NEW BRITAIN, Connecticut -- Luisa Cintron, 25, is sitting up as straight as she can, perched on the edge of the neatly made bed that doubles as a couch inside her dimly lit apartment. She is wearing a sweater and slacks, talking about the government program that she says changed her life, and trying -- without much success -- not to get distracted by the 4-year-old talking loudly about Batman in the next room.

The 4-year-old is Luisa’s son, Maliek. And not so long ago, Luisa explains, Maliek wouldn’t have been talking about superheroes -- or anything else for that matter. At 18 months, well past the time that babies usually start forming words, Maliek was still “non-verbal” and communicating almost exclusively through gestures. “It was always pointing at this, crying at that,” Luisa says.

Delayed speech wasn’t Maliek’s only problem. He also had a severe case of eczema that caused him to bleed into his clothing and sleep fitfully, if at all. It further impaired his ability to learn, and made for yet more tension at home.

At the time, Luisa was working at a Mexican fast food restaurant. Childcare was a constant struggle, and so was housing. While Luisa’s daughter, three years older than Maliek, didn’t have the same issues, Luisa says the combined financial and emotional strain of raising the two kids on her own was “overwhelming.”

“I was young, the [kids] would be in my face and acting crazy, and I would just want them to please go away and play,” she says. She thinks she was “in denial” about Maliek’s speech problems. Sometimes, she recalls, she felt like "giving up."

These are the sorts of situations that scholars agree put young children at grave risk of trouble later in life. Raised in environments full of economic, emotional and psychological turmoil, these kids are less likely to succeed in school or at the workplace, and are more likely to run afoul of the law or experience a variety of mental and physical health problems. But Luisa didn't give up. Acting on advice she got from her sister, she instead reached out to Child First -- a Connecticut-based organization that seeks to help distressed families, particularly those in low-income communities.

Child First is a “home visiting” program, which means staff members work with families mostly in their homes rather than in office settings, sometimes meeting as frequently as three or four times a week. The first priority is addressing tangible problems like poor housing or lack of medical care, which sometimes means connecting families with public programs. But the main focus is improving relationships within the family, particularly between the parents and children, through a combination of advice and therapy.

“People are most comfortable and most themselves at home,” says Flora Murphy, a Child First mental health clinician who worked with Luisa. “It’s most effective too for working with children. You bring children into an office setting, they’re nervous and they’re really not themselves. And it’s really not an [ideal] place to do what we need to do, which is work with families.”

The visits with Luisa’s family lasted about 18 months and ended last year. Today, signs of improvement are evident. Maliek’s eczema is under control, thanks to a program that Child First found through the University of Connecticut. He’s also enrolled in a special education program and sounds more and more like a typical 4-year-old -- still relatively behind in his speech development, but with a rapidly increasing vocabulary. Luisa works as a nanny for her sister’s kids, and that has helped her to stabilize both her financial and housing situations. "I’m paying rent, I’m paying my bills, my household needs are getting taken care of," she says.

Luisa's also learned a lot about being a parent, starting with the importance of patience and making sure her kids know that she loves them. “My patience was extremely low, dealing with the kids, and we worked on that,” Luisa explains. “I’m just this brand new person ... I understand them.”

A New Way To Fight Poverty

Nobody can know how Luisa and her kids will be doing in a few years, or precisely what effect Child First had on their lives. But many researchers believe that such early, tenative signs of progress are emblematic of what a new federal anti-poverty initiative can ultimately achieve with enough time and money -- and maybe some more judicious management from Washington.

That initiative is the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, through which Child First gets funding. MIECHV, which officials refer to as “mick-vee,” began as a pilot initiative during the Bush administration and became a full-fledged program in 2010, when the Obama administration tucked funding for a massive expansion into the Affordable Care Act. The program is popular on Capitol Hill, with prominent supporters in both parties, and Congress just renewed it for another two years.

Very few people noticed that vote, because the appropriation was part of the high-profile, controversial bill that permanently adjusted Medicare payments for physicians. But if home visiting is successful on a large scale, it could prove transformative. While paying trained nurses and social workers to visit homes can get expensive, at least in the beginning, it can also yield large returns later on -- in the form of a more productive workforce, as well as taxpayer dollars not spent on treatment for mental and physical health problems, public assistance and the criminal justice system.

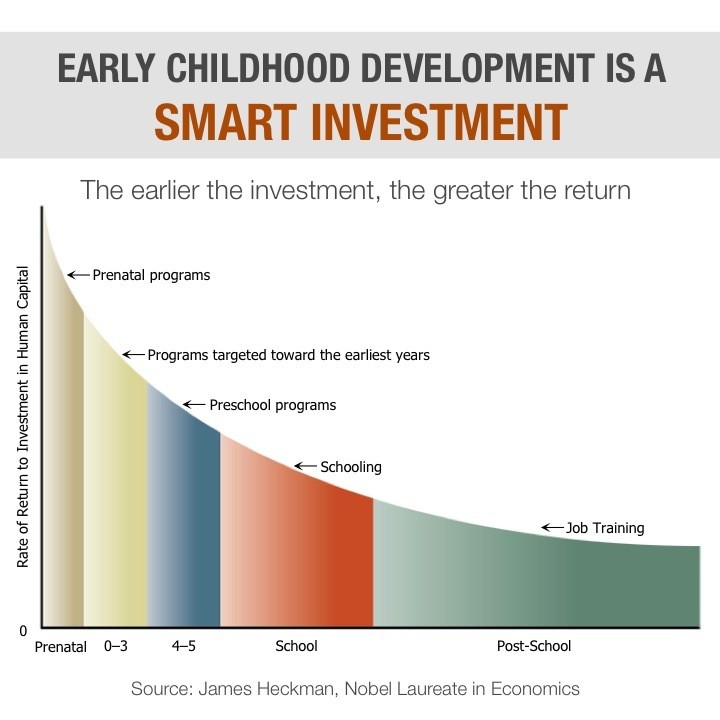

“Investing early is going to be a lot better than investing late,” says Ezekiel Emanuel, a vice provost at the University of Pennsylvania who championed home visiting while he was an official in the Obama White House. It's an argument the president himself has made on many occasions, frequently citing the work of James Heckman, the Nobel-winning economist at the University of Chicago.

Source: The Heckman Equation

MIECHV is not just an experiment in social policy. It’s also an experiment in how to manage a complicated, potentially costly federal program. The Department of Health and Human Services administers MIECHV. By law, it must distribute most of the funds exclusively to local- and state-based programs that can demonstrate through data that they are actually reducing domestic violence, improving health outcomes or having some other positive effect on the people they serve.

That requirement is part of a broader effort to link government spending with statistical evidence of what actually works. So far, HHS officials say, the agency has approved fewer than half of the programs that have applied for funding. But some prominent critics think HHS should be giving these programs still more scrutiny, not to mention ongoing monitoring.

As it is, even some of the most promising initiatives, such as Child First, still have only limited data on their long-term impact. The early results look good, experts say, but only additional research can prove how permanent the changes are.

An Antidote For ‘Toxic Stress’

The scientific basis for home visiting is a realization, based on decades of research, that the very first few years of life play a critical role in brain development.

The scientific debate has come a long way since the days of nature versus nurture -- when researchers argued over whether genetics or the environment determined ability. Today, most scientists accept that both factors matter. Genes provide the blueprint for smarts, skills and sensibilities, but experiences determine how the body interprets that blueprint -- and early experiences seem to matter the most. It turns out that physical abuse, emotional neglect and other forms of prolonged adversity for infants and babies can have more profound and long-lasting effects than scientists previously realized.

