Think back to 2008. There was an inquest into Princess Diana’s death, Portsmouth won the FA Cup and Jonathan Ross and Russell Brand got in trouble for making a prank call to Andrew Sachs. Oh yeah, and the global economy almost collapsed.

To prevent the disintegration of international banking, and capitalism as we know it, governments were forced to pour trillions of dollars into rescue packages. In Britain alone, government loans to and investment in the banks amounted to hundreds of billions of pounds, which in turn presaged a debt crisis and years of austerity measures.

The world was in a dire mess and investment bankers, with their incomprehensible derivatives and collateralised debt obligations, were widely seen as the venal culprits. As deep recession took hold, almost everyone agreed the banks had become too powerful, the economy unbalanced, and that the executive pay and bonus culture in the finance industry was out of control. The common sentiment was that things could not carry on like this. Drastic change was needed.

Yet seven years on, the banks are once again returning massive profits and bonuses, the stock exchange is buoyant, consumer spending is driving growth, and the housing market is soaring ever upwards. The picture, however, is not quite so rosy at the bottom end of British society.

Back in 2008 the top 20% of households in the country were estimated to be worth 92 times more than the bottom 20%. The latest estimate puts the gap at more than 100 times. And a further £12bn of welfare cuts are planned by the new Conservative government. The gap between rich and poor is unquestionably widening.

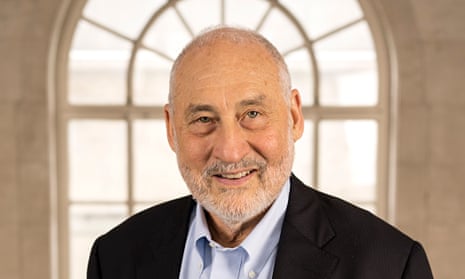

In other words an economic crisis that was created by the wealthy has had its most negative impact on the poor. This is the clear diagnosis that the Nobel laureate economist Joseph Stiglitz makes in his new book, The Great Divide. It collects a series of essays and articles that Stiglitz has written since December 2007, at which point he had already been predicting an economic implosion for three years.

The book is focused mostly, but not exclusively, on the US, where the crisis originated and where, like the UK, the chasm between the rich and poor has grown larger. It’s Stiglitz’s contention that this increasing distance between the top and bottom of the economic ladder is not just unseemly or immoral, but also counterproductive for the general health of the economy.

In which case, it’s reasonable to ask, why are we continuing down the same track that brought us to the edge of disaster? How is it that we have come to accept that giant multinationals are able to avoid paying tax, that banking and financial services can carry on as before with only minimal reform, and the only answer is austerity?

“Well,” says a smiling Stiglitz when I meet him at his publisher’s offices in central London, “those questions illustrate a theme of my book, which is that economic inequality leads to political inequality.”

No doubt it does, but the point is that while almost everyone thought in 2008 that it was time for government to impose its will on huge, unaccountable enterprises driven only by short-term profits, the general election we’ve just had was fought on the understanding that no one should say or do anything that frightened big business. We may still be living through the economic consequences of 2008, but the political moment appears to have long passed.

Stiglitz agrees. With his grey beard and intense yet playful expression, he looks like Richard Dreyfuss’s older and more cerebral brother. If you think of Dreyfuss’s half-horrified, half-amused take on the insularity of the townspeople in Jaws, it gives you some idea of Stiglitz’s feelings about the political and economic elites.

“One other element you can’t ignore is the quality of political leadership,” he says. “I do think that if we’d had a Franklin Roosevelt, it would have turned the tide in an important way.”

Like many on the American left, Stiglitz is disappointed with President Obama. “He was captured by the bankers,” he complains, “by the whole coterie of people like [Larry] Summers and [Timothy] Geithner, the architects of financial deregulation. No responsible person would hire for their major advisers on [how to save something] the people who destroyed it.”

Nor does he think Ed Miliband, who has been criticised for an anti-business campaign, had the required vision. “There were some good things, but his was a minimalist agenda that was out of sync with the magnitude of the problems.”

