Long-term study shows why bullying is a public health problem

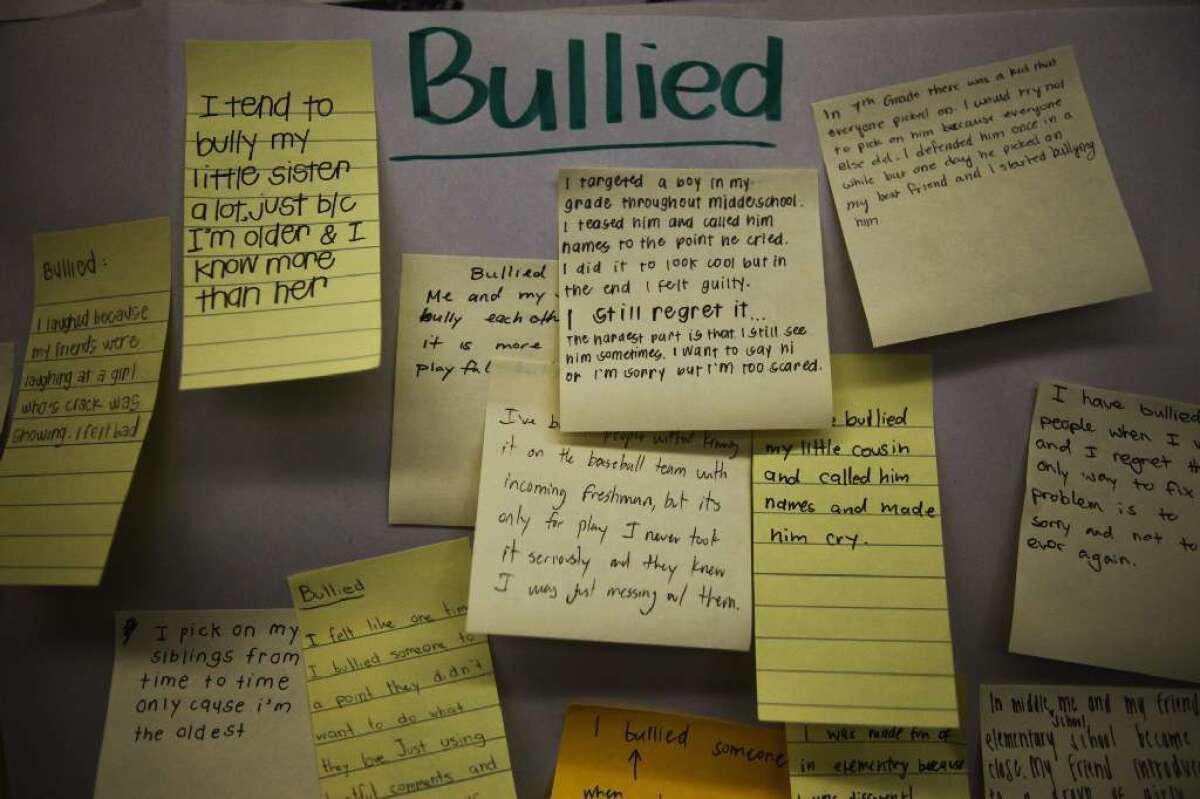

Teens who were bullied at age 13 were more likely to be depressed as adults, according to a new study. The findings suggest that curbing bullying in schools will improve public health years later. Above, high school students write notes acknowledging their own bullying behavior.

Bullying may be responsible for nearly 30% of cases of depression among adults, a new study suggests.

By tracking 2,668 people from early childhood through adulthood, researchers found that 13-year-olds who were frequent targets of bullies were three times more likely than their non-victimized peers to be depressed as adults.

Even when the researchers accounted for factors like a teen’s record of behavioral problems, social class, child abuse and family history of depression, those who were bullied at least once a week were more than twice as likely to be depressed when they grew up.

The findings, published Tuesday in the BMJ, should prompt parents, teachers and public health authorities to get serious about cracking down on bullying, the study authors wrote.

“Depression is a major public health problem worldwide, with high social and economic costs,” they wrote. “Interventions during adolescence could help to reduce the burden or depression later in life.”

Previous studies that examined the link between bullying and depression have determined that the two are related. For instance, adults who are depressed are more likely to recall being bullied as kids. But perhaps adults without depression were bullied as well but have put the abuse out of their minds.

To get around that problem, a group of researchers from four universities in England turned to data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Some of the study participants were recruited into the study before they were even born; others joined when they were about 7 years old. The administrators kept track of all kinds of information about the kids and their families, and they asked questions about bullying multiple times between the ages of 8 and 13.

For this study, the researchers focused on peer victimization at age 13. At the time, the teens were asked about nine types of bullying and whether they experienced them “frequently” (at least once a week), “repeatedly” (at least four times altogether), “sometimes” (less than four times) or not at all.

Name-calling was the most common type of bullying, with 36% of teens saying they had been on the receiving end of this behavior (including 9% who were victimized frequently). And 22% of the kids said bullies had taken their stuff. Beyond that, 16% of the teens said bullies had spread lies about them; 11% said they had been hit or beaten up; 10% were shunned by their peers; 9% said they had been blackmailed; 8% said bullies tried to get them to do something they didn’t want to do; 8% said they had been tricked; and 5% said bullies had spoiled a game to upset them.

Most of this bullying was never reported to teachers, and the 13-year-olds didn’t even tell their families about one-third of the time.

Not only did the researchers confirm that victims of bullying were at greater risk for depression as adults, they also found a dose-response relationship between the two. In other words, the more bullying that a 13-year-old had to endure, the greater the odds that he or she would be depressed years later.

Among teens who said they weren’t bullied at all, 5% went on to suffer depression. But among the teens who were frequent victims, 15% were depressed as adults. What’s more, 10% of the frequent bully victims had been depressed for more than two years, compared with 4% of their counterparts who weren’t bullied at all.

The results offer support for the idea that bullying during childhood leads to depression in adulthood, but they don’t prove that one causes the other. Nailing that down would require an experiment that randomly assigned some people to be bullied and others to be left alone. But the results imply that “approximately 29% of the burden or depression at age 18 years could be attributed to peer victimization,” the study authors wrote.

“These findings lead us to conclude that peer victimization during adolescence may contribute significantly to the overall public health burden of clinical depression,” they wrote.

In an editorial that accompanied the study, University of Cambridge bullying prevention expert Maria Ttofi wrote that the study results should prompt school authorities and health officials to think seriously about ways to stop bullying by teens. If they do, they will reap the benefits for years.

“Effective antibullying programs can be seen as a form of public health promotion,” she wrote.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.