attorney, said he was surprised by the degree to which North End residents seem to accept that they are relegated to a more toxic and blighted area of town than white residents. He likens it to “battered-spouse syndrome.” Residents in Beaumont put up with things that people in other parts of Texas would push back against, he told me. They regularly cede their security deposits because landlords say they’ve been living in the apartments for more than five years, which the landlords say means they must have created a lot of damage, he said. Residents of public housing get written up for stacking dishes on the counter rather than in cupboards or taking too long to fold their laundry. One low-income resident was allegedly nearly kicked out of her apartment for disobeying a posted sign and saying negative things about the Housing Authority in a public area, Ho said. North End residents feel that they couldn’t possibly move to the west side, because they don’t belong there, he told me.

“The community as a whole is hoping for separate but equal—but I don’t see it as equal at all,” he told me. “I see it as what they are resigned to—it permeates throughout the community: You’re getting assistance, be happy about it and shut up.”

In January, a black Beaumont man who was in a relationship with a white woman found the letters “KKK” written on the back of his car in white shoe polish, according to a local news station. It was the second such incident that week. A surveillance video showed a white man running out of a white pick-up truck and writing the letters.

In March, when a developer made a presentation about putting an affordable housing complex for seniors on the city’s West End, community members asked, at a public meeting, “Why do you want to come to an area where nobody wants you?” which drew applause from the audience. Another resident called him a “carpetbagger.”

And last week, an African American councilman said publicly that he was a victim of racism when residents objected to his application for a permit to open his law office in an area near downtown. Residents had circulated an email about the councilman’s plan to open his office, complaining that they didn’t want “pimps and thugs” in their neighborhood. Another African American councilman said he had heard disparaging remarks made about areas of town where black residents lived three times since January.

As the school district has struggled, many white families have moved to Lumberton, a town to the north. Changes to the racial composition of the West End are met with suspicion. Janice Brassard, who lives on the west side, told me that after a black family moved in on one side of her house and a Latino one moved into another, she was asked “multiple times” when she was selling her house “because the West End is being invaded.”

But residents of the North End are still stuck there for the time being. After losing $12.5 million of HUD funding, the Beaumont Housing Authority vowed to renovate Concord Homes with its own money. Residents were told renovations could begin in the next 18 months. For now, they’ll put up with noisy trains and termite nests, rattling trucks and a half-empty housing development.

The city of Beaumont has other things to worry about. Last month, the Department of Justice sued the city for violating another part of the Fair Housing Act in the way it built group homes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The city says it has done nothing that is against the law.