His argument is that, contrary to the Cameron-Osborne line, the UK economy is not doing well. “The GDP per capita in the UK is lower than it was before the crisis. That is not a success. The crisis, remember, is seven years ago. You will have essentially had a lost decade of zero growth.”

He is equally scornful of the notion that the UK economy is at least in a better shape than many of its competitors. “Productivity is really performing poorly. Median income – income in the middle – is stagnating. If you were grading the UK’s economic performance you would have to give it a low grade. If you look at your neighbours, the reason the eurozone is doing so badly is the euro. You made one good decision some years ago, not to join the euro. You can’t give Cameron credit for that.”

To the extent that the coalition succeeded in stimulating the economy, Stiglitz puts it down to Cameron’s backtracking and going easy on the cuts he threatened. “And I think the real fear now is, untethered, he may go back to austerity, and then we’ll get another experiment.”

He pronounces the word “experiment” in the same sceptical tone one might employ to describe the medical research of Dr Frankenstein.

“The crisis began in the United States and we are having a more robust recovery. I don’t think we’ve done a great job, but we did not have as much austerity.”

Listening to Stiglitz one-to-one, like reading him, is an invigorating experience. “Yes,” you nod your head and think, “we have to be more ambitious and yet coolly rational about these things.” At which point you scratch your head: why are all politicians so timid and fearful of upsetting the false gods of the financial markets?

Then you think of poor François Hollande, who came to power in France promising massive reform and redistribution of wealth, and promptly witnessed the flight of capital and talent, a rise in unemployment, and the precipitous decline of his popularity that was only reversed by the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

Stiglitz has himself attacked Hollande’s approach, accusing him of cutting taxes and lowering government spending. So Hollande has “disappointed” him, too.

And it has to be said, in spite of his warm, approachable manner, Stiglitz appears to be a man who’s very often disappointed by those he encounters. He comes directly to our meeting from the BBC, where he was on Start the Week. Another guest was Steve Hilton, former adviser to David Cameron, who has written a book arguing that government and corporations have become alienating because they are too big and lack human scale. It was obvious, even across the radio waves, that Stiglitz was underwhelmed by Hilton.

“He was just a bundle of platitudes,” says Stiglitz. “It was a little painful having to be there. And the guy who ran the programme [Andrew Marr] did not do a good job this time. He seemed to be taken up with these platitudes. How are you going to solve big problems? Devolution? Watch the iniquities that occur at the local level where you have powerful elites.”

But then if you’re a professor at Columbia University, have been chief economist at the World Bank and have won the Nobel prize for economics for jointly laying the foundations for “the theory of markets with asymmetric information” you are likely to find many people a little lacking in the thinking department.

In 2002 Kenneth Rogoff, then director of research at the IMF, wrote an open letter to Stiglitz in which he took him to task for his superiority towards others – he apparently dismissed IMF staff as “third rate” – and lack of humility about himself. Writing of Stiglitz’s book Globalisation and Its Discontents, Rogoff noted: “I failed to detect a single instance where you, Joe Stiglitz, admit to having been even slightly wrong about a major real world problem.”

I mention the letter and ask him, can you remember the last time you were wrong?

He breaks into a loud laugh.

“I have to say the one thing that he [Rogoff] was most wrong about was when he said no serious economist would support capital controls or interventions. Even his own institution now agrees with me.”

In other words Stiglitz was once again on the correct side of the argument. Is that always the case?

“I thought Obama was going to be more forceful. I supported his anti-Iraq war position. I thought that he would be able to get us out of Guantánamo, that he would effectively address the problems of the banks. That’s an example of a very bad judgment.”

But that’s about character, I say, or politics, not about economics per se. In his own discipline, does he acknowledge his predictive errors?

He thinks for a while, as if rifling through his memory banks.

“I do think broadly my outlook has been vindicated, but economic models are as complicated as weather models. You can be basically right and yet in the relatively short run be wrong.”

One example, he says, was when he predicted that the housing bubble was going to burst in 2005. But he failed to take fully into account the effect of China buying American bonds and therefore suppressing long-term interest rates.

