Before starting my GP clinic yesterday I glanced through the list of patients I’d see that day. Most of the names I knew relatively well: their appointments would be follow-ups on diabetes, mental health problems, heart disease, or any number of the myriad difficulties many of us struggle along with. Other names I knew less well: one turned out just to need her contraceptive pill, another had broken his wrist, yet another felt overwhelmed by a paralysing sense of despair. One of the rewards of this often difficult but fulfilling work is that when my patients take their seat in the consulting room, I never know what they are going to say. I have between 10 and 12 minutes allocated per patient, but, as for most GPs, this is never enough.

The first patient was a new name new to me. With a click of the computer his records popped up on screen, and I noticed his date of birth was last week. He was just a few days old; our consultation together would become the first entry into notes that, all being well, will follow him for the next eight or nine decades. The emptiness of the screen seemed to shimmer with all the possibilities that still lie ahead of him.

From the waiting room doorway I called his name. His mother was cradling him to her breast; she heard me and got gingerly to her feet. She smiled and made eye contact then, with the baby still in her arms, followed me back to the office.

“I’m Gavin Francis,” I said, as I showed her where she could sit, “one of the doctors. How can I help?”

She glanced down at her son, with a look of both pride and anxiety, and I watched her deciding how to begin.

❦

As a child, I didn’t want to be a doctor; I wanted to be a geographer. I didn’t want to spend my working life in a lab or a library; I wanted to use maps to explore life and life’s possibilities. I imagined that, by understanding how the planet was put together, I’d reach a greater appreciation of humanity’s place in it, as well as a skill that might earn me a living.

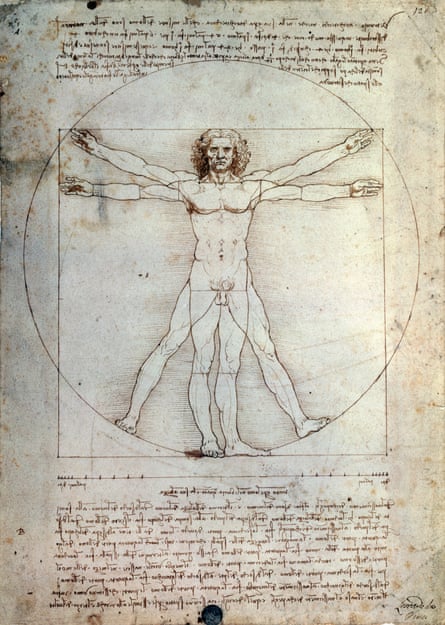

As I grew older, that impulse shifted from mapping the world around me to the one we carry within; I traded my geographical atlas for an atlas of anatomy. The two didn’t seem so different at first: branching diagrams of blue veins, red arteries and yellow nerves reminded me of the coloured motorways, A-roads and B-roads of my first atlas. There were other similarities: both books reduced the fabulous complexity of the natural world to something comprehensible, something that could be mastered.

The earliest anatomists saw a natural correlation between the human body and the planet that sustains us; the body was even a microcosm – a miniature reflection of the cosmos. The structure of the body mirrored that of the Earth; the four humours of the body mirrored the four elements of matter. There is sense to this: we are supported by a skeleton of calcium salts, chemically similar to chalk and limestone. Rivers of blood wash into the broad deltas of our hearts. The contours of the skin resemble the rolling surface of the land.

A love of geography never left me; as soon as the demands of medical training lessened I began to explore. Sometimes I found medical work as I travelled, but more often I journeyed just to see each new place for myself – to experience variety in landscapes and peoples and become acquainted with as much of the planet as I could. I have written books that try to convey something of the insights those landscapes have given me, but my work has always brought me back to the body, as my means of making a living, and as the place from which all of us start and end.

After medical school I began training in emergency medicine, but the fleeting contact with patients began to erode my sense of satisfaction from the work. I’ve taken jobs as a paediatrician, obstetrician and a physician on a geriatric ward. I’ve been a trainee surgeon in orthopaedics and neurosurgery. In the Arctic and the Antarctic I’ve been an expedition doctor, and in Africa and India I’ve worked in simple community clinics. These roles have all informed the way I understand the body: emergency situations are extreme and offer a heightened awareness of human lives at their most vulnerable, but over the years some of the deepest and most rewarding insights medicine has given me have been from quieter, everyday encounters.

Through my encounters in the clinic, I’m often aware of the ways humanity’s finest stories and greatest art can resonate with, and help inform, modern medical practice. Doctors do their jobs better when they are up to date with the science behind the treatments they prescribe, but also when they acknowledge the importance of culture, metaphor and meaning in the way we make sense of our lives. Sometimes I feel the need to take a step back from the white-tiled walls and jargon of the clinic and see medical practice in a broader context: embedded at the heart of human lives, with all their complications, disappointments and celebrations. The body is a kind of landscape after all – the most intimate one – and a storehouse of almost indescribable marvels.

There was a time when if you wanted a good day out you might go along to see a public dissection – the bodies of criminals would be laid out in a public space and anatomised. The popularity of these events was not just educational, of course – it was partly about voyeurism, but it also spoke to a deep need to glimpse deeper into the mystery of our own humanity. It was considered entertainment to see life and death stripped back to essentials; the physician-anatomist was like a guide exploring inner space. These events became popular in the 16th century but had their roots in public spectacles of the Romans.

Public dissections fell out of fashion around the time doctors were growing in power: no longer guides to a mysterious inner kingdom, but autocrats protecting secret knowledge. That paternalistic attitude reached a high point perhaps two or three decades ago, but is increasingly out of fashion. The time might be right to bring back public dissection, but instead of using scalpels and saws, I prefer to cut up the body using stories, literature and art.

❦

Take the eye: my medical office has a large, east-facing window, and for most of the year I examine my patients in natural light. The exception is when they complain of a deterioration in their sight, when I want to look inside their eyes with an ophthalmoscope. Then it’s necessary to close the blinds and feel my way in the darkness, hands outstretched, back towards the chair where the patient sits. The ophthalmoscope fires a beam of light through a small aperture, I place it close against my own eye then move within millimetres of the patient’s. There are few examinations more intimate: my cheek often brushes theirs, and usually both of us, through politeness, end up holding our breath.

It is an unsettling experience to project an image of someone’s inner eye so neatly into your own, retina examining retina through the intermediary of the lens. It can be disorientating too: gazing down the axis of the beam is like looking up into the night sky with an eyeglass. If the central retinal vein is blocked, the resultant scarlet haemorrhages are described in the textbooks as having a “stormy sunset appearance”. I sometimes see pale retinal spots caused by diabetes, and they are reminiscent of cumulus clouds. In patients with high blood pressure the branching, silvered shine on the retinal arteries resembles jagged forks of lightning. The first time I looked into the curved vault of a patient’s eyeball I was reminded of those medieval diagrams that show the heavens as an upturned bowl.

❦

In my second year at medical school I was given a brain to dissect. I remember the moment I held a human brain in my hands for the first time. It was heavier than I had anticipated; grey, firm and laboratory-cold. Its surface was slippery and smooth, like an algae-covered stone pulled from a riverbed. As I cradled the brain in my hands, I tried to think of the consciousness it had once supported, the emotions that had once crackled through its neurons and synapses. I wondered, then, if peering into the brain might bring me closer to understanding the idea of the soul. One of my classmates had studied philosophy before medicine; she took the brain from my hands and asked me if I knew how to find the pineal gland.

“What’s the pineal gland?” I asked

“Haven’t you heard of Descartes? He said it’s the seat of the soul.”

Some years later I became a trainee neurosurgeon and began to work with living brains every day, long days and nights in which I soon came to treat them as bruised or bloodied organs like any other. There were the comatose and catatonic, the car-crashed and gunshot, the aneurysmal and haemorrhagic. There was little opportunity to think about theories of the mind, or the soul.

❦

A night shift in a provincial emergency department, and there was a six-hour wait to be seen: I went to the waiting room and asked if anyone felt they could go home and return the following day. After a few moments a man at the back wearing a boiler suit and work boots got up. He was young – in his early 30s – with long sideburns and a splendid keel of a nose. His hand was wrapped in an old beach towel. “I can probably come back tomorrow,” he said.

I took him into an adjacent cubicle. He told me his name was Francis, and as I unwrapped the towel I jumped back: there was a nail through his palm.

“There’s a nail through your palm,” I said, pointlessly.

“I know.”

“What happened?”

“I was working late on the house, was getting tired … and fired the nail gun by mistake.” The nail was clean, about four inches long; the puncture wounds on each side were neat with a halo of dried blood. “I’m lucky it didn’t fire right into wood,” he laughed, “or I might still be there, pinned to a beam like Jesus.”

Within the palm of the hand are four bones – the metacarpals – one for each finger. A fifth supports the base of the thumb. Between each bone are the delicate nerves that supply sensitivity to the fingers, some blood vessels, and also the muscles that splay the fingers or bring them tightly together. The metacarpal bases are bound to the bones of wrist by tough ligaments, but further out, towards the fingers themselves, they are held fairly loosely. It’s quite possible to fire a nail through the palm of your hand without causing any major damage: the nerves are narrow and run close to the bone, and the main blood vessels run in a broad arch from the heel of the hand around the bases of the fingers. Firing a nail through the wrist would be a different matter: it has a tight, seed-like intricacy of nerves, blood vessels and interlocking bones.

Francis joked about crucifixion, but if you wanted to nail someone to a piece of wood, you wouldn’t do it through the palm of the hand. The same anatomical features that allow a nail to pass through without causing serious damage mean that its structures aren’t strong enough to support the body’s weight. The tissues would rip and your hand would come free – mutilated and useless, but free.

Francis’s fingers were all flexing normally and his sensation was undamaged: none of his nerves or tendons were hit by the nail. The x-ray of his hand showed the nail passing beautifully between the metacarpal bones, as if shot through the bars of a cage.

After cleaning up his wounds, the plastic surgeons pulled out the nail in an operating theatre. No matter how neatly the wound healed he would be left with stigmata on either side of his hand; a lifelong reminder of the night he was almost nailed to a beam.

❦

In that emergency department there was a concealed door that led to a small yard out back. Ambulances would bring patients there when they were already dead. Rather than their arriving with flashing blue lights at the main entrance there would be a discreet knock on the door, and one of us doctors would go out and certify the body so that it could be taken to the mortuary. There are three tasks to remember when certifying the dead: shining a torch in the eyes to see if the pupils narrow in response to the light, checking the carotid artery at the neck to feel if there is a pulse, and putting a stethoscope on the chest to hear if there is any breath. The breath is the most telling; in Renaissance times a feather would be placed on the lips to see if air was moving in and out of the lungs. The textbooks recommend a full minute of listening, but I’ve often done it for longer – afraid that I’d miss an agonal gasp, or one final, feeble beat of the heart.

Traditional Chinese, Ayurvedic and Greek medicine all maintained that the air in breath carries invisible spirits or energies. From those perspectives our bodies are bathed in spirit, our lungs the interface between the spiritual and the physical world. For the Greeks, as commemorated by St John’s gospel, the first principle was logos – the word – the world conjured into being through sounds produced by the breath. Written texts, even those never intended to be read aloud, are often punctuated according to the needs of a speaker to take breath.

The lungs are light as spirit because their tissue is so thin and delicate; the membranes within them arranged so as to maximise exposure to breath much as the leaves on deciduous trees maximise exposure to air. If you were to stretch flat all the membranes of an adult’s lungs they would occupy more than a thousand square feet; equivalent to the leaf coverage of a 15- to 20-year oak. Listening with a stethoscope you can hear the flow of air across those membranes, like the rustle of leaves in a light breeze. When doctors listen to the breath, that’s what they want to hear: an openness connecting breath within lungs to the sky; lightness and the free motion of air. When I think about lungs the associations that come to mind are of light, airiness and vitality.

❦

One night a man was brought in dead after he had jumped from a bridge on to the road below. Bystanders said he’d had no hesitation, just leapt over the parapet to his death as if he’d dropped something precious and wanted to get it back.

His was a messy corpse. His neck was badly broken and distorted, his tongue and neck were swollen, but there was little bleeding from his grazes – his heart must have stopped pumping almost immediately on impact. I shone a torch into his eyes and watched the light drop into their vacant stare – there was no narrowing of the pupils, or reflection of the light from their surface. Moving on to his carotid pulse I felt something unexpected: beneath my fingertips there was a popping and crackling sensation. After checking he had no pulse, I placed my stethoscope against his chest wall and heard the same crackle amplified through the ear pieces. His lungs must have burst, I realised, exploded with the pressure as he hit the road. The popping and crackling was caused by air, ordinarily contained within the lungs, but now tracking out into the other tissues of the body.

Liquid and air must keep to their separate compartments in the body, just as a horizon separates the sea from the sky. Even if his eyes and lack of pulse or breath sounds hadn’t convinced me he was dead, this would have. As I listened for a breath sound that didn’t come I imagined how it must feel to launch oneself from a bridge; how light and free it might feel if only gravity, and the blackness of despair, weren’t pulling you down to the earth.

❦

Thanks to the secular miracle of organ transplantation a kidney is now perhaps the most valuable gift that someone can freely give – when I talk to transplant donors and recipients, I’m astonished and humbled by the generosity involved in offering a kidney that will benefit a stranger. Organ donation by someone who has suffered brain death can present the gift of life to not just one individual, but several. In surgical theatre I’ve seen the results of that gift: a donated kidney that was cold, shrunken and dusky grey – barely recognisable as an organ – when plumbed in to a recipient’s body underwent the most astonishing transfiguration. It was like watching a process of reanimation – a repudiation of death. Each beat of the patient’s heart, visible in the pumping of the arteries, caused the kidney to swell, and its defeated, dimpled surface began to fill out to a lucent pink.

❦

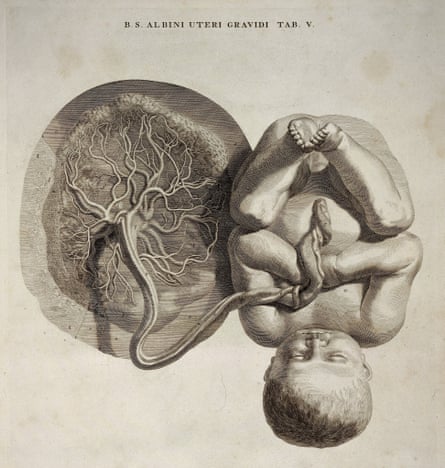

At first glance, umbilical cords seem to come from the sea: opalescent and rubbery like jellyfish fronds, or stems of kelp. They are torqued in a triple helix of blood vessels: twinned arteries spiral around a single vein, braiding through greyish jelly composed of a substance used in only one other place in the body – the refractive humours of the eye. The wrinkle-faced, bunch-fisted girl I had just delivered was already squalling, and I dried her with a towel and held her down beneath the level of her mother’s hips for a moment. The placenta was still inside her mother’s pelvis – in these first moments I wanted to let blood run from it down into the baby’s body. I put my fingers again on the cord, feeling the pulse of her tiny heart fluttering within it like a trapped moth. “Is everything all right?” asked her father. He looked stunned by sleeplessness, and the agonies of labour he had just witnessed in his wife.

“Fine,” I said, “absolutely fine.” As I watched the girl, my fingers on her cord, the pulse in it thinned out and then stopped – a reaction to the coolness of the air and the higher oxygen levels in her blood now that she was breathing for herself.

For the delivery the mother had been on all fours, but as I cut the cord, and handed her daughter up to her, she heaved herself on to her back. As mother, father and baby dissolved into a universe of three the midwife and I looked down at the business end. This wasn’t over yet.

With a pair of steel tongs I gave the gentlest traction to the end of the cord. The baby was already at her mother’s breast: as she sucked, hormones hastening the let-down of milk also caused the womb to tighten. As I pulled, the cord suddenly widened the way a tree trunk does just before its roots spiral into the earth. The “afterbirth”, a violet clot of blood, slithered out on to the bed.

It was heavy – more than half a kilogramme – almost round and about an inch thick. Since early in the pregnancy, it had carried oxygen, sugar and nutrients towards the developing baby, as well as transporting carbon dioxide, urea and other by-products back to the mother. The blood of mother and baby don’t mix, but the capillaries belonging to each are approximated so closely that it’s as if a million tiny hands locked fingers across the placental divide. Da Vinci noticed this distinction over 500 years ago, when many of his contemporaries still believed that babies grew by consuming their mother’s menstrual blood. Leonardo’s placental drawings betray a familiarity with the afterbirth of the sheep: European men through the centuries seem to have had more familiarity with sheep placentas than those of their own children. Even the scientists’ word for the placental membrane, amnion, is taken from the Latin for “lamb”.

