Writing Is the Process of Abandoning the Familiar

The novelist and editor Anna North discusses the Odyssey’s timeless lesson about leaving the comforts of home.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

When I spoke to Anna North, the author of The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, she pointed out that the Odyssey doesn’t really end with its hero’s dramatic, suitor-slaying return. In Book 11, while in the underworld, the dead seer Tiresias orders Odysseus to take one last trip before settling down. If he wants to appease the gods, Odysseus must take his oar and journey as far inland as he can. When people start to gawk, with no recognition, at the strange tool on his back, he’s travelled far enough.

In our conversation for this series, we discussed what North called “the oar moment”: the sudden, profound realization that you’ve gone too far from home. She explained, too, how writing a novel is a bit like taking advice from Tiresias—undertaking a long journey with no clear destination, for reasons you don’t fully understand.

The Life and Death of Sophie Stark takes the form of a fictional oral history, one that explores the way cultural myths are made. The title character, a pioneering film director, never speaks to us directly: We learn about her only through a chorus of competing voices, plus a handful of journalistic reviews. We’re asked to consider a flawed cultural hero whose greatness stems from the fact that she can’t separate people from actors, life from art—and whose reputation rests on the biased narratives of people she inspired, manipulated and hurt.

Anna North is a staff editor at The New York Times. Her first novel was America Pacifica, and her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in The Atlantic, Salon, and The San Francisco Chronicle. She lives in Brooklyn and spoke to me by phone.

Anna North: My grandfather first recommended the Odyssey to me. When he died a few years ago, I went looking for my original copy because I wanted to read from it at the funeral. I found it in my parents’ house, with the original receipt still inside. So I could date exactly when I first got the book: I was eleven years old.

I have strong memories of reading it for the first time. The Odyssey’s a great book for kids. A lot happens. There’s strangeness, magic, excitement. Of course, the names are very weird to a modern person, and I remember getting tripped up over that. But still, I loved it.

It’s an obsession that’s stayed with me into adult life. I’ve always been interested in Greek and Latin literature. I’m excited by the ways those traditions show how old our concerns are. If you read Livy, for instance, you find that almost everything that’s said in American politics had probably said by the Romans, too: everything from concerns about men not being manly enough anymore to debates about the kinds of things the founding fathers cared about. With the Odyssey, it’s possible to see how many of the stories we still tell exist in ancient texts—they’re archetypal. There are things that human beings like to talk about, and always have, and a quest is one of them.

For me, the Odyssey is more appealing than the Iliad and other war narratives. Compared to the Iliad, which may be more widely read, I think of the Odyssey as a book that’s much more feminist. There are almost no women in the Iliad at all, because it’s about a war in which basically no women were allowed to fight. The Odyssey, by contrast, has female characters, and they’re much more interesting. They’re ancient Greek, so they’re not generally in positions of power, and yet some of them are very powerful. They are witches. They can turn you into a pig—things like that. There’s lots of interesting thinking, too, on the ways in which Odysseus himself might be feminine or embody feminine qualities. As a character, his whole thing is less about his prowess and battle and more about his wits. The first line talks about how he’s a man of twists and turns, which is one of his epithets—and though it’s stereotypical to say that a woman couldn’t be good at war, and would only be good at twists and turns, it does feel like he has a gender-bending aspect as a character.

Obviously, the Odyssey is a hero-quest story, and that’s one reason I became so fixated on it. I’m really interested in how someone becomes a hero or an icon. In what ways do you have to give up part of your humanity, your human life, when you’re a hero? Odysseus obviously gives up a huge chunk of his life—time with his family, his ability to do normal things. But, by contrast, what does he gain? What are the ways that you become larger than life when you’re a hero? In what ways can you become superhuman?

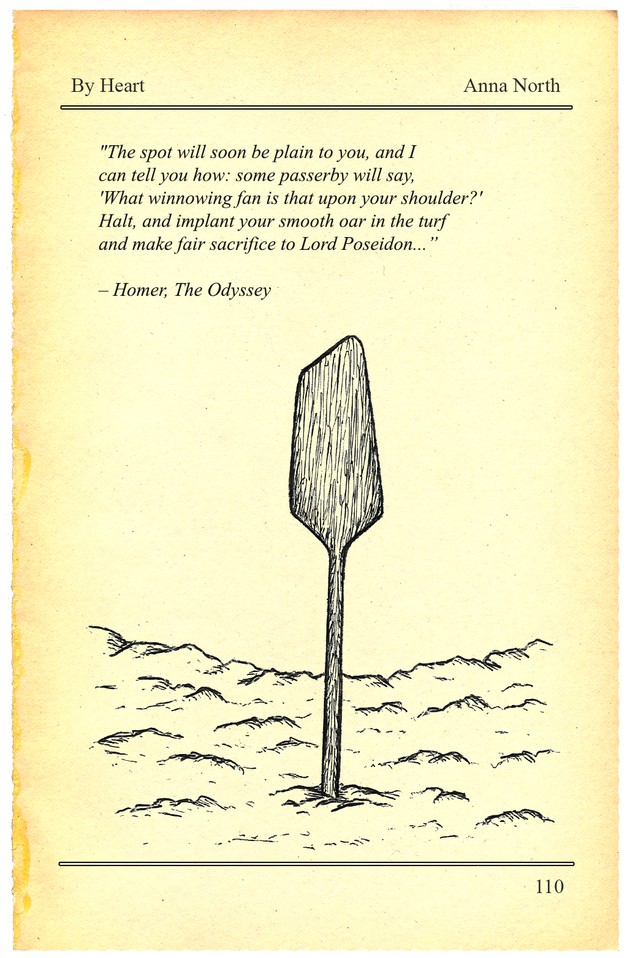

For a long time, I’ve been obsessed with this particular part of the Odyssey where Tiresias, the seer, explains to Odysseus what he has to do before he can really go home for good. The whole drama of the book has been Odysseus’ getting home to Penelope and all her suitors. You’d think he’d be done after he returns, kills all those men, and reclaims his family. Instead, Tiresias tells him that he has to do one more thing:

But after you have dealt out death—in open

combat or by stealth—to all the suitors,

go overland on foot, and take an oar,

until one day you come where men have lived

with meat unsalted, never known the sea

nor seen seagoing ships, with crimson bows

and oars that fledge light hulls for dipping flight.