“So the timing of the breaking of the bubble was a little bit wrong,” he says, before quickly adding: “But in terms of there being a bubble and it would break, I was right.”

Indeed he was. It’s on this major piece of analytical prescience that much of Stiglitz’s renown rests. After all there are plenty of Nobel-prize winning economists no one has ever heard of. George Akerlof, for example, and Michael Spence, the two economists with whom he shared his Nobel prize. But it was his campaigning journalism for Vanity Fair and the New York Times, in which he mapped out inequality, regulatory failings, market iniquities and the structural reasons for the crisis, that really made his name.

Perhaps the most notable of these was a piece that appeared in Vanity Fair under the title, supplied by editor Graydon Carter, “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%”, that played on Abraham Lincoln’s famous appeal in the Gettysburg Address for “a government of the people”. The slogan of the Occupy Wall St movement became “We are the 99%”.

I asked a highly regarded macroeconomist in New York (who preferred not to be named for professional reasons) what other economists thought of Stiglitz. “He’s absolutely brilliant,” he said, “with a very creative mind. He fully deserved his Nobel prize, but like [Paul] Krugman he’s increasingly inclined to pontificate beyond his knowledge or experience. He’s a great theorist, and his work on inequality is respected, but he’s not someone you’d ever go to for policy advice.”

However, it’s said that Hillary Clinton, many people’s favourite to be the next US president, is doing exactly that. A couple of weeks ago Stiglitz and several other economists published a report called “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity”, which was aimed directly at Clinton.

Along with Krugman and Thomas Piketty, Stiglitz forms a triumvirate of leading economic critics of global capitalism, 21st century-style. But he is not, he insists, anti-capitalist. Whereas Piketty believes that extreme inequality is inherent to capitalism, Stiglitz argues that it’s a function of faulty rules and regulation. And, in case there was any doubt, he’s certainly no Marxist. While he admires Marx’s critiques of exploitation and imperialism, he has little time for his analysis of economics.

Instead the macroeconomist he most admires is John Maynard Keynes, the Bloomsbury intellectual and sometime director of the Bank of England, who argued that state intervention was vital to combat the boom and bust cycles of capitalism. In particular Keynes made the case that nations should save when the economy is strong and spend when it is weak. In many ways, Stiglitz’s positions, which are essentially Keynesian, would have been viewed as fairly conventional in the pre-Thatcher and pre-Reagan era.

“My argument is that these guys – the bankers and monopoly corporations – have destroyed capitalism in some sense,” he says. “There are certain rules which are required to make a market economy work. And these guys are really undermining these rules. My book is really about trying to get markets to act like markets. That’s hardly radical, at one level. But at another level it is radical because the corporations don’t want markets to look like markets.”

In spite of an audience with George Osborne later on in the day we met, Stiglitz was carrying a message that many in the business world do not want to hear. There was an instructive exchange of views that evening with the restaurant entrepreneur Luke Johnson on Channel 4 News in which the two men painted diametrically opposed portraits of the British economy.

Johnson spoke of growth, prudence, new jobs and higher wages, while Stiglitz countered with falling real incomes and productivity. Across Europe, he said, austerity had accounted for the loss of “trillions of dollars”. He is convinced that if Germany continues to drive the policy of austerity the eurozone will collapse.

These are massive questions with monumental consequences, but they’re not the kind to capture the public imagination, at least not in Britain. There seems to be a shared belief, born perhaps of apathy, that we can somehow turn away from what’s happening across the Channel, tighten our belts and work our way out of trouble. So to that extent, Stiglitz may find that he’s preaching to the deaf.

But his central complaint about inequality does register here. Sometimes it seems as if you can almost physically see the two poles of Britain moving further apart on a daily basis. And not just Scotland and England.

Nevertheless, capitalism cannot work without the incentive basis of inequality. To get ahead, there has to be someone left behind. At what point does inequality stop being motivational and become dysfunctional?

“You need some inequality but it’s very clear the extremes and manner of inequality are counterproductive. Take CEO pay in the US, which is 300 times the average wage of the workers. It used to be 20 times. Now I’m not going to say it should be 25 or 40 times, but if we got it down to a hundred times that would certainly be a step in the right direction. And I don’t see that happening.”