Until recently, placentas and umbilical cords were thrown out with the rubbish, and burned in the hospital incinerator. In wealthy, modern, healthcare systems, a new possibility has arisen: to have it cryogenically preserved. Buried in the jelly of the umbilical cord are cells that are genetically identical to the baby, but which have not differentiated into any particular tissue type. These undifferentiated cells are a type of stem cell, because just as it’s possible to regrow a tree from a single cutting, they are stems from which other body parts can theoretically grow. The cells within the cord blood have the potential to develop into tissues such as bone marrow, while the cells within the jelly of the cord are related to the structural components of the body: bone, muscle, cartilage and fat.

Some cultures have always maintained that a baby’s visceral connection to its umbilical cord is an association that lasts a lifetime, and for that reason the cord must always be handled with respect: it is common to bury them beneath a sacred or special tree. Cryogenics companies agree, but maintain your baby’s lifetime association with the cord through regular bank payments. Within a decade we’ve gone from throwing afterbirth out with the rubbish, to reinvesting it with a depth of significance that had almost been forgotten.

❦

As a trainee neurosurgeon, I hoped to learn more about the elusive connection between brain and mind, but one of the most dramatic examples of a physical treatment to alter mental experience is not practised by neurosurgeons, but by psychiatrists. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) is used less now than in decades past, but it is still sometimes recommended for people with certain kinds of severe or psychotic depression.

On my first visit to see ECT performed I was hesitant outside the department, unsure if I should enter. The door was ajar; inside I could see whitewashed walls, and a bleaching light shone in through the windows. The floor was covered in the sort of linoleum you see in operating theatres, cambered to rubber skirting boards so that dirt and germs have few places to hide. In the centre of the room was an iron-framed bed stretched with a pressed white sheet.

There was an anaesthetist with his back to the door; as I entered the room he turned to greet me. A medical monitor on a rolling stand stood next to the bed. There was a tray of anaesthetic drugs, a defibrillator in case of cardiac arrest, and a tank of oxygen attached to a mask. All this equipment was familiar from the emergency department, but it was startling to see it here in an environment more used to psychology, occupational therapy and pills. The ECT generator itself was a compact blue box with plugs, switches and a series of wires. It had a dashboard of ruby LEDs, like the timer on a Hollywood bomb.

I had already met the patient – let’s call him Mr Edwards – who was wheeled in and helped on to the couch. He had become immobilised by severe depression, was losing weight quickly because he couldn’t eat, and, just before being admitted to hospital, had become convinced that his body was rotting from the inside. He said nothing, just looked blankly at the ceiling, while the anaesthetist slid a needle into his vein. Two drugs were injected into the needle: a short-acting anaesthetic and a muscle-relaxing agent (otherwise the spasm provoked by an ECT seizure can cause injury to bones and muscles). Once paralysed and anaesthetised he had a plastic tube inserted into his mouth to stop his tongue from slipping back.

The consultant placed two cylindrical metal electrodes, like judge’s gavels, against each of Mr Edwards’s temples. He quivered, his arms flexed, and his body began to twitch and shudder.

“These tonic-clonic movements are actually pretty minimal,” the anaesthetist said, reassuring me. “If we hadn’t paralysed him, they’d be far more intense.”

After only 20 or 30 seconds his arms dropped to the couch. We rolled him on to his right side, and, after checking that he was breathing well, pushed him on the trolley through to another room.

“There’s a lot of superstition around ECT,” the consultant said as she reached the door, “but in my opinion it’s one of the safest, and for some individuals the most effective, therapies we have.”

Mr Edwards was put on a regime of two treatments a week. At first there was little improvement, but after a while his facial expression, having previously been blank, would alter when I or one of the nurses went to speak with him. He seemed startled by life, like a Lazarus unconvinced that he had been done a favour.

Literature has darkened the reputation of ECT in the popular imagination: in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, it’s an instrument of torture, while for Sylvia Plath in her novel The Bell Jar it’s alternately terrifying and transcendental: terrifying when administered by an uncaring doctor; transcendental when delivered by someone more compassionate. For Plath, ECT seems both sacred and profane, like a punishment and a cure – the tone of The Bell Jar (and also her poem “The Hanging Man”) suggests it has the power of damnation and redemption. It’s notable that in many of the deeply negative accounts of ECT in literature, the recipient wasn’t sedated and anaesthetised for the treatment – modern patient experience is, for most people, far more benign.

