Following the U.S. Civil War, Secretary of State William Seward lobbied President Andrew Johnson to partake in the Paris Expo of 1867. Seward emphasized that it was in the country’s best economic interest to do so. Moreover, participation would reaffirm the country’s unity and ideals, important considerations as nationalism and the push for greater democracy marked the Western world.

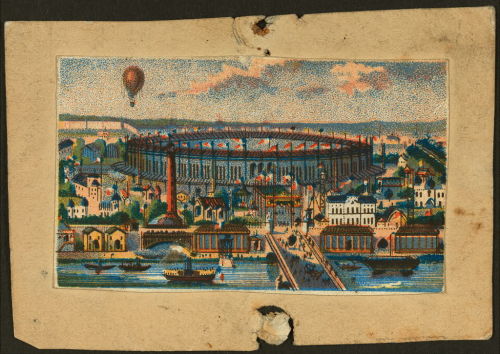

View of the Paris Exposition of 1867 showing waterfront, main exhibit building, and balloon flying in the distance.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

The Universal Exposition of 1867 was held against the backdrop of a changing European landscape. Throughout the exposition’s tenure, April through November, U.S. Minister to France John Adams Dix reported to Washington about unrest in Central Europe as the Italian and German unification movements gained momentum. Dix also reported on the assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II in the Bois de Boulogne that June: like many European monarchs, the Russian Emperor attended the exhibition while in Paris.

U.S. involvement not only served to demonstrate the Union’s desire for post-war stability, it also provided new opportunities for American food vendors: the production and sale of food for on-site consumption. According to the Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, introduction of “café restaurants as an element of international competition” at that year’s event was “a happy thought.”[1] Boston firm Dows & Guild ran a bar and restaurant which introduced American-style cocktails (noggs, smashes, and eye openers) and dishes (green corn, stewed oysters, and soft shell crabs) to the international public.

Some were disappointed. As honorary U.S. Commissioner W. E. Johnston wrote, “we had anticipated being called upon to taste horse, dog, and bear, swallows’ nests, sharks’ fins, fish-worms, grasshoppers, and sea-lions.”[2] But the American restaurant had an overwhelming success: its cream sodas, manufactured and sold in Europe for the first time. This unique “American specialty” was popular with the everyday fairgoer as well as with the royalty of Europe, who “often partook of the delicious draught.” Perhaps Dix and other members of the U.S. Legation in Paris also imbibed the bubbly delight.[3]

Source: [1-2] W.E. Johnston, “Report on the Preparation of Food: Café Restaurants,” Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, 1867, Vol. 5, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1870), pages 5-6; [3] James M. Usher, Paris Universal Exposition 1867, With a Full Description of Awards Rendered to the United States Department and Notes Upon the Same, (Boston: National Office, 1868), 75.

fordlibrarymuseum liked this

photographywarehouse liked this

photographywarehouse liked this historyatstate posted this