We’re told, when questions are asked, that concerning ourselves with executive pay is simply the politics of envy. Why should it matter how much bosses earn if their shareholders are happy to pay and profits are returned?

“Because it’s actually destructive of the long-term performance of the economy. Not only does it create more inequality but we’re paying the CEO money that could have been invested in the firm. It’s also the way they get compensated through stock options, which gets them to focus on the short-term of the next quarterly return. So that’s a mechanism that enervates and distorts the economy, because you don’t invest in machines or long‑term projects.”

This makes close to irrefutable sense, at least to me, but economics, as Stiglitz says, is a complicated business and the “dismal science”. I ask him what he thinks of the Greens, who seemed to stand on an anti-growth manifesto in the election. Surely as someone who talks of growth all the time, he must oppose this brand of radicalism. But no.

“I think the Greens are right,” he says. “We have to make sure that the benefits of growth are shared more equally. Anybody who is concerned about our environment has to be committed to a more egalitarian policy, because we can’t let those at the bottom have inadequate means.”

Yet surely it’s the drive to attain those adequate means in China, India and elsewhere in the emerging markets that presents such a daunting environmental challenge.

“We’re not pricing carbon,” he says. “We’re not pricing our resources, that again goes back to a distorted economy. We have an innovation system that has the peculiar characteristic that it’s figuring out ways to replace labour, when we already have high unemployment, but not ways to save our planet.”

That must mean that some machines are not good to invest in – the ones that replace labour, which is not a bad working definition of a machine.

As well as supporting the Greens, Stiglitz has been a vocal enthusiast for the SNP. He told Andrew Marr that he admired their policies on education, particularly free university education.

I make the case that tuition fees are actually progressive, a means of addressing inequality, because only the wealthy pay – those who go to university and earn enough money to repay the loans. Whereas you have to tax the poor and the non-university students if further education is free for all. “I think there’s some truth in that,” he agrees, though suggests there’s a psychological reluctance to take on debt, however notional, among the less well-off. His key point, though, is that Britain can afford universal free further education. “Obviously if you don’t want to raise taxes, you can’t afford it, but these are investments in people with high returns.”

As for house prices, they too will at some point encounter a sharp dose of economic reality. What has delayed that moment of reckoning has been a lack of house-building. “So there’s a real supply-side story in the UK. But the more general problem, which is true in the US, is to realise that our financial system before the crisis fed a real estate credit bubble, and it is maybe doing that again.”

Another crisis looms, then?

Yes, says Stiglitz: the quantitative easing – the injection of money – that has been a major monetary policy in both the US and the UK has bypassed many of the businesses it was intended to help, and instead gone into assets: the stock market and real estate. Which of course only increases inequality.

It’s not a situation that can last, says Stiglitz, but the weakness of the global economy should keep anything dramatic from happening for the next year or two.

I’m still trying to work out if that’s good news when a couple of days later I go along to the Royal Geographical Society to hear Stiglitz speak. It’s a sold-out event and there’s a palpable air of anticipation in the hall. He opens by acknowledging that the subject of inequality has “punched through” as an issue in recent years, and then ruefully jokes: “I wish this manifestation of interest had been shown [on election day].”

As a public intellectual, alas, Stiglitz is not a great public speaker. He covers a lot of ground but he wanders, loses his thread, and doesn’t really hammer home his argument. There are plenty of graphs and data and information, most of it concerning the US, and it’s damning stuff. But what there isn’t is a compelling vision of how to put things right.

In a sense this is where Miliband came unstuck. He could point his finger at the symptoms of inequality – the food banks and the bloated bankers – but what he couldn’t do is show a convincing way of improving the situation.

But it is there. It just needs someone to take Stiglitz’s basic finding that inequality, quite apart from being bad for the poor, is bad for growth, and then convey it to the public at large in a manner that speaks to people’s conscience and aspiration. Whoever is left in the running for the Labour party leadership should get reading.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion