Scientists Recover the Sounds of 19th-Century Music and Laughter From the Oldest Playable American Recording

Computer analysis of a piece of foil reveals audio captured by a Thomas Edison-invented phonograph in St. Louis in 1878.

Last night at the GE Theatre in Schenectady, New York, an audience of about 200 people sat and heard the sounds of a someone playing the cornet, a man laughing, and a recitation of "Mary Had a Little Lamb" and "Old Mother Hubbard." It is believed that this event was the first time that any public audience had heard those sounds since they were captured by a Thomas Edison-invented phonograph in St. Louis in 1878.

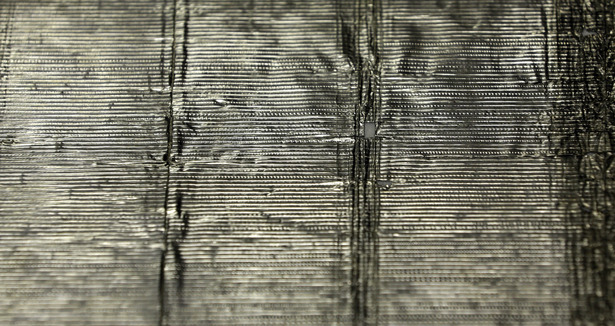

For years the audio was trapped on the piece of foil you see above. There was no device that could play it and even if there had been, doing so would have likely ruined it. This summer, at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California, physicist Carl Haber and his team were able to create a 3D picture of the foil whose topography could then be translated into sound using techniques of mathematical analysis and physical modeling to calculate how a needle would have played the recording. They were able to do so "without physically having to touch them," he explained to me. "And that's kind of the key issue, because these things are so old and fragile and torn-up, broken, and delicate that in many cases it just would not be possible to play them back in any of the more standard ways."

Once they had the scan and had processed it, here's what they heard:

They cleaned it up a bit, and got this:

"It doesn't matter anymore that you don't have the exact machine that was used," Haber said to me. "Our technology, since it's based upon modeling and simulation, it can accommodate anything really, any kind of mechanical recording. That's why we've been able to fill in the picture so completely."

