The disaster in Nepal is heartbreakingly close to the worst-case scenario for any region in the world vulnerable to earthquakes—a “nightmare waiting to happen,” in the words of one seismologist. As of Sunday afternoon, more than 2,500 people had died across the country—placing the earthquake among the two-dozen or so deadliest quakes worldwide over the past 40 years. The tragedy is only compounded when we consider how badly prepared the nation was for such an event, a fact that is sadly still common among developing nations in earthquake zones. In a world that’s getting better at preventing disasters, Nepal and other poor countries continue to bear the brunt of tragedy.

As aid begins to arrive, so are estimates of the quake’s ultimate impact on Nepal. The U.S. Geological Survey’s PAGER model gives a 52 percent chance of more than 10,000 deaths and also projects that the total economic losses “may exceed the GDP of Nepal.” The country’s economy is strongly tourism-dependent, and the sheer destruction to the country’s infrastructure may depress the economy for years.

What’s more, it was not far from the strongest earthquake scientists believe is possible in the Himalaya region, and it hit at about the worst time in the calendar year—just before the start of monsoon season. According to the United Nations, local hospitals are overloaded and “post-earthquake diseases are a concern,” especially as thousands of survivors will now be exposed to the elements. Io9 reports that in many ways this earthquake is fated to be a lingering disaster, and landslides will likely be more common this year as the ground slowly settles.

The tragic situation in Nepal is one that developing nations are especially vulnerable to. As a whole, the world is getting much better at preventing large earthquakes from causing deaths in great numbers, but poorer countries like Nepal are getting left behind. The nonprofit GeoHazards International says that over the past few decades, rich countries have reduced mortality from earthquakes at a rate 10 times faster than poor countries.

Slate

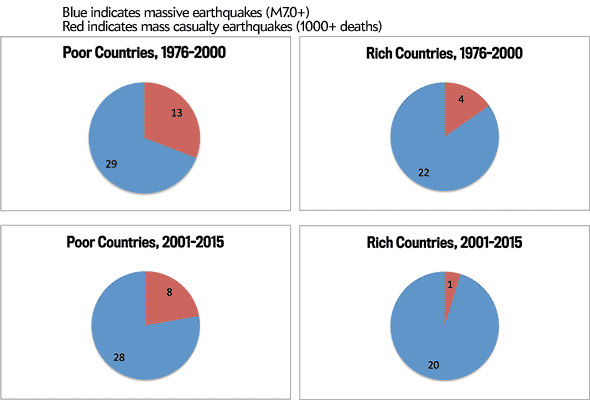

Looking at just the biggest earthquakes, rich and middle-income countries (those with a per capita GDP above $10,000 USD) have reduced their risk of mass casualties by nearly fourfold since 2001, when compared with the period from 1976 to 2000. While the poorest countries have also improved, they’ve cut down their risk by less than 40 percent, a much slower rate.

According to my analysis of U.S. Geological Survey data, since 1976 there have been 99 earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or greater that caused significant shaking on land (the others either happened at sea or were too deep underground). Twenty-six of them caused more than 1,000 deaths, including Saturday’s quake in Nepal. But only five of these disasters occurred in rich or middle-income countries—including the 2011 9.0-magnitude earthquake and tsunami centered in Sendai, Japan. In fact, just Japan, the U.S., and Chile—all relatively wealthy nations—have combined for nearly a quarter of those 99 earthquakes, with Sendai’s being the only major tragedy.

The track record in poor countries is a different story. Over one-third of the earthquakes to cause severe shaking over the last four decades (21 of 57) have resulted in mass casualties. The disparity between rich and poor has been worse since 2001: While just 19 percent of violent earthquakes worldwide have resulted in more than 1,000 deaths, nearly 90 percent of them have been in poor countries.

So what makes places like Nepal and Haiti so vulnerable to earthquakes? Poverty is a big factor, but so is politics. Preparedness funding routinely returns five dollars for every dollar spent. But governments with low resources find it difficult to justify extra spending to mitigate even likely disasters. Nepal, one of the world’s poorest countries, ranks near the bottom in a list of countries working to reduce their risk. Even in the United States, spending on disaster relief routinely outstrips investment in disaster preparedness by at least a factor of 10.

Just last month, representatives from world governments agreed to a 15-year plan to reduce global disaster risk, especially in the poorest countries. The previous agreement—the first-ever global agreement on disaster reduction—was reached in 2005, in the aftermath of the South Asian tsunami. However, disaster experts warned that the new goals come without much additional funding from rich countries (only Japan committed significant money). And without more money devoted to preparedness, the world will be severely limited in its ability to prevent tragedies like Nepal’s.

Read more about the Nepal earthquake in Slate: