/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/37425382/164850157.0.0.jpg)

In the wake of the police-involved deaths of black men including Michael Brown and Eric Garner last year, thousands have protested across America to turn our collective attention to the different treatment of black and white people at the hands of America's criminal justice system.

The focus, of course, is much needed. But there's discrimination in many other places, too. Every single day, there are many more race-related deaths that result from a quieter problem: systemic discrimination in the US health system.

The truth is this: even today, in America, white privilege works better than most medicine when it comes to staying healthy. Racial health disparities may be a more subtle killer than gun violence or murder, but they're arguably a more violent one. They infect every part of the body, and they strike at literally every stage of life, from cradle to grave.

Baltimore or Ferguson — the site of recent riots — have life expectancies and infectious diseases rates that hover near those of the developing world. These cities can be seen as microcosms of a much larger problem. "If the statistics that are present in these communities were present in any white community in Baltimore," Douglas Miles, a Baltimore pastor, told the New York Times, "it would be declared a state of emergency."

The gap starts with birth

Simply put, black babies don't have a fair start. Pre-term delivery — coming into the world at less than 37 weeks — is one of the key causes of infant death in the US. These early births lead to a host of health complications, both short and long term, from vision and hearing impairment to cerebral palsy. Black women have a 43 percent higher risk than white women for delivering their babies prematurely. They are also between two and three times as likely to have babies dangerously early, in less than 32 weeks.

When it comes to nursing, black mothers are consistently less likely to breastfeed than white mothers, despite the guidelines suggesting all mothers do so because of well-documented health benefits. This gap has been explained by everything from preference to a lack of access and education about health benefits to a dearth of support for new moms. The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that hospitals in predominantly black neighborhoods also do less to promote breastfeeding than mostly white hospitals.

The black-white health divide continues throughout life

In childhood, black kids are more likely to suffer asthma and obesity. They have poorer oral health than white people. The health problems trickle into adulthood, when diabetes strikes black people much more often than it does white people: in 2010, the prevalence of obesity in black people was nearly twice that of white people.

