Eduardo Galeano, Latin American author and U.S. critic, dies at 74

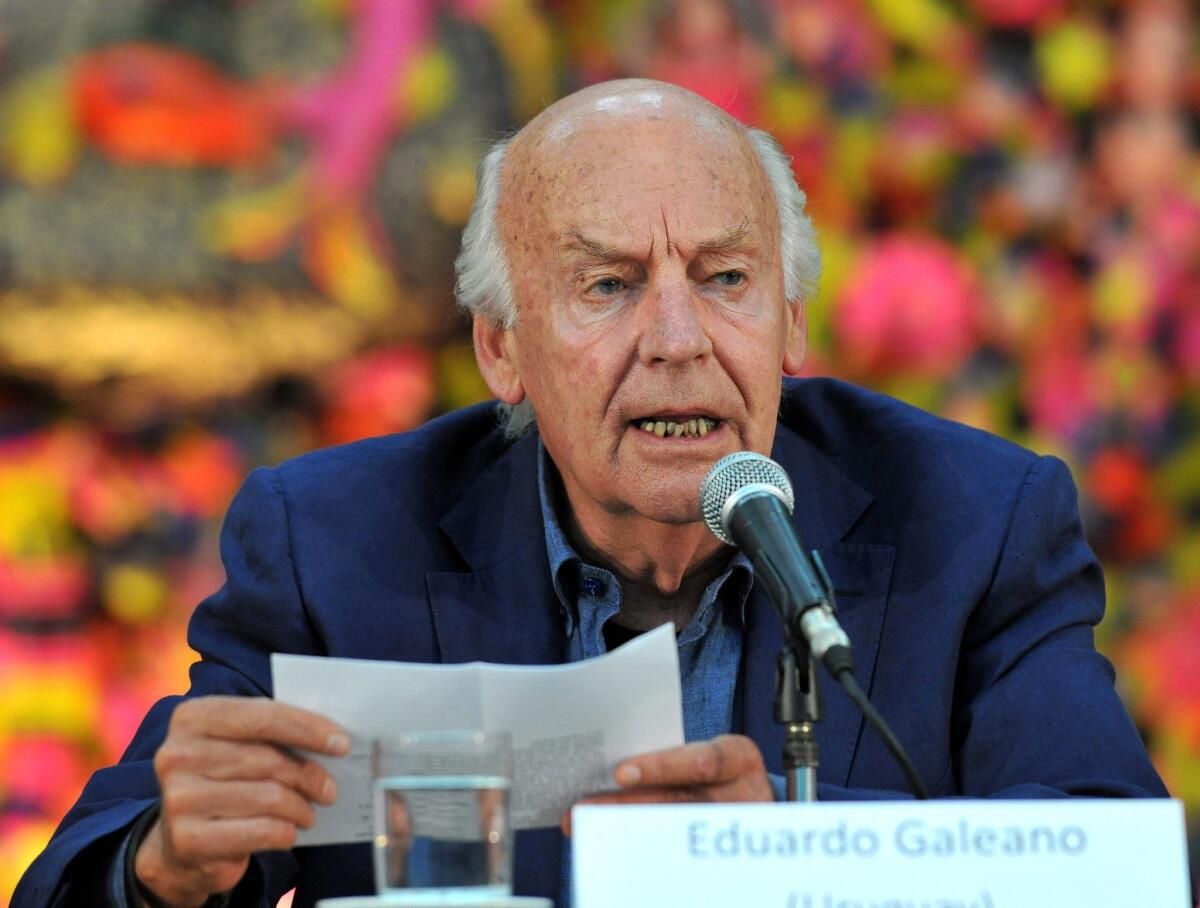

Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano in 2012.

Eduardo Galeano, a Uruguayan writer and committed socialist whose historical works condemning European and U.S. exploitation of Latin America over five centuries made him a revered figure among leftists, has died. He was 74.

Galeano died Monday in Montevideo after battling lung cancer, according to the weekly publication Brecha, where he was a contributor.

Weaving tapestries of sometimes obscure historical anecdotes, Galeano’s books presented alternative histories that gave equal weight to the sufferings of the downtrodden as to grand achievements of better-known historical figures. For some, the books were rallying calls. Galeano insisted he was merely trying to “unmask reality, to reveal the world as it is, as it was, as it may be if we change it.”

His best known book, “The Open Veins of Latin America,” published in 1971, described the historical legacy of the Spanish colonial era and capitalist plunder that followed it. He spurned conventional narrative in favor of anecdotes highlighting, among others, enslaved indigenous Bolivian miners, devastated Brazilian rain forests and polluted Venezuelan oil fields.

The book became a revisionist bible and soon a standard text in Latin American studies programs at U.S. and European universities. Galeano was not a professional historian and didn’t pretend to be. He described himself as a witness who sought to rescue Latin American history from academics who had “kidnapped” it.

Sales spiked on Amazon after Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez handed a copy of the book to President Obama at the 2009 Summit of the Americas meeting in Trinidad and Tobago to make a point that the hemisphere had long been victimized by First World greed and cultural imperialism.

Galeano didn’t spare Latin American governments, using vignettes showing a panoply of injustices including murders of reformers and modern-day subjugation of indigenous peoples. He knew firsthand the boot of oppression, having been arrested in 1973 by Uruguay’s right-wing military regime and forced into exile, first in Argentina, then in Spain until 1985.

Galeano followed “Open Veins” with the equally popular “Memory of Fire” trilogy, a series of vignettes of North and South America history that one Times reviewer described as a “poetic scrapbook.” Others used another metaphor to say the books were tapestries of outrage directed at perpetrators of murder and plunder.

“There is nothing neutral about this historical chronicle,” Galeano warned in the preface to “Memory of Fire.” “Unable to distance myself, I take sides.”

In a 1988 stop in Los Angeles on a national book tour, Galeano told a Times interviewer that his idiosyncratic style was an attempt to “recover memory as a key to open doors, not looking back but looking forward, not as an act of nostalgia but an act of hope.”

“That’s why I wrote [“Memory of Fire”] in the present tense — like Benjamin Franklin is waiting for a green light just at the corner now,” Galeano told the interviewer.

Latin America’s leftist leaders Monday paid homage. Bolivian President Evo Morales called Galeano a “maestro of the liberation of the people.” Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa said in his Twitter account: “Eduardo Galeano: Uruguayan writer and dear friend, the veins of Latin America are open because of your passing.”

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said in a statement that Galeano’s death was a loss for those fighting for a more just and united Latin America. “May his work and example of struggle remain with us to inspire us to build a better future.”

In an interview with the New Yorker magazine, Galeano said his method was to impress readers with the “beauty and reality of history.”

“Back in school, history classes were terrible — boring, lifeless, empty.... It was as if teachers were intentionally trying to rob us of that connection [to reality] so that we would become resigned to our present, not realizing that history is something people make with their lives, in their own present.”

Born of Spanish, Italian, German and Welsh ancestry, Eduardo Hughes Galeano was born Sept. 3, 1940, in Montevideo and was largely self-educated. In his teens he began drawing cartoons for the Uruguayan socialist newspaper El Sol and by 20 was editor of another socialist newspaper, Marcha.

But his leftist politics got him in trouble with the right-wing military dictatorship in Uruguay, one of many in Latin America that took power in the 1970s. After being forced into exile, Galeano saw his books banned by authoritarian regimes in Chile and Argentina, as well as in Uruguay.

But with the politics of many Latin American countries veering leftward in the 1990s in reaction to neoliberal economics, Galeano became a “monumental” figure, in Chavez’s words, and a beacon for political movements seeking to distance Latin American governments from U.S. and European influence.

In his 1978 autobiography, “Days and Nights of Love and War,” Galeano wrote about the murders, tortures and disappearances that have characterized brutal South American regimes in the last half of the 20th century. A reviewer in the Nation magazine said the book proved Galeano a “magical writer in the best sense of the word” whose “intensity and appeal” matched the continent’s best fiction.

Galeano also wrote “Soccer in Sun and Shadow,” a love letter to soccer that many aficionados consider among the best books ever written on the sport.

Galeano is survived by his third wife, Helena Villagra, and three children.

Special correspondent Andres D’Alessandro contributed to this story.

Kraul is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.