Key Points

-

Highlights the increasing UK population being prescribed drugs that might affect the periodontal tissues.

-

Reviews the more common drugs that can cause changes in healthy and inflamed periodontal tissues.

-

Describes the clinical changes that may be observed.

-

Considers the clinical relevance of these issues in general dental practice.

Abstract

This paper reviews the effects that drugs may have on the gingival and periodontal tissues. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth has been recognised for over 70 years but is becoming a more prevalent occurrence with wider use of antihypertensive and immunosuppressant drugs. The anti-inflammatory steroids, non-steroidal drugs and anti-TNF-α agents might all be expected to exert a dampening effect on chronic periodontitis although the evidence is somewhat equivocal and none of these drugs has emerged as potentially valuable adjuncts to treat periodontal disease. Desquamative gingivitis is a clinical appearance of aggressive gingival inflammation with which a number of drugs have been associated and the oral contraceptives have also been implicated in the development of gingival inflammation. Patients who are prescribed bisphosphonates and anti-platelet drugs are at risk of serious side effects following more invasive dental procedures including extractions and surgical treatments although timely, conventional management of periodontal disease may be undertaken to reduce periodontal inflammation, prevent disease progression and ultimately the need for extractions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The healthy periodontium is a functional and biological unit that comprises numerous different cell types (for example, fibroblasts, macrophages and inflammatory cells) and connective tissue components (fibres and an extracellular matrix) as well as a rich microvasculature and neural complex. This dynamic, anatomical compartment retains the ability to undergo physiological turnover and remodelling and as such, may be influenced by the actions of a number of drugs. Similarly, when the periodontal tissues are affected by inflammatory disease they become host to many pro-inflammatory cytokine networks which may in turn be affected by drugs that patients may be taking for other medical conditions.

Although the data of total number of patients in the population regularly taking these medications do not appear to be readily available, we have made an estimate of the frequency of a number of medications discussed in this review, using data from the UK Biobank cohort. The UK Biobank is a cohort of 500,000 people between the ages of 40-69 collected between 2006 and 2010, which is reportedly demographically representative of the UK population.1 There are currently approximately 31 million people over the age of 40 and taking the figures from the UK Biobank data we have calculated estimates of medication use from this2 (Table 1).

Further, 10 million people in the UK are over 65 years old and projections suggest that by 2050, this population will have nearly doubled to around 19 million.3 One in six of the UK population is currently aged 65 and over and by 2050 this will be one in four. Most people over 65 live with a long-term medical condition,4 and most people over 75 live with two or more.5,6 Such common and chronic conditions such as hypertension necessitate the prescription of often multiple medicines and in 2013 for example, 1.0 billion prescription items were dispensed in the UK: an increase of 3% (30 million items) on the number dispensed in 2012.7 Further, the demand for organ transplants in the UK is increasing and this will continue as the population continues to age and with an increasing prevalence of obesity and diseases such as cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and those related to alcohol consumption. The number of transplants undertaken in 2012-13 was over 4,200.8

The general dental practitioner is thus often faced with patients with increasingly complex medical histories which may affect their periodontal and oral health. The aim of the paper is to review the more common drugs that can affect the periodontium either in its healthy or inflamed condition.

Gingival overgrowth

Gingival overgrowth or gingival enlargement are terms used to describe drug-related gingival lesions that have previously described as gingival hyperplasia or gingival hypertrophy; gingival overgrowth is an overarching clinical description which does not necessitate a diagnosis based upon the histologic composition of the affected gingival tissues.

Drug-induced gingival overgrowth (DIGO) or enlargement is a well-recognised condition that has been researched extensively over the last four decades. Three types of drugs in particular have been reported as associated with DIGO, namely phenytoin, ciclosporin and calcium-channel blockers. The clinical appearances of DIGO show similar features irrespective of the drug or drugs that are causative (Table 2). The first signs of change occur about 1-3 months after the start of dosing and there would appear to be minimal threshold plasma levels of the drugs below which DIGO is unlikely to occur.17,25,26 The interdental papillae become swollen with a granular, pebbly surface which may enlarge further to become nodular and lobulated as the tissues coalesce to affect the marginal and attached gingiva. The overgrowth predominantly affects the buccal and labial gingiva in the anterior regions of the mouth.27 The enlargement will compromise the clinical crown height possibly to the extent of totally obscuring the crowns of the teeth and thus interfering with appearance, speech and function. Interproximal enlargement may displace adjacent teeth causing tooth migration and the emergence of diastemata. DIGO can also affect edentulous areas of the mouth while previously unaffected edentulous mucosa may develop DIGO if dental implants are placed in the tissues.28,29 Although DIGO is often firm and healthy in appearance, the enlargement will often compromise severely the standard of plaque control leading to inflammatory change: oedema, bleeding on probing and erythema. Such an appearance is particularly seen when the overgrowth is superimposed upon a pre-existing chronic periodontitis.

Reports of the prevalence of DIGO for these three drugs are extremely varied although the prevalence of the condition for phenytoin and ciclosporin are around 50% and 30% respectively (Table 3). The variability of these figures may be due to a range of factors including the type of patients recruited, the length of time they have been on the drug, the doses used and the criteria for defining and measuring the overgrowth. In general, however, there is good evidence to suggest that the prevalence and severity of DIGO may be associated both with dose of the drug used, and the level of periodontal inflammation and dental plaque present.

Pathogenesis

Unlike many of the conditions that affect the periodontal tissues the pathogenesis of DIGO may be regarded as a modification of the normal physiological processes that regulate the turnover of the periodontal tissues. The precise mechanisms by which a number of drugs with quite diverse pharmacokinetics are able to create similar clinical changes are still poorly understood but studies particularly with phenytoin suggest that subjects who are susceptible to DIGO have populations of periodontal fibroblasts that are unregulated to produce increased amounts of collagen and/or extracellular connective tissue matrix31 (Table 2). Similarly, regulation of complex array of enzymes that underpin collagen turnover (matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases) may also be responsible for producing a histopathology that is characteristic of DIGO.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin is an anticonvulsant prescribed for the control of epilepsy and neuralgias first introduced in the 1930s and the side-effect of gingival overgrowth was first reported soon afterwards.32 In the present day, phenytoin is not usually prescribed as a first line drug for the management of epilepsy due to the availability of a wide range of newer, more effective anticonvulsant drugs with fewer side effects. Estimations of the total number of patients in the UK population taking phenytoin in the population are in the tens of thousands (Table 1). Other anti-convulsant drugs have not been reported to cause DIGO. Therefore most patients who take phenytoin either take it because it has successfully managed seizures for a patient for many years, and therefore there is no reason to risk destabilising seizure control for the patient, or it is used in combination with other anticonvulsants or because seizure control has proven refractory to other drugs in patients with difficult or complex epilepsy syndromes.