For the ancient Greeks, seizures were the Sacred Disease – evidence of a direct communication between the physical body and a spiritual realm. It’s an understandable belief – the first time I saw someone collapse with a fit, convulse, then drift off to sleep, it was as if I had watched a process of possession, catharsis and sanctification. No one knows how changing the electrical state of the brain might help those in a state of extreme mental distress: is it the effect of the electricity itself that is of benefit, the changes in neurotransmitters caused by the seizures, or the circumstances around receiving the treatment? ECT disrupts some of the neuronal connections involved in memory, and some psychiatrists think it induces certain neurotransmitters in the brain which have a specific antidepressant effect. Other, Freudian-minded thinkers have gone as far to propose that the seemingly drastic nature of ECT may work by offering redemption from feelings of intense guilt – a position not too distant from that of the ancient Greeks. It’s a powerful therapy socially, psychologically and neurologically, which has the potential to disrupt the coherence of thought. But when your habitual state of mind is one of penetrating, paralysing anguish, having the coherence of your thought disrupted can by in some instances be experienced as a reprieve.

Details about Mr Edwards’ slide into despair began to emerge as he talked. “It came over me so slowly,” he said. “For a long time I think I didn’t notice anything was wrong. It was like a heaviness on me, a suffocating fog.” The treatment seemed to blow back that fog: within three weeks of starting it he was gaining weight, and was soon ready to go home.

For all its negative press some people do benefit from ECT, though the testimony of Plath’s The Bell Jar is that the way doctors speak with their patients – how compassionate, empathetic and supportive they are – can have as much influence on recovery as the treatment prescribed. From this perspective, increasingly recognised in research, it’s not the therapy that makes the biggest difference, but the therapist. As in many areas of psychiatry, Freud got there first: “All physicians, yourselves included, are continually practising psychotherapy, even when you have no intention of doing so and are not aware of it.” There is nothing sacred about seizures, but there just might be something sacred about a good doctor-patient relationship.

❦

My medical office is a converted tenement flat on a busy Edinburgh street. On summer mornings it’s luminous and warm, and in winter it’s sepia-toned and cool. A steel sink is set into one corner beneath cupboards stocked with sample bottles, needles and syringes, while in the other corner is a refrigerator for vaccines. There is an old examination couch behind a curtain, and on it, a pillow and a rolled-up sheet. One wall is lined with bookshelves, while others are decorated with Da Vinci’s anatomical drawings, noticeboards and certificates from specialist colleges. There is a chart of the city marked with the boundaries of the practice – a diagrammatic urban anatomy of coloured motorways, rivers and B-roads.

I journey through the body every day as I listen to my patients’ lungs, manipulate their joints, or gaze in through their pupils, aware not just of each individual and his or her anatomy but the bodies of all those I’ve examined in the past. All of us have landscapes that we consider special: places charged with meaning, for which we feel particular affection or reverence. The body has become that sort of landscape for me – every inch of it is familiar and carries powerful memories.

Imagining the body as a landscape, or as a mirror of the world that sustains us, can be difficult in the centre of a city. In terms of geography my practice area is relatively narrow – it’s still possible to visit all of my patients by bicycle – but the cross-section of humanity it encompasses is broad. It takes in streets of opulent wealth as well as housing estates of startling poverty; solid professional quarters as well as the student apartments of a university. To be welcomed equally at the crib of a newborn and in a nursing home, at a four-poster deathbed and in a burned-out squat, is a rare privilege. My profession feels like a passport or skeleton key to open doors ordinarily closed, to stand witness to private suffering, and, where possible, ease it. Often even that modest goal is unreachable – for the most part it’s not about saving lives, just trying to postpone death.

Medicine has been my livelihood, but working as a physician has also delivered me a lexicon of human experience – I’m reminded every day of the frailties and strengths in each of us. Beginning a clinic can be like setting out on a journey through the landscape of other people’s lives as well as their bodies. Often the terrain is well known to me, but there are always trails to be broken, and every day I glimpse a new panorama. The practice of medicine is not just a journey through the parts of the body and the stories of others, but an exploration of life’s possibilities: an adventure in human being.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion