“Who is Jeremy Corbyn?” asked NBC News, scrambling to catch up a few days before the general election last week and asking a question that echoed across US media. Before the results came in, the answer, on NBC at least, was a man whose distinguishing characteristics were that he had been in politics for four decades, “often gets around the capital on a bicycle”, and, most startling of all to the American political class, “lives in a small house”. “Despite being a bit shambolic,” said NBC – before explaining that shambolic was “a British word meaning dishevelled and disorganised” – Corbyn “has shown he has a common touch”.

High up in the hastily assembled profile in New York magazine meanwhile, came mention of Corbyn’s “hobby of drain-spotting”. This, it was explained, involved the Labour leader photographing “manhole covers for fun”.

Since the results came in last Friday, however, the tone of much of the Corbyn coverage in the US has changed. The quirky, bearded leftie taking pictures of manholes has been replaced by someone who came within sniffing distance of No 10 and may get there yet, setting off alarm bells across the American media. “The wrong man for the moment,” suggested a piece in Slate, which scathingly described Corbyn as “a leftist whose open admiration for Hamas and Hugo Chávez makes him a more natural ally to Jill Stein than to Bernie Sanders”. Politico ran a highly critical piece by James Rubin, former assistant secretary of state under Bill Clinton, calling Corbyn a “useful idiot” for the Russians, who has made a career “of attacking US foreign policies time and again”.

In the Atlantic, Corbyn was described as “the underdog populist from beyond the Westminster bubble”, before being compared to Trump. That is, as a man of “creepy extremism”, and “garish flaws”, whose rise should worry the west. What a difference a week makes.

Liberal with the insults

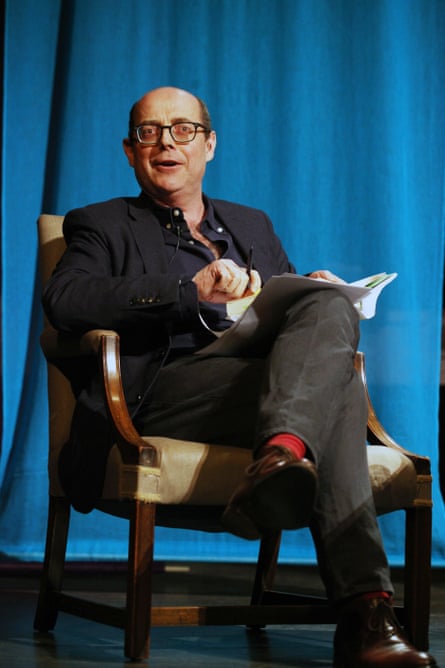

The most depressing thing on election night was watching the commentary on women politicians drift from the political to the personal, primarily to matters of appearance. At some point in the night, my timeline filled up with self-styled liberal men calling Theresa May a “whore”, reviving the line about Nicola Sturgeon looking like Jimmy Krankie, and suggesting that the two of them, plus Ruth Davidson, form a “girl band” or bugger off on a “girls’” holiday to Ibiza. Even Nick Robinson, on the BBC, started banging on about how much makeup May was wearing, which was a bit rich. In keeping with political correspondents going back to John Sergeant, Robinson should look in the mirror, look at his career in TV, and thank his lucky stars he’s not female.

Curious Georgina

A friend recently gave me a set of five Curious George books, the children’s series written by HA Rey and his wife, Margret, between the 40s and 60s, and later turned into a long-running cartoon. Curious George, as millions of American children know, is a monkey who gets into all sorts of trouble, but for which things generally turn out well in the end. At least, this is the case in George’s TV incarnation.

Things are a little different in the original books. For a start, in the first book, written in 1941, George is kidnapped by an American anthropologist from an unidentified jungle in Africa and shipped across the Atlantic to be put in a zoo, an origin story the TV version decided to leave out. (In the show, George lives in an apartment in Manhattan.) On TV, when George misbehaves, nothing much happens. In the books, he is carted off to prison or punished with illness, breaking an ankle after falling from a fire escape while being chased by a woman whose apartment he ruined. “He got what he deserved,” says the woman.

My children love the books more than they care for the TV show, thrilled by the drama and dire retribution, and I’m fine with that, except in one detail. In the books, when George goes to the hospital, all the doctors are men and all the nurses are women. My girls are too young to recognise these jobs in pictorial form, so it’s nothing a little live editing can’t fix.