Ciclosporin

Ciclosporin was initially produced in the 1970s as an antimicrobial agent but its immunosuppressive effects on T-lymphocytes were recognised almost immediately and it is now used to prevent graft rejection in solid organ transplant patients as well as for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, pemphigus, pemphigoid, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. The association between ciclosporin and DIGO was reported in the early 1980s.33 Post-renal transplantation patients may frequently be found to be taking both ciclosporin and a calcium channel blocking drug such as nifedipine, and this may have synergistic effects on the severity of the DIGO seen.34 The calcium-channel blocker verapamil, however, appears to have no augmenting effect on the severity and prevalence of ciclosporin-induced gingival overgrowth.35

Although the use of ciclosporin for the prevention of graft rejection following organ transplantation transformed the success of these lifesaving surgical procedures, other drugs, notably tacrolimus, which does not appear to be associated with risk of DIGO, are increasingly used for the management of graft rejection post-transplantation rather than ciclosporin.

Calcium-channel blockers

Calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) are a very widely prescribed group of anti-hypertensive drugs. They are classified into two sub-groups: the dihydropyridines such as nifedipine, amlodipine and felodipine which have been particularly associated with DIGO; and the non-dihydropyridines such as diltiazem and verapamil which have been described in case reports to be associated with DIGO, but generally less consistently. CCBs interfere with the influx of calcium ions through cell membranes and by doing so cause relaxation of smooth muscle and induces vasodilatation of the coronary and peripheral vasculature. The link with gingival overgrowth was first reported in 1984.36

As with other drugs associated with DIGO the reported prevalence of nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth varies widely between 5-80%. One of the most extensive community-based studies in the UK published in 1999 found a prevalence of 6.3% of moderate-severe DIGO in over 400 patients taking nifedipine whereas the prevalence of moderate-severe overgrowth in patients taking either amlodipine (1.7%) or diltiazem (2.2%) was not significantly different from that seen in a cohort of control (0%) subjects. The prevalence of DIGO was also three times greater in males than in females.37 Empirically, as secondary care receivers of periodontal referrals, we see increasing numbers of patients with mild gingival swelling and marked increase in periodontal inflammation associated with amlodipine therapy, which also rapidly improves in cases where the drug is changed to a non-CCB drug. For example, currently around 12% of all patients referred for periodontal assessment at Guy's Dental Hospital are taking amlodipine, which is considerably over double the percentage one would expect to occur purely by chance. Subjectively, these cases often have a less fibrous appearance than those of other cases of DIGO. Given these anecdotal observations and the fact that around 1.5 M people in the UK now take amlodipine, it is possible that this is an emerging important issue in periodontology and urgently requires further study.

Other classes of anti-hypertensive drugs do not appear to be associated with risk of DIGO. These include angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors, such as ramipril, enalapril, lisinopril), angiotensin receptor blockers (such as losartan, candesartan), diuretics (such as hydroflumethiazide and frusemide) and β blockers (such as propanol and atenolol).

Management

Management of DIGO depends particularly on local measures including plaque control, control of inflammation and may also require surgical intervention. In addition consideration has to be given as to whether it may be possible to alter the causative drug on some occasions.

The Basic Periodontal Examination for a patient with DIGO will invariably produce scores of 4, at least in the anterior sextants. Radiographic examination is essential to determine to what extent if any the periodontal bone support has been compromised and whether the DIGO is a solitary change or one that is superimposed upon an underlying chronic periodontitis that also requires treatment. An intensive programme of plaque control with scaling and prophylaxis is the first line of treatment followed by root instrumentation in cases where there has been loss of clinical attachment. In many cases of less severe overgrowth this conventional approach will be all that is required. Where aesthetics and/or function are compromised and resolution of the overgrowth is not apparent, then surgical reduction of the excess tissue is an option. However, long-term recurrence will occur in around 40% of cases if there is no change in drug treatment.38

There is some evidence in the literature that removal of the offending drug by substitution often results in marked improvements in the gingival condition39,40,41,42 and this published evidence is also backed up by our own anecdotal observation in our clinics.

In considering whether to explore whether changing the medication is possible and desirable, it is important to emphasise that this decision rests with the prescribing physician and the dentist's role is only to discuss this with the physician. The decision by the physician to substitute medication in this way depends on assessment of the potential benefits against the medical risks. In particular simply because an alternate drug is available does not mean that this will be without consequence in all cases. For example, in the case of someone with long standing seizure-free epilepsy, one consequence of having a single seizure would be a ban from driving a vehicle for a minimum of one year. Similarly it is self-evident that loss of prevention of graft rejection post-organ transplantation could be life-threatening. Thus the opportunity to substitute medication where a patient takes either ciclosporin or phenytoin should be played down with the patient, although it is perfectly reasonable to explore the possibility with the physician if the overgrowth is severe.

In the case of CCBs and hypertension, as noted above, there are many other classes of anti-hypertensive which may be effective in blood pressure management without causing gingival symptoms. Where the patient already requires a number of different medications to control their blood pressure, or post-myocardial infarction, where CCBs are used also to increase coronary artery blood flow, there may be no opportunity to substitute the 'offending' medication. In all cases the emphasis needs to be on effective communication between the dentist and the physician which is not conducted solely via the patient.