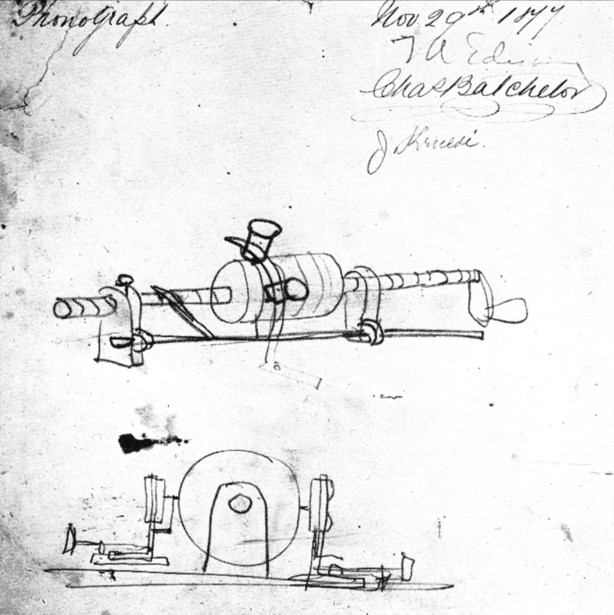

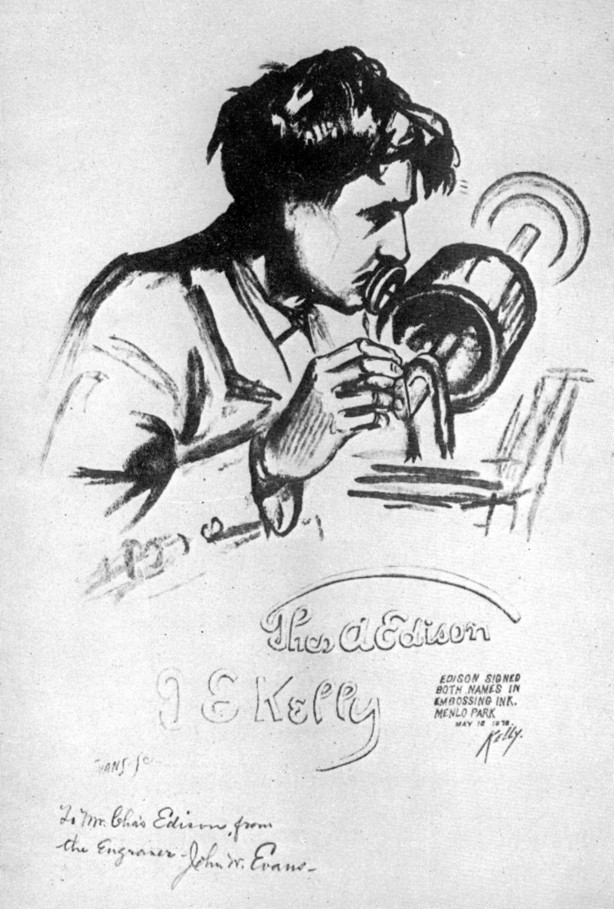

Edison invented his tinfoil phonograph in 1877 and began selling it in 1878. "This is the oldest recording in the United States and anywhere in the world that was made as a reproducible recording that's ever been played [in modern times]," Haber said. "This was very, very close to the moment of Edison's invention -- just a few months after Edison's invention." Earlier phonautograms from France are playable today (also recovered by the Berkeley Lab), but they were not intended to ever be played back.

The recording, from a demonstration on June 22 of 1878, is not believed to contain Edison's voice (he was hard of hearing and had very distinct pronunciation). Museum trustee John Schneiter told me that curator Chris Hunter believes the voice belongs to St. Louis newspaper political humor writer, Thomas Mason, who went by the pen name I.X. Peck -- "I expect." (Edison's first recording, which he claimed was a recitation of "Mary Had a Little Lamb," no longer exists, or, if it does, no one knows where it is.)

"This is the first, this is oldest," Haber explained. "Edison was the first to reproduce sound. And this is the oldest Edison that has so far been played. There may be some other foils around -- there are some other foils around at the Smithsonian or Edison sites -- and they might be a little bit older or not, but they're basically from that same few-month period after the invention, but they have not been played [since they were made]."

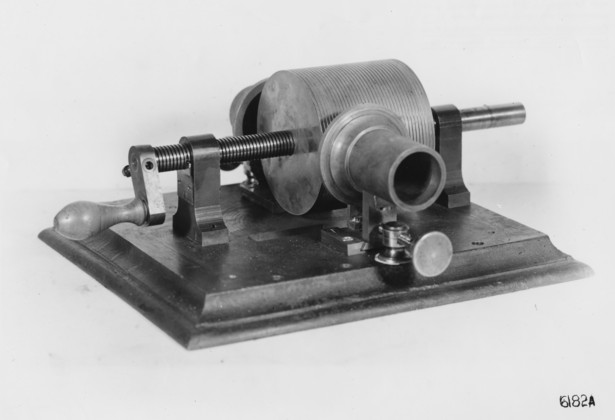

The recording was made by a phonograph like the one above, whose stylus would move up and down, recording the sound waves as a hand crank rotated the cylinder. After a few playbacks, the stylus would rip through the foil, and demonstrators had a practice of tearing up the recording and handing out the scraps as souvenirs. Pops and scratches heard in the recording were likely created by the way the foil was folded while it was in storage for more than a century. A woman whose father had been an antiques dealer in the midwest donated the foil to the museum in 1978.

These early recordings are the earliest instances of a technology that has shaped just about every aspect of life. Recorded sound gave rise to the music industry, of course, but that's just the half of it; ethnographic research, field recording, journalistic interviews, historical research -- all of these capabilities trace back to Edison, his foils, and, later, his wax cylinders. With his invention in 1877, Haber said, "Edison really transformed the world."

Here, for your listening pleasure, is the 78-second recording, broken down into more manageable bits: