The colour blue is a relatively modern invention. Prehistoric artists were strangers to it. You won’t find cerulean or azure in cave paintings. The ancient Greeks had no word for blue as we know it today – Homer described the sea as “wine-dark” in the Odyssey – and neither can it be found in the Icelandic sagas, the Koran, ancient Chinese stories or myriad other texts.

The only ancient culture to have a word for blue was the Egyptians, and they were also the only culture that had a way to produce a blue dye. Blue rarely appears in nature – there are few blue animals, fruits or vegetables – and the early painter’s palette was restricted to “earth colours”: reds, browns, yellows, blacks. Blue only appeared when the Egyptians started mining and unearthed lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone first found in Afghanistan about 6,000 years ago. Lapis was scarce and thus greatly prized, and was used to adorn the tombs of pharaohs and the eyes of Cleopatra.

Obtaining the colour from lapis was prohibitively expensive so, about 2,500BC, the Egyptians donned their lab coats, lit their Bunsen burners and headed for the ancient equivalent of the school science lab to invent the world’s first artificial pigment. By heating lime, sand and copper into calcium copper silicate, they discovered the royal-turquoise pigment Egyptian blue, which spread around the Mediterranean world and was widely used until about AD800.

Other ancient civilisations followed suit. In China, copper was blended with heavy elements such as mercury to create shades of blue. So new and exciting were the colours created that they were attributed healing qualities and mixed into poisonous “medicinal” concoctions. According to Heinz Berke, a chemist who has studied the history of blue pigment at the University of Zurich, “It is said that 40% of the Chinese emperors suffered from heavy-element poisoning.”

The Mesoamericans, too, created a vivid and durable azure blue. They used it in paintings, pottery and even, some scientists have suggested, to adorn the bodies of those destined for human sacrifice. Scientists know that Mayan blue’s two main ingredients are indigo and palygorskite, a type of clay, but the third ingredient – and the method used to create the long-lasting paint – are still hotly debated.

Wherever it came from, blue pigment remained costly to produce. It was an expensive, aspirational colour – and it peaked in the year AD431, when Virgin Mary worship and the use of her image was sanctioned by the Christian church at the Council of Ephesus. Images of Mary became wildly popular, and she was usually depicted wearing a blue robe, as befitting the queen of heaven. The colour came to symbolise truth, peace, virtue and authority.

Blue remained the colour of the rich and the divine until the industrial age – with one notable exception. Workaday woad, a plant used as early as the stone age, was used to create a blue fabric dye. The leaves were dried, crushed and composted with manure – which, as you might expect, was a rather stinky process. It was also not colourfast, and had a far less intense colour . It was, then, strictly the poor relation of the royal blues and azures, used only for clothing worn by the (smelly) masses.

But with the advent of modern manufacturing methods, cheaper blue pigments became available, not least in paint. The colour was used to capture different moods by artists: Pablo Picasso, for instance, had his Blue period after moving from Paris to Barcelona in 1901. During the next four years, the paintings he produced in shades of blue and blue-green seemed to reflect his experience of relative poverty and instability, with gloomy subjects: beggars, street urchins, the old and the frail and the blind.

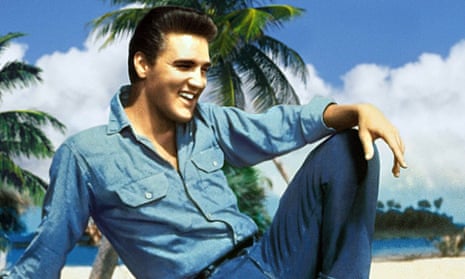

Racing through to the 1950s, the now readily available blue permeated all areas of life, including fashion and music, from Elvis’s Blue Suede Shoes to the rise and rise of blue denim jeans. Invented by Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis, and popularised by James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, blue jeans became a wardrobe staple. The indigo dye gave denim a unique character: it doesn’t penetrate cotton like other dyes, but sits on the outside of each thread. The dye molecules erode over time, causing the fabric to fade in a unique and personal way.

Today, we see blue everywhere we look, and in every shade we can think of. It is in uniforms, from the navy to nurses, and in our houses, where it may be associated with clear skies, healing and refreshing waters. Blue may not have been around for as long as earthy red, yellow and black, but its popularity shows no signs of waning.