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Periodontal diseases comprise a group of inflammatory disorders that are driven by microbial challenge (biofilm) and have a complex pathogenesis that has been associated with the imbalance between the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as the interleukins and tumour necrosis factor,43,44,45 and prostaglandins,44,45 and the moderating effect of protective anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10.46 The inflammatory nature of the diseases would also suggest that their onset and progression might be affected in those patients who are taking anti-inflammatory drugs for other conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis as well as autoimmune diseases, ocular, skin or renal conditions. The drugs that have been studied most often with respect to periodontal diseases are the corticosteroids, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and more recently, biological therapies such as anti-TNF-α which are effective as biological therapies for conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids such as prednisolone, prednisone, betamethasone and dexamethasone are used widely through medicine predominantly for the treatment and palliation of chronic inflammatory conditions. The effects of prednisone on the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease was evaluated in a study of patients with multiple sclerosis who had been on long-term steroid medication for 1-4 years. The magnitude of probing depths and the extent of gingival recession and periodontal bone loss was no different in the patients receiving the steroid therapy to cohorts of controls. The researchers concluded that long-term corticosteroid therapy had no obvious influence on periodontal disease.47 An earlier study of gingival inflammation and periodontal destruction seen in patients on long-term steroids also demonstrated that the drugs had no effect on the severity periodontal condition and particularly when compared to the standard of oral hygiene.48

NSAIDs

Prostaglandins, eicosanoids and the leukotrienes are produced from cell membrane fatty acids through a series of enzymatic pathways: firstly by the action of phospholipase on the membrane phospholipids to produce arachidonic acid, and then through the actions of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) to produce the pro-inflammatory mediators.

The first study to evaluate the potential effect of NSAIDs on periodontal status recruited 22 subjects who had been taking the drugs for periods of one year or more. This group had significantly less gingival inflammation and shallower pocket depths than an age-matched control group of only 22 subjects and there was a trend also for there to be less loss of attachment in the group taking the NSAIDs. These results were interpreted as indicating that anti-inflammatory drugs may influence the response of the periodontal tissues to plaque by blocking the production of prostaglandins in the tissues.49

Another study compared the dental radiographs of 75 patients with a five-year history of arthritis and NSAID therapy to radiographs of 75 healthy volunteers. The patients on NSAIDs had significantly fewer sites of bone loss than did the healthy controls and the mean percentage bone loss for the entire dentition was also lower in the NSAID group, although the difference was not statistically significant. They concluded that the inhibition of alveolar bone loss was due to the long-term ingestion of the NSAIDs aspirin and indomethacin.50

While there seems to be a logical argument to support the hypothesis that NSAIDs will influence favourably the periodontal tissues, the complexity of the pathogenesis of periodontitis means it is unlikely that blocking only one pro-inflammatory pathway will result in significant clinical benefit for patients who are taking long-term NSAIDs. Nevertheless, these studies were no doubt the basis for the wealth of clinical trials that followed in the 1980s and 1990s that investigated whether NSAIDs might be used therapeutically for the treatment of periodontal diseases.51 To date, no such adjunct has been developed; systemic dosing is accompanied with a range of (mainly gastrointestinal) unacceptable, unwanted effects and local, oral applications are largely ineffective.52,53

Anti-TNF therapies

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) is a powerful, pro-inflammatory cytokine that is produced by a range of inflammatory and immune cells and which regulates and triggers the production of other cytokines and itself promotes inflammation, tissue destruction and bone resorption.54 By means of this contribution to the innate and adaptive immune responses TNF-α plays a crucial and fundamental role in protecting against the challenge of periodontal pathogens such as A. actinomycetemcomitans and evidence from animal studies suggests that dampening the effect of TNF-α by using anti-TNF-α therapies may actually help to sustain the inflammatory reaction in periodontitis.55

Animal studies also suggest, however, that TNF-α plays an important role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and inhibitors of the cytokine (the anti-TNF-α drugs pentoxifylline and thalidomide) seem to have a protective effect on the periodontal tissues.56 Animal studies also suggest that TNF-α, among other cytokines, may be important in the 'conversion' of gingivitis to periodontitis.57 Further, TNF-α is likely to underpin the commonality of aspects of the aetiopathogeneses of periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis54 and the potential effects of anti-TNF-α drugs on the periodontal tissues have been evaluated in patients with arthritis in an almost identical way to how NSAIDs were first studied in the early 1980s.

The findings of the original study showed that the anti-TNF-α drug infliximab may inhibit bone resorption in patients at risk from periodontal disease although probing depths were unaffected and remarkably, the severity of gingival inflammation was increased.58 These apparently dichotomous findings were unexpected but thought to reinforce the concept that the superficial gingival inflammation and deeper periodontal destruction may represent two separate components of the disease pathogenesis.59

Comparative studies of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were receiving anti-TNF-α therapy as regular infusions of infliximab showed that the biological therapy appeared to offer a degree of protection to patients with periodontal inflammation who had less bleeding on probing, attachment loss and shallower probing depths when compared to patients with arthritis but no infliximab therapy.60,61 Interpretation of these findings58,60,61should be made with extreme caution as the studies recruited relatively small numbers of patients and the effect on bone was not evaluated. Further, while this is of some interest with respect to those patients who are on concurrent anti-TNF-α therapy for arthritic and other disease, it is highly unlikely that such highly expensive drugs will be used for the management of periodontal diseases in the foreseeable future. Anti-TNF and other anti-cytokine therapies are, however, becoming an increasingly routine therapy for the management of rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic inflammatory diseases such psoriasis, and thus will increasingly be taken by some patients within a normal general dental practice.

Desquamative gingivitis

Desquamative gingivitis is a clinical term that is used to describe a particularly aggressive type of gingival inflammation that is associated with a number of conditions such as plasma cell gingivitis, an acute exacerbation of erosive or atrophic lichen planus or benign mucous membrane pemphigoid (Fig. 1). It may also present as a more severe and widespread manifestation of a drug-induced lichenoid eruption; drugs that have been implicated include chlorpropamide, tolbutamide (both sulphonylureas used to treat type 2 diabetes), metformin and propanolol and atenolol (beta-adrenoreceptor blocking drugs that have many indications including hypertension, arrhythmias, heart failure and myocardial infarction). These drug-induced gingival changes are, however, rare but where there are problems, the causative drugs can usually be substituted by an alternative medicine.62 Such cases are best managed by specialist referral in the first instance to identify the underlying aetiology and then the most appropriate treatment regimen.