The spot will soon be plain to you, and I

can tell you how: some passerby will say,

'What winnowing fan is that upon your shoulder?'

Halt, and implant your smooth oar in the turf

and make fair sacrifice to Lord Poseidon:

a ram, a bull, a great buck boar: turn back,

and carry out pure hekatombs at home

to all wide heaven's lords, the undying gods,

to each in order. Then a seaborne death

soft as this hand of mist will come upon you

when you are wearied out with rich old age,

your country folk in blessed peace around you.

And all this shall be just as I foretell.

Tiresias instructs Odysseus that, before he can go home, he must take his oar and walk inland until someone mistakes it for a winnowing fan—a tool for winnowing grain—and asks him what it is. In other words, as soon as he’s gone to a place where people don’t know what an oar is, then he’s gone far enough. If he plants the oar in the earth, and makes an offering there, then he can go home. But he has to make this symbolic gesture of going so far away that his oar—the thing he’s based his life on—becomes unrecognizable. Only then can he return home safely.

As advice, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. There are a lot of instructions like this in the Odyssey: strange, inexplicable things you must do to avoid incurring the wrath of gods. But there’s a way of thinking about this particular passage that does make sense to me: If the point of this book is to go on a journey, then to finish it you have to go away as far as possible before you can truly return and be done.

In a funny way, this takes Odysseus down a peg. He’s a known hero to the Greeks, and he’s been the hero of this story. I love the idea that, before he can go home, he has to go to this place where he’s totally humbled. Not only do they not know who he is, they don’t even know what his oar is. He’s meaningless to them—and that’s an interesting thing to force him to do.

I think a lot about home and away, and that’s one reason this passage feels resonant to me. I’ve felt very conflicted about where my home is ever since I left Los Angeles, which is where I’m from. In all the places where I’ve lived, I’ve asked myself: Am I home now? It’s a hard question for me to answer. But I like having this passage, which helps me define what not home is. This is how you know when you’re really not home—when something precious to you becomes unrecognizable to everyone else—and that feels helpful to me.

An example is when I moved to New York after getting my MFA in Iowa City. I’d lived here not that long—maybe a month. And one day I walked into this coffee shop wearing these bright green pants. The guy behind the counter said, “Nice pants! Where did you get those?”

I told him I got them in Iowa City. He was like, “Where’s that?”

And I said, “Um, it’s in eastern Iowa.”

“Oh,” he said, “I thought it was a store.”

That was the oar moment.

But there’s an opposite of that type of moment, too: If you’re far from home, but then you meet someone from your home, or see something you also have at home, and you have this enormous sense of recognition.

Another aspect of this comes up for me related to the fact that Odysseus basically has to do something for no reason. There’s no clear reason why he should to take this long journey Tiresias asks him to go on, and that’s a lot like writing. Writing is this strange impulse, not a very practical impulse, and it doesn’t make sense to everyone. But for some reason—if you have the impulse—you have to do it anyway. You have to go on this long journey and do something that’s really hard, and all of it for no real reason. I don’t entirely mean that. I love reading, and I think books are so important, and both writing and reading give me a lot of pleasure. I think they have real meaning. And yet, it’s not like you’ve built something when you write a novel. You’re not producing anything physical. You’re putting symbols together. Just the way that what Odysseus is asked to do is symbolic—planting his oar in the ground is a symbolic gesture.

On different level, though, Odysseus’s act has actual meaning: Presumably, the gods would be angry if he didn’t do it. There could be real-life consequences if he fails to perform this action. Similarly, if you’re someone who really loves writing, it can be really hard if you don’t listen to that impulse. There could be real-life consequences, at least in terms of you feeling sad.

It might sound cheesy, but I think writing is a kind of a journey. For me, especially if I’m working on a novel, it takes at least a year of fumbling around before I really get anywhere. As you try to imagine yourself into this world, it’s a process of writing stuff, throwing it out, writing, throwing it out. You’re trying to create this place for yourself inside your head; it’s very hard to get to that place, and it takes a long time to get there. But then, finally, there is the sense that maybe you’ve arrived, though you’ve had to discard a ton of stuff along the way.

Sometimes I wish someone could tell me: Just go to this specific place, and then you’ll be there. I think that’s why I like that passage so much. It’s almost a fantasy to imagine that someone would tell exactly how to get somewhere creatively, and you could just go there, and then you would know. “The spot will become plain to you,” Tiresias says. And yet it’s true with writing that, every now and then, you do get a feeling of total rightness. Suddenly, you can say: Yes, now I’m in the right place with this piece of work. That’s when you can plant your oar in the turf.

That feeling is the only thing I can use as a guide for when things are going well. There’s so much wandering. But every now and then you have this clarity, and—ding!—the sudden sense that things are where they’re supposed to be.