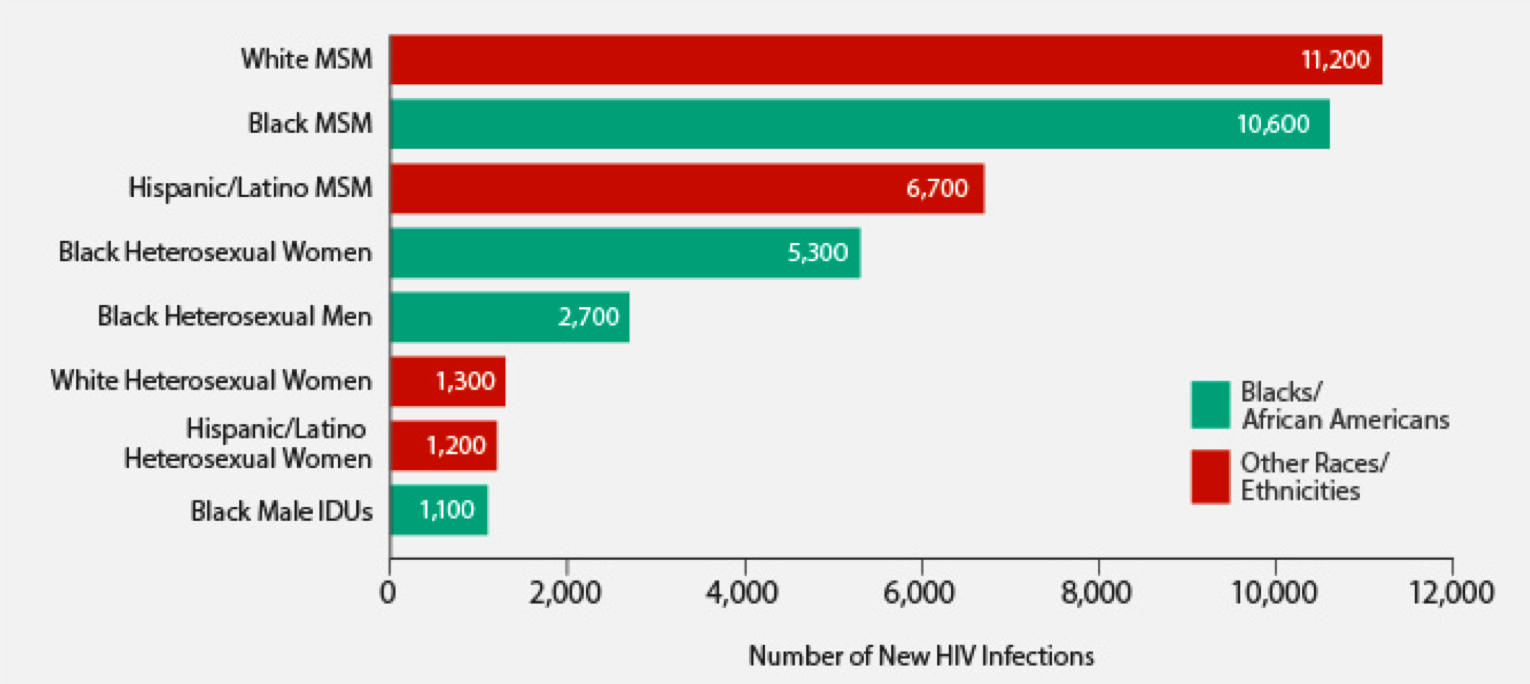

Of all racial groups, African Americans suffer the most from HIV. Of all racial groups, black women have the highest breast cancer death rates; they're 40 percent more likely to die of the disease than white women.

The number of new HIV infections in the US by demographic group. Note, MSM means "men who have sex with men" and IDUs means "injection drug users." (Chart courtesy of the CDC.)

This disparity isn't only explained by differences in access to care. Even when black and white people have the same cancer screening, black people are more likely to die from the disease. The latest study on this issue examined the differences in cervical cancer treatment of black and white women in Maryland. Maryland was a good place to test that hypothesis, since there is a state-sponsored screening program to support women and black and white women are being screened at the same rate.

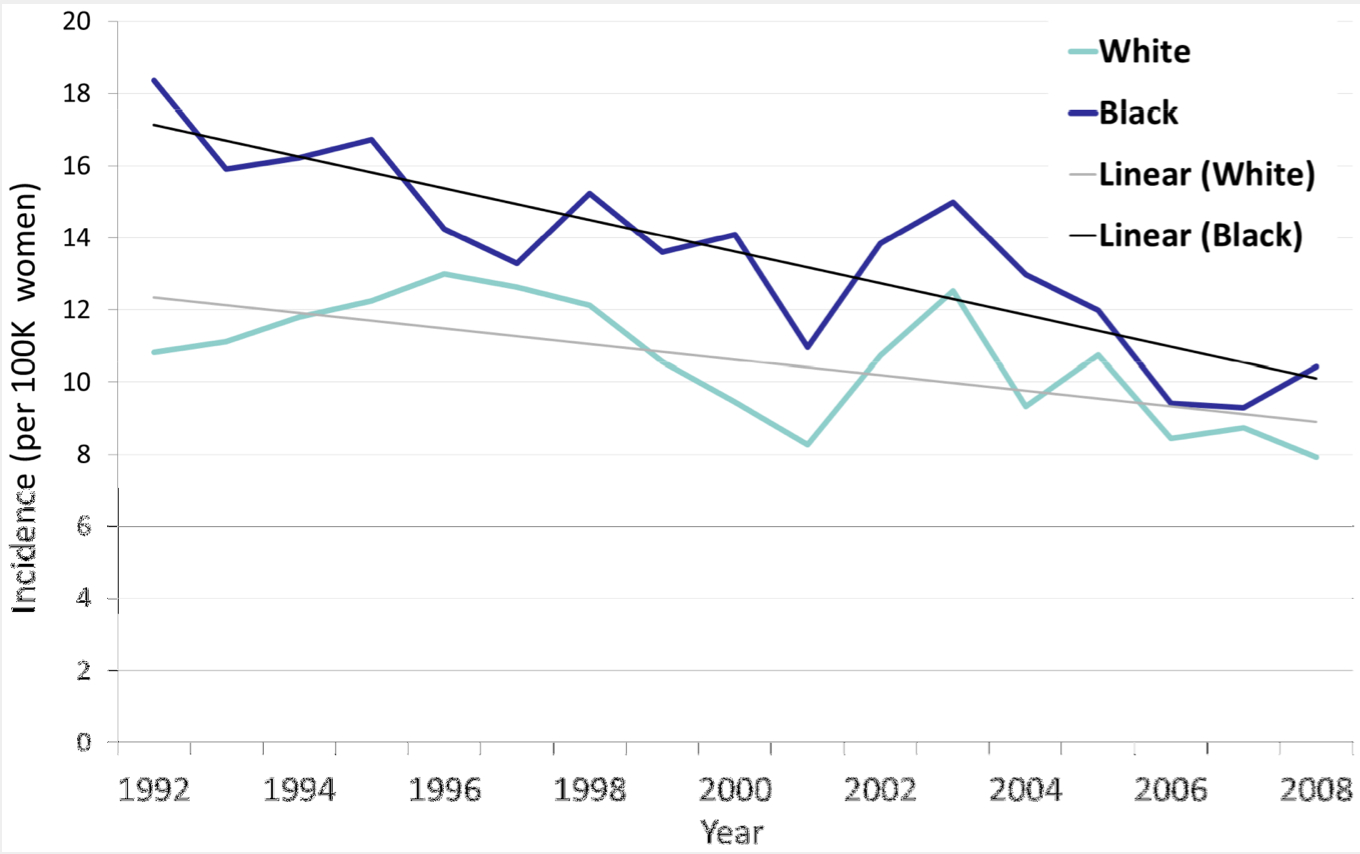

After accounting for stage of cancer at diagnosis, the treatments received were still different. White women got surgery more, while black women were more likely to get radiation or chemotherapy combined with radiation. Such a treatment disparity may be what's driving the fact that in the US, black women are more likely to have cervical cancer (see chart below) and twice as likely to die from it as white women.

(Courtesy of PLOS One)

Near the end of life, the disparities persist. Black people have the highest death rates from stroke and hypertension, and the largest incidence and highest death rates from colorectal cancer. Compared with white patients, black patients are much less likely to get the life-saving organ transplants they need.

One study looked at people with end-stage kidney disease in six states, examining their likelihood of being placed on a waiting list for a donor organ and whether they wanted a referral in the first place. The results are deeply disturbing. "In contrast to the relatively small differences in preferences and expectations about transplantation," the study authors wrote, "black patients were much less likely than white patients to have been referred to a transplantation center for evaluation; they were also much less likely to have been placed on a waiting list or to have received a transplant within 18 months after the initiation of dialysis."

Black women are treated the worst

One theme in this damning body of evidence is that black women are affected most by this disparity: they're the population that suffers from both a racial and gender effect. Take this classic study published 15 years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers presented 720 physicians from across America with one of eight random videos of an actor conveying symptoms and asked them to make health-care recommendations. The eight videos were exactly the same — identical script, identical emotions — except that the actors differed in age, sex, and race.

(Courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine)

Unfortunately, the physicians did not do so well. When the actors were women or black, the doctors were less likely to refer them for cardiac catheterization. Black women fared worst of all as the least likely group to benefit from doctors' recommendations to seek follow-up care. The study demonstrated that doctors sometimes carry deeply ingrained racial biases into the clinic, which can have a harmful effect on patients.

Black people have fewer years on Earth than white people

All these health disadvantages add up to a lifespan that's cut short: black men can still expect to live five years less than white men, and black women can expect to live four years less than white women. There are no biological or genetic explanations for this difference. Four and five years is a lot of life: it's the length of time it takes to complete college or to see your child through to kindergarten.

(Courtesy of the CDC)

Why the persistent gap?

Thomas LaVeist, director of the Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, has been studying racial disparities for decades. When he did his PhD dissertation in the 1990s, he calculated how many infant deaths were associated with being black, and the stunningly high numbers drained him. Since then, he says, not much has changed.

Even when you control for education and income, black people still fare worse than white people, and he thinks one key cause is everyday racism.

"These little microaggressions include things like going to a reception and sipping a glass of wine, and no one talks to you; trying to go into an elevator and someone doesn't hold the door for you; or walking into the elevator and someone moves further away as if they're concerned about you snatching their purse," he said. "These things are happening at a subconscious level, and they have a physiological and psychological response. That degrades your health, and it has been shown to degrade the strength of the immune system."

For years now, researchers like LaVeist have been meticulously documenting the ways black patients get inferior care and have worse health outcomes than other racial groups. Over a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine even published a definitive report on the subject, concluding that many of the differences in health care received between white and black Americans was the result of unacceptable discrimination.

The evidence is clear

We don't need more evidence about the existence of these unacceptable racial disparities and discrimination. When you look at the fullness of a life, and all the points at which that life intersects with the health system, and then at how much worse off black people fare every time, you can see there is a violence and injustice here.