Oral contraceptives

The effects of the sex hormones oestrogen and progesterone on the periodontal tissues have been studied extensively for over 60 years and the physiological changes in these hormones during pregnancy, puberty and menstruation appear to be a modifying factor for the response of the gingiva to dental plaque.63 Pregnancy gingivitis, which affects approximately 35-100% of pregnant women64 and resolves after birth, is thought to be associated with pro-inflammatory effects of the hormones by increasing the production of prostaglandins, vascular permeability and the influx of neutrophils in the tissues. There is now some evidence, however, to suggest that oestrogen may also have a protective effect65 and that the periodontal inflammatory changes may not necessarily be linked to changes in levels of cytokines and prostaglandins in the tissues.66 Nevertheless, the observation of an increased prevalence of gingivitis in pregnancy without an increase in plaque is now supported by robust evidence of a systematic review.66

The physiological changes in levels of sex hormones are mimicked to some extent by the pharmacological action of the combined oral contraceptives that contain progestogen (1.5 mg/day) and a dose of ethinylestradiol in the range of 30-40 μg/day; doses considerably lower than earlier formulations. This is a highly effective form of contraception and used to control fertility by 25% of women aged 16-49 years and is therefore one of the most widely prescribed drugs in the UK.67 Interestingly, the British National Formulary doesn't list gingival changes as side effects of these drugs, perhaps recognising that this may not be a direct effect of the drug on healthy tissues but an exacerbating effect on a pre-existing, plaque-induced gingival inflammation.

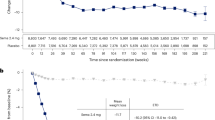

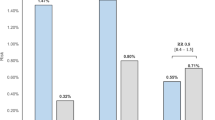

Our understanding of the long-term effects of low-dose hormonal contraceptives on the periodontal tissues is less well reported but should be of potential concern given the prolonged periods over which these drugs may be prescribed. One study compared groups of women who had been taking hormonal contraceptives for up to four years with a matched control group of non-users with similar plaque levels confirmed that use of contraceptives increased gingival inflammation (Fig. 2) but also produced significantly greater loss of attachment.68

Based on the available evidence, therefore, it is important that we make our patients aware of the potential influence that oral contraceptives may have on the periodontal tissues and to ensure that preventative programmes of enhanced plaque control are introduced to establish low levels of plaque at the beginning of contraceptive therapy.66

Bisphosphonates

The bisphosphonates comprise a group of analogues of pyrophosphates that inhibit osteoclastic activity to produce a powerful anti-resorptive effect. The drugs may be administered orally or by intravenous infusion and the main indications are for the treatment of post-menopausal osteoporosis, Paget's disease, and hypercalcaemia and bone metastases associated with multiple myeloma and breast cancer. The bisphosphonates licensed for use in the UK are (in order of increasing potency): etidronate (Didronel); clodronate (Bonefos, Clateon, Loron 520); pamidronate (Aredia); alendronate (Fosamax, Fosavance); ibandronate (Bondronat, Bonviva); risedronate (Actonel); and zoledronate (Aclasta, Zometa). Zoledronate is approximately 10,000 times more potent than etidronate (Corgel) and is given as an intravenous infusion for the treatment of Paget's disease and to limit bone resorption in advanced malignancies.

One of the potential side effects of bisphosphonates is osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), a debilitating condition that includes signs that may be evident in the periodontal tissues: exposed alveolar bone, persistent, non-healing ulcers, mobile teeth and unexplained soft tissue infections.69 This has been particularly associated with those receiving intravenous (as opposed to orally administered) bisphosphonates. The reports of the incidence of ONJ following intravenous bisphosphonate administration must be considered with caution. A prospective, two-year longitudinal study of over 1,000 patients receiving intravenous zoledronate to reduce the incidence of hip fracture following hip surgery found no cases of ONJ and thus suggests an extremely low risk.70,71 Conversely, a cohort of nine subjects with ONJ had all received intravenous bisphosphonate for metastatic bone disease and all nine had undergone extraction of periodontally-affected teeth before the development of necrosis of the jaws.69 These latter observations in particular indicate the need for raised awareness when providing periodontal treatment for patients who are prescribed bisphosphonates and the reader is referred to excellent guidance for practitioners in primary care that has been produced by the Scottish Dental Clinical Development Programme.72 The clear recommendation is, whenever possible, to undertake periodontal treatment to eliminate infection and improve the standard of home plaque control before bisphosphonate therapy is commenced. Invasive surgical procedures should be avoided if possible although some authorities have suggested that if these are indicated then bisphosphonate therapy can be discontinued temporarily to reduce the risk of ONJ although such a 'drug holiday' or 'drug vacation' must only ever be considered after consultation with the patient's medical team.

The placement of implants also involves manipulation of the alveolar bone and bone remodelling is essential for successful osseointegration. Implant success, safety and the incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw have been assessed in prospective and retrospective studies of 140 patients on oral bisphosphonates with no reported cases of ONJ.73,74 Conversely, however, there is evidence of an increased failure of dental implants in patients taking long-term bisphosphonates.75 So although implants are not contra-indicated in these patients, they must be clearly informed of the potential risks of ONJ and implant failure, the need for regular reviews as part of a recall programme, and consented appropriately.71,76 For a more extensive review of the use of implants in patients undergoing bisphosphonate therapy, the reader is referred to a more detailed review by Javed and Almas.77

From the periodontal point of view, bisphosphonates have proved to be a double-edged sword. Any drug whose action is to prevent the resorption of bone might be considered to have immense potential in treating a disease where bone is resorbed as a consequence of periodontal inflammation. Indeed, animal studies have reported clear benefit of both intravenous and topical bisphosphonates in preventing bone resorption in plaque-induced periodontitis78,79,80 and implants treated with ibandronate have been shown to increase biocompatibility of the implant surface, promote the formation of the adjacent bone, and accelerate osseointegration when compared to non-treated implants.81 Human studies have also shown a positive effect of bisphosphonates in slowing the progression of bone resorption in periodontitis82,83,84,85 although intra-muscular injections of neridronate as an adjunct to non-surgical management of advanced chronic periodontitis failed to show any significant benefit over root instrumentation alone.86 Many of the human studies are relatively short-term and with equivocal findings. It is unlikely that these drugs will be licenced for treatment of periodontal disease in the foreseeable future.

Anti-platelet drugs

These drugs reduce the tendency for platelets to aggregate and are primarily used for the treatment of established cardiovascular disease, the prevention of atherothrombotic events and the treatment of myocardial infarction. Two of the most commonly prescribed drugs are clopidogrel and aspirin which are prescribed at doses between 75 mg-300 mg and are often used in combination. The drugs have different modes of action: aspirin is a cyclooxygenase inhibitor that blocks the production of thromboxane A2 whereas clopidogrel blocks ADP receptors on the platelet cell membranes. Both drugs carry a risk of an increased tendency to bleeding during or following periodontal surgery87 and this risk is far greater when the drugs are used in combination.88,89 This risk has been demonstrated by the report of a case of critically severe and life-threatening gingival bleeding following scaling and root instrumentation of the maxillary teeth in a patient prescribed aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) following coronary angioplasty and stent insertion.88

Of course the 'double-edged sword' described previously for the bisphosphonates also applies to anti-platelet drugs in that platelet inactivation will see a reduction in platelet-derived, pro-inflammatory cytokines which theoretically will interfere with the progression of periodontitis. Animal studies have shown that systemic administration of aspirin or clopidogrel attenuates inflammation, reduces neutrophil invasion, reduces bone resorption and decreases attachment loss in experimental periodontitis.89,90,91 Further, the findings of a case-control study of almost 400 subjects on doses of aspirin (<300 mg/day) suggest that the drug has a protective effect on loss of attachment although the recognised association of the drug with gingival bleeding will prohibit the realistic development of the drug as an adjunct to conventional periodontal treatment.92

In contrast to anti-platelet drugs, patients who are taking anti-coagulant drugs such as warfarin do not appear to suffer from increased gingival bleeding, although of course they may present management issues for the dentist during therapy owing to increased risk of post-operative bleeding.

Statins

Statins, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, are taken to lower cholesterol and are some of the most widely prescribed drugs in the UK (Table 1), particularly in those of middle age and above at risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition to their cholesterol lowering properties they also have strong anti-inflammatory properties and may stimulate bone growth.93 In view of these properties there has been some discussion concerning whether statins may have a beneficial effect on periodontal disease.

Comparing patients who are taking statins against those who are not to determine any possible effect on periodontal disease is subject to considerable methodological difficulties because of the many other confounding factors which might distinguish these two groups and which might also affect their periodontal disease experience94 and therefore any data obtained this way needs to be viewed with some caution. However, there are some limited data that periodontal patients taking statins may have reduced periodontal disease or risk of tooth loss compared to those who are not, although this is not a consistent finding.94,95,96,97

Results from rodent models of periodontal disease also support the possible protective effect of statins on periodontal bone loss.98,99 In addition, some small experimental human studies where periodontal patients were given statins either systemically or topically also support this hypothesis.100,101,102 Although overall these data are interesting, they do not have any direct impact on the management of periodontal patients for the clinician and certainly it is not currently proposed that statins are suitable to be considered as an adjunctive periodontal therapy.

Anti-Cancer treatments

A number of drugs that are used for the treatment of malignant diseases may also affect the periodontal tissues. Cytotoxic chemotherapy is widely used for the management of a very wide range of malignancies. These drugs are typically given by a series of intravenous infusions, and target dividing cells. They typically have a range of acute effects including in the oral tissues,103 and frequently result in transient neutropenia, which can markedly exacerbate existing periodontal disease.104,105

Newer drugs used for the management of cancer may also have effects on the periodontal condition. Tamoxifen, a drug which inhibits oestrogen signalling, is widely taken by many patients with breast cancer, and given the important role of oestrogens in maintenance of bone mass and on gingival tissues, it might be expected to affect the periodontal condition. However, perhaps surprisingly, a recent systematic review found no reports of the effects of this drug on the periodontal tissues.106

A whole generation of novel drug treatments for cancer are now being introduced, which target cellular signalling mechanisms including inhibitors of growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and inhibitors of their intra-cellular signalling pathways, known as protein kinase inhibitors. These drugs include bevacizumab, sunitinib, and pazopanib, but the list of such drugs is ever increasing. Generally there are few reports of the oral effects of these drugs, although there are reports of increased periodontal disease with pazopanib medication. In general oral side effects of new drugs may often be under-detected during initial clinical trials and the dentist should be alerted to the possibility of any of these new medicines causing oral and periodontal side effects. If in doubt the dentist could refer the patient for specialist advice, and may also report the possible adverse reaction by the Yellow Card scheme, which now offers online reporting.107

Overall many patients receiving cancer treatments may have adverse effects on their oral health. These observations emphasise the importance of adequate oral and periodontal care both before and during all of these treatments.104,108

Conclusion

Numerous drugs are known to have an effect on the periodontal tissues by causing pathological change, by dampening the inflammatory pathways involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease or by potentially compromising the management of patients with these conditions. As the number of our patients being prescribed such drugs is increasing each year, the dentist needs to be aware of these effects, how best to manage the patients and when to seek advice from specialist and medical colleagues.

References

Biobank UK. Available at: http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ (accessed September 2014).

UK National Statistics. Theme: Population. Available at: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/hub/population/ (accessed September 2014).

Cracknell R . The ageing population. Key issues for the New Parliament 2010. Available at: http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons/lib/research/key_issues/Key-Issues-The-ageing-population2007.pdf (accessed September 2014).

Banks J, Breeze E, Lessof C, Nazroo J (eds). Living in the 21st century: older people in England. The 2006 English longitudinal study of ageing (wave 3). London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2008.

Barnett K, Mercer S, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B . Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380: 37–43.

Melzer D, Tavakoly B, Winder R, Richards S, Gericke C, Lang I . Health care quality for an active later life. Improving quality of prevention and treatment through information: England 2005 to 2012. A report from the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry Ageing Research Group for Age UK. Exeter: Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Exeter. Available at: http://medicine.exeter.ac.uk/media/universityofexeter/medicalschool/pdfs/Health_Care_Quality_for_an_Active_Later_Life_UpdatedAug2013.pdf.

Prescription Cost Analysis, England (2013). Health and Social Care Information Centre. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB13887 (accessed September 2014).

Organ Donation and Transplants. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Epost@parliament.uk. Number 441, September 2013.

Hassell T M, Hefti A F . Drug-induced gingival overgrowth: old problem, new problem. Crit Rev Oral Pathol Med 1991; 2: 103–137.

Johnson B D, Narayanan A S, Preters H P, Page R C . The effect of cell donor age on the synthetic properties of fibroblasts obtained from phenytoin-induced hyperplasia. J Periodontol Res 1990; 25: 74–80.

Modéer T, Mendez C, Dahllöf G, Auduren I, Andersson G . Effect of phenytoin medication on the metabolism of epidermal growth factor receptor in cultured gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontol Res 1990; 25: 120–127.

Liu T Z, Bhatnegar R S . Inhibition of protocollagen prolive hydroxylases by Dilantin®. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1973; 42: 253–255.

Moy L S, Tan E M L, Holness R, Uitte J . Phenytoin modulates connective tissue metabolism and cell proliferation in human skin fibroblasts culture. Dermatology 1985; 121: 79–83.

Pernu H E, Knuuttila M L E, Huttenen K R H, Tiilikainen A S K . Drug-induced gingival overgrowth and class II major histocompatibility antigens. Transplantation 1994; 57: 1811–1813.

Williamson M S, Miller E K, Plemons J, Rees T, Iacopino A M . Cyclosporine A upregulates interleukin6 gene expression in human gingiva: Possible mechanism for gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol 1994; 65: 895–903.

Iacopino A M, Doxey D, Cutler C W et al. Phenytoin and cyclosporine A specifically regulate macrophage and expression of platelet-derived growth factor and interleukin1 in vitro and in vivo: possible mechanism of drug-induced overgrowth. J Periodontol 1997; 68: 73–83.

Tipton D A, Stricklin G P, Dabbous M K . Fibroblast heterogeneity of collagenolytic response to cyclosporine. J Cell Biochem 1991; 46: 152–165.

Kataoka M, Shimizu Y, Kunikiyo K et al. Cyclosporin A decreases the degradation of type I collagen in rat gingival overgrowth. J Cell Physiol 2000; 182: 351–358.

Barclay S, Thomason J M, Idle J R, Seymour R A . The incidence and severity of nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol 1992; 19: 311–314.

Lucas R M, Howell L P, Wall B A . Nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. A histochemical and ultrastructural study. J Periodontol 1985; 56: 211–215.

Fujimori Y, Maeda S, Saeki M, Morisake I, Kamisaki Y . Inhibition by nifedipine of adherenceand activated macrophage-induced death of human gingival fibroblasts. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 415: 95–103.

Nery E B, Edson R G, Lee K K, Pruthi V J, Watson J . Prevalence of nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Periodontol 1995; 66: 572–578.

van der Wall E E, Tuinzing D B, Hes J . Gingival hyperplasia induced by nifedipine, an arterial vasodilating drug. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1985; 60: 38–40.

Mariani G, Calastrini C, Carinci F, Bergamini L, Calastrini F, Stabellini G . Ultrastructural and histochemical features of the ground substance in cyclosporine Ainduced gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol 1996; 67: 21–27.

Hallmon W W, Rossman J A . The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth. A collective review of current concepts. Periodontol 2000 1999; 21: 176–196.

Nishikawa S, Taha H, Hamasaki A et al. Nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia: a clinical and in vitro study. J Periodontol 1991; 62: 30–35.

Marshall R I, Bartold P M . A clinical review of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Aust Dent J 1999; 44: 219–232.

Silverstein L H, Kock J I, Lefkove M D, Garnick J J, Singh B, Steflik D E . Nifedipine-induced gingival enlargement around dental implants: a clinical report. J Oral Implant 1995; 21: 116–120.

Bredfeldt G W . Phenytoin-induced hyperplasia found in edentulous patients. J Am Dent Assoc 1992; 123: 61–64.

Informational Paper. Drug-associated gingival enlargement. J Periodontol 2004; 75: 1424–1431.

Hassell T M, Page R C, Narayanan A S, Cooper C G . Diphenylhydantoin (Dilantin) gingival hyperplasia: Drug-induced abnormality of connective tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1976; 73: 2909–2912.

Kimball O . The treatment of epilepsy with sodium diphenylhydantoinate. J Am Med Assoc 1939; 112: 1244–1245.

Calne R Y, White D J . The use of cyclosporin A in clinical organ grafting. Ann Surg 1982; 196: 330–337.

Starzl T E, Weil R, Iwatsuki S et al. The use of cyclosporin A and prednisolone in cadaver kidney transplantation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1980; 151: 17–26.

Cebeci I, Kantarci A, Firatli E, Carin M, Tuncerö . The effect of verapamil on the prevalence and severity of cyclosporin-induced gingival overgrowth in renal allograft recipients. J Periodontol 1996; 67: 1201–1205.

Lederman D, Lumerman H, Reuben S, Freedman P D . Gingival hyperplasia associated with nifedipine therapy. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984; 57: 620–622.

Ellis J S, Seymour R A, Steele J G, Robertson P, Butler T J, Thomason J M . Prevalence of Gingival Overgrowth Induced by Calcium Channel Blockers: A Community-Based Study. J Periodontol 1999; 70: 63–67.

Ilgenli T, Atilla G, Baylas H . Effectiveness of periodontal therapy in patients with drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Long-term results. J Periodontol 1999; 70: 967–972.

Dahllöf G, Axio E, Modéer T . Regression of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth after withdrawal of medication. Swed Dent J 1991; 15: 139–143.

Dahllöf G, Modéer T . The effect of a plaque control programme on the development of phenytoin-induced gingival overgrowth. A 2year longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol 1986; 13: 845–849.

Khocht A, Schneider L C . Periodontal management of gingival overgrowth I the heart transplant patient. A case report. J Periodontol 1997; 68: 1140–1146.

Hernández G, Arriba L, Lucas M, de Andrés A . Reduction of severe gingival overgrowth in a kidney transplant patient by replacing cyclosporin A with tacrolimus. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 1630–1636.

Cetinkaya B, Guzeldemir E, Ogus E, Bulut S . Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in gingival crevicular fluid and serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2013; 84: 84–93.

Salvi G E, Lang N P . Host response modulation in the management of periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32 Suppl 6: 108–129.

Preshaw P M, Taylor J J . How has research into cytokine interactions impacted our understanding of periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38: 60–84.

Cochran D L . Inflammation and bone loss in periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2008; 79 Suppl 8: 1569–1576.

Safkan B, Knuuttila M . Corticosteroid therapy and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 1984; 11: 515–522.

Krohn S . Effect of the administration of steroid hormones on the gingival tissues. J Periodontol 1958; 29: 300–306.

Waite I M, Saxton C A, Young A, Wagg B J, Corbett M . The periodontal status of subjects receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Periodontol Res 1981; 16: 100–108.

Feldman R S, Szeto B, Cauncey H H, Goldhaber P . Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the reduction of alveolar bone loss. J Clin Periodontol 1983; 10: 131–136.

Salvi G E, Lang N P . The effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (selective and non-selective) on the treatment of periodontal diseases. Curr Pharm Des 2005; 11: 1757–1169.

Preshaw P M, Lauffart B, Brown P, Zak E, Heasman P A . Effects of ketorolac tromethamine Mouthrinse (0.1%) on crevicular fluid prostaglandin E2 concentrations in untreated chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 69: 777–783.

Heasman P A, Benn D, Kelly P J, Seymour R A, Aitken D . The use of topical flurbiprofen as an adjunct to non-surgical management of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 1993; 20: 457–464.

Culshaw S, McInnes I B, Liew F Y . What can the periodontal community learn from the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis? J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38 Suppl.11: 106–113.

Garlet G P, Cardoso C R B, Campanelli A P et al. The dual role of p55 tumour necrosis factorα receptor in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-induced experimental periodontitis: host protection and tissue destruction. Clin Exp Immunol 2007; 147: 128–138.

Lima V, Vidal F D P, Rocha F A C, Brito G A C . Effects of tumour necrosis factorα inhibitors pentoxifylline and thalidomide on alveolar bone loss in short-term experimental periodontal disease in rats. J Periodontol 2004; 75: 162–168.

Graves D T, Delima A J, Assuma R, Amar S, Oates T, Cochran D . Interleukin1 and tumour necrosis factor antagonists inhibit the progression of inflammatory cell infiltration toward alveolar bone in experimental periodontitis. J Periodontol 1998; 69: 1419–1425.

Pers JO, Saraux A, Pierre R, Youinou P . Anti-TNF-α immunotherapy is associated with increased gingival inflammation without clinical attachment loss in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol 2008; 79: 1645–1651.

Smolen J S, Han C, Bala M, Maini R M et al. Evidence of radiographic benefit of treatment with infliximab plus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients who had no clinical improvement. A detailed sub analysis of data from the anti-tumour necrosis factor trial in rheumatoid arthritis with concomitant therapy study. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52: 10201030.

Mayar Y, Balbir-Gurman A, Machtei E E . Anti-tumour necrosis factorα therapy and periodontal parameters in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol 2009; 80: 1414–1420.

Mayar Y, Elimelech R, Balbir-Gurman A, Braun-Moscovici, Machtei E E . Periodontal condition of patients with autoimmune diseases and the effect of anti-tumour necrosis factorα therapy. J Periodontol 2013; 84: 136–142.

Seymour R A . Effects of medications on the periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000 2006; 40: 120–129.

Mascarenhas P, Gapski R, Al-Shammari, Wang HL . Influence of sex hormones on the periodontium. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30: 671–681.

Maier A W, Oban B . Gingivitis in pregnancy. Oral Surg 1949; 2: 334–373.

Plancak D, Vizner B, Jorgic-Srdjak K, Slaj M . Endocrinological status of patients with periodontal disease. Collegium Antrolpol 1998; 22: 51–55.

Figuero E, CarrillodeAlbornoz A, Martín C, Tobías A, Herrera D . Effect of pregnancy on gingival inflammation in systemically healthy women: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 40: 457–473.

Office for National Statistics. Contraception and sexual health 2008–2009. 2009.

Tilakaratne A, Soory M, Ranasinghe A W, Corea S M X, De Silva M . Effects of hormonal contraceptives on the periodontium, in a population of Sri Lankan women. J Clin Periodontol 2000; 27: 753–757.

Ficarra G, Beninati F, Rubino I et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in periodontal patients with a history of bisphosphonates treatment. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32: 1123–1128.

Lyles K W, Colón-Emeric C S, Magaziner J S et al. Zolendronic acid in reducing clinical fracture and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med 2007: 357; 1799–1809.

Reddy M S, Geisinger M L, Liu PR, Holmes C M, Vassilopoulos P J, Geurs N C . Intravenous bisphosphonates for osteoporosis and implant placement. Clin Adv Periodontics 2012; 2: 42–47.

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Oral health management of patients prescribed bisphosphonates. Dental Clinical Guidance, April 2011. Available at: http://www.sdcep.org.uk/index.aspx?o=3017 (accessed 30 September 2014).

Grant B, Amenedo C, Freeman K, Kraut R . Outcomes of placing dental implants in patients taking oral bisphosphonates: a review of 115 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 66: 223–230.

Jeffcoat M, Safety of oral bisphosphonates: controlled studies on alveolar bone. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2006; 21: 349–353.

Yip J K, Borrell L N, Cho SC, Francisco H, Tarnow D P . Association between oral bisphosphonate use and dental implant failure among middle-aged women. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 39: 408–414.

Lazarovici T S, Yahalom R, Taicher S, Schwartz-Arad D, Peleg O, Yarom N . Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68: 790–796.

Javad F, Almas K . Osseointegration of dental implants in patients undergoing bisphosphonate treatment: A literature review. J Periodontol 2010; 81: 479–484.

Goya J A, Paez H A, Mandalunis P M . Effect of topical administration of monosodium olpadronate on experimental periodontitis in rats. J Periodontol 2006; 77: 1–6.

Mitsuta T, Horiuchi H, Shinoda H . Effects of topical administration of clodronate on alveolar bone resorption in rats with experimental periodontitis. J Periodontol 2002; 73: 479–486.

Brunsvold M A, Chaves E S, Kornman K S, Aufdemorte T B, Wood R . Effects of a bisphosphonate on experimental periodontitis in monkeys. J Periodontol 1992; 63: 825–830.

Lee SJ, Oh TJ, Bae TS et al. Effect of bisphosphonates on anodized and heat-treated titanium surfaces: an animal experimental study. J Periodontol 2011; 82: 1035–1042.

Lane N, Armitage C G, Loomer P et al. Bisphosphonate therapy improves the outcome of conventional periodontal treatment: results of a 12-month, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 1113–1122.

Takaishi Y, Ikeo T, Miki T, Nishizawa Y, Morri H . Suppression of alveolar bone resorption by etidronate treatment for periodontal disease: 4 to 5 year follow-up of four patients. J Int Med Res 2003; 31: 575–584.

Takaishi Y . Treatment of periodontal disease, prevention and bisphosphonate. Clin Calcium 2003; 13: 173–176.

El-Shinnawi U M, El-Tantawy S I . The effect of alendronate sodium on alveolar bone loss in periodontitis (clinical trial). J Int Acad Periodontol 2003; 5: 5–10.

Graziani F, Cei S, Guerrero A et al. Lack of short-term adjunctive effect of systemic neridronate in non-surgical periodontal therapy of advanced generalized chronic periodontitis: an open-label randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2009; 36: 419–427.

Thomason J M, Seymour R A, Murphy P, Brigham K M, Jones P . Aspirin-induced post-gingivectomy haemorrhage: a timely reminder. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24: 136–138.

Elad S, Chackartchi T, Shapira L, Findler M . A critically severe gingival bleeding following non-surgical periodontal treatment in patients medicated with anti-platelet. J Clin Periodontol 2008: 35; 342–345.

Diener H C, Bogousslavsky J, Brass L M et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel gel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364: 331–337.

Coimbra L S, Steffens J P, Rossa Jr C, Graves D T, Spolidorio L C . Clopidogrel enhances periodontal repair in rats through decreased inflammation. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41: 295–302.

Coimbra L S, Rossa Jr C, Guimarȧes M R et al. Influence of anti-platelet drugs in the pathogenesis of experimental periodontitis and periodontal repair in rats. J Periodontol 2011; 82: 767–777.

Drouganis A, Hirsch R . Low-dose aspirin therapy and periodontal attachment loss in ex- and non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28: 38–45.

Horiuchi N, Maeda T . Statins and bone metabolism. Oral Dis 2006; 12: 85–101.

Saver B G, Hujoel P P, Cunha-Cruz J, Maupome G . Are statins associated with decreased tooth loss in chronic periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol 2007; 34: 214–219.

Lindy O, Suomalainen K, Makela M, Lindy S . Statin use is associated with fewer periodontal lesions: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2008; 8: 16.

Meisel P, Kroemer H K, Nauck M, Holtfreter B, Kocher T . Tooth loss, periodontitis, and statins in a population-based follow-up study. J Periodontol 2014; 85: e160–168.

Suresh S, Narayana S, Jayakumar P, Sudhakar U, Pramod V . Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effect of statins in chronic periodontitis. Indian J Pharmacol 2013; 45: 391–394.

Nassar C A, Battistetti G D, Nahsan F P et al. Evaluation of the effect of simvastatin on the progression of alveolar bone loss in experimental periodontitisan animal study. J Int Acad Periodontol 2014; 16: 2–7.

Jin J, Machado E R, Yu H et al. Simvastatin inhibits LPS-induced alveolar bone loss during metabolic syndrome. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 294–299.

Rao N S, Pradeep A R, Bajaj P, Kumari M, Naik S B . Simvastatin local drug delivery in smokers with chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Aust Dent J 2013; 58: 156–162.

Subramanian S, Emami H, Vucic E et al. High-dose atorvastatin reduces periodontal inflammation: a novel pleiotropic effect of statins. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 2382–2391.

Fajardo M E, Rocha M L, Sanchez-Marin F J, Espinosa-Chavez E J . Effect of atorvastatin on chronic periodontitis: a randomized pilot study. J Clin Periodontol 2010; 37: 1016–1022.

Epstein J B, Thariat J, Bensadoun R J et al. Oral complications of cancer and cancer therapy: from cancer treatment to survivorship. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62: 400–422.

Epstein J B, Stevenson-Moore P . Periodontal disease and periodontal management in patients with cancer. Oral Oncol 2001; 37: 613–619.

Hajishengallis E, Hajishengallis G . Neutrophil homeostasis and periodontal health in children and adults. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 231–237.

Taichman L S, Havens A M, Van Poznak C H . Potential implications of adjuvant endocrine therapy for the oral health of postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 137: 23–32.

MHRA Regulating Medicines and Medical Devices. Safety information. Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/index.htm (accessed September 2014).

Gurgan C A, Ozcan M, Karakus O et al. Periodontal status and post-transplantation complications following intensive periodontal treatment in patients underwent allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation conditioned with myeloablative regimen. Int J Dent Hyg 2013; 11: 84–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heasman, P., Hughes, F. Drugs, medications and periodontal disease. Br Dent J 217, 411–419 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.905

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.905

This article is cited by

-

Immunologic burden links periodontitis to acute coronary syndrome: levels of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in gingival granulation tissue

Clinical Oral Investigations (2024)

-

Age estimation from alveolar bone loss, re-evaluation of Ruquet’s method

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2023)

-

Is the use of contraceptives associated with periodontal diseases? A systematic review and meta-analyses

BMC Women's Health (2021)

-

Gene expression profiling on effect of aspirin on osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells

BDJ Open (2021)

-

Periodontal care in general practice: 20 important FAQs - Part two

BDJ Team (2020)