That's something we should all fight against. LaVeist says some are already taking the first steps to address the problem. He's putting together a documentary about the black-white health gap, which highlights solutions. On the community level, he found educators in Los Angeles who are trying to teach people how to grow their own healthy food. In Mississippi, he found a pastor who banned soul food in his church. One woman in Nashville goes door to door teaching people how to do CPR, because so many studies have shown that African Americans are less likely to know CPR.

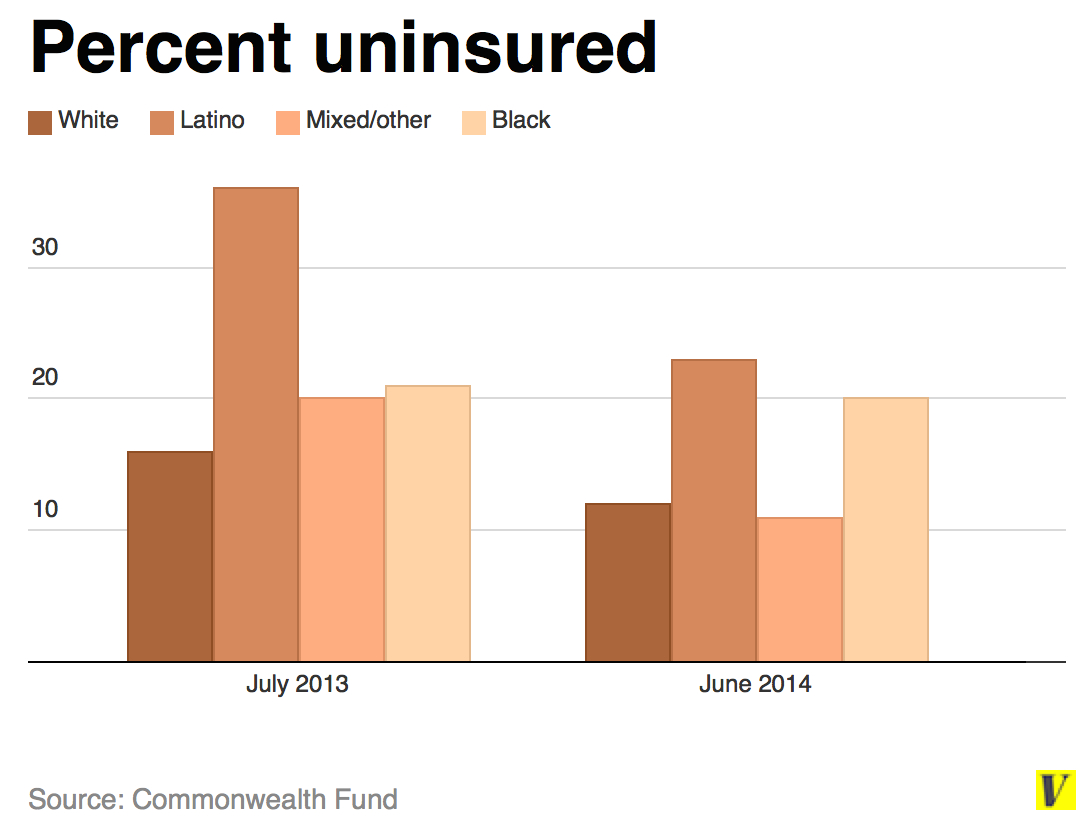

On the policy level, the Affordable Care Act has expanded access to more than 30 million people. "It's not sufficient to address the health disparities problem," says LaVeist, "but it's an important and necessary condition."

Still, evidence suggests that the ACA isn't working as well for black Americans as it is for other racial groups: their uninsured rates have only dropped from 21 percent to 20 percent since the legislation was introduced. So the ACA is a start — it's foundational — but it's still failing African Americans.

Right now, in 2015, despite all the advances of medicine in the past 100 years, despite this groundbreaking health-care legislation, despite having a black president in the White House, the black-white health gap isn't going away.

We often focus on medicine and the latest technology in health. Yet what dictates how healthy you'll be throughout life — and all the promise and opportunity that cascades from that — is something a lot more basic. In America, it's still the color of your skin.

Welcome to Burden of Proof, a regular column in which Julia Belluz (a journalist) and Steven Hoffman (an academic) join forces to tackle the most pressing health issues of our time — especially bugs, drugs, and pseudoscience thugs — and uncover the best science behind them. Have suggestions or comments? Email Belluz and Hoffman or Tweet us @juliaoftoronto and @shoffmania. You can see previous columns here.