The reason is physiological. When babies are in distress, mild or severe, their bodies respond by releasing hormones that prepare the body for external threats -- by increasing blood flow to muscles, for example, or heightening awareness. This stress response is a product of evolution; it’s what protected early humans from exposure, hunger and animal prowlers. When these hormones in young children rise only intermittently, as a response to occasional stimuli and in the presence of nurturing caregivers, they are harmless and even useful. It’s how children first learn to calm down, to show patience and to overcome new challenges.

But when adversity persists and when loving adults aren’t around to provide comfort or care, the hormones remain at elevated levels. Over time, they can distort and stunt development of brain matter, going so far as to interfere with the way a child’s body translates its own genetic code into new neural pathways.

Scientists have a name for this. They call it “toxic stress” -- a phrase made popular by Jack Shonkoff, director of the Harvard Center for the Developing Child.

“We think of mercury and alcohol and lead as toxins to the brain -- they damage the brain, they poison the brain,” Darcy Lowell, a founder and chief executive officer of Child First, explains. “Well, this kind of stress does just that.”

Addressing or reacting to those problems later in life is extremely difficult, not to mention expensive. (According to the Vera Institute of Justice, the average cost of keeping somebody in prison is about $31,000 per year.) But, as the journalist Paul Tough has chronicled in his work, several early interventions have shown promise. And for the last few decades, one intervention in particular has captured the imagination of social policy experts.

An Experiment That Worked

In the late 1970s, a developmental psychologist named David Olds started a home visiting program. Its original inspiration -- according to an official history produced by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation -- was the frustration Olds felt years before while working at an urban day care center. He realized that many children had already developed serious intellectual and mental problems, even though they were still relatively young.

Olds became convinced that acting early and targeting first-time mothers, ideally while they were still pregnant, could help teach parenting skills that many of these young mothers had never learned firsthand -- all while connecting both mothers and their children to the services they might need to get by on a day-to-day basis. It was, he thought, the single best chance to stop the cycle of poverty in its tracks.

Olds eventually got funding to try a randomized experiment in Elmira, New York, and the results were dramatic. Within two years, Olds found, the incidence of child abuse among families in the program had plummeted relative to the incidence among families that were not in the program.

Subsequent experiments yielded similarly impressive results. Over and over again, the families that got home visitors had fewer medical problems, higher participation in the workforce and lower reliance on public assistance, as well as increased use of birth control and spacing of pregnancies. As public health experts have long known, delaying a second pregnancy can make a huge difference for young single mothers, increasing the likelihood that they will be able to find a sound financial footing and create a stable home for their kids.

Most impressive of all, perhaps, was that the effects seemed to last. Follow-up studies on the experiments that Olds conducted showed that reliance on public assistance among participants was down while labor force participation was up, the incidence of child abuse and neglect had fallen by nearly half, and run-ins with the criminal justice system (getting arrested or getting convicted) had declined by around two-thirds.

In 2003, Olds helped to establish the Nurse-Family Partnership, a nationwide, nonprofit organization that has operations across the U.S. and remains the gold standard for home visiting programs. Subsequent publicity, including a widely read dispatch by Katherine Boo in the New Yorker, encouraged states to start home visiting programs of their own. The program really took off in 2010, when the Obama administration and its allies created MIEHCV. Thanks to $1.5 billion in funding over four years, administration officials say, the number of home visits nationally has tripled.

‘The Hardest Cases’

Child First has its own data to back up claims of success. Studies have shown that participation in Child First reduces the incidence of developmental problems and mental health issues for children, and decreases calls to child welfare authorities. (From a research standpoint, such calls are a good proxy for abuse and other problems in the home.)

Most of the data on Child First is short-term because the program has not been around as long as the Olds initiative, and thus it hasn’t been able to track participants after they leave. But one study, also based on calls to child welfare authorities, provided strong evidence of long-lasting effects. Lowell, who is also a pediatrician and clinical professor at Yale Medical School, says she hopes funding for more long-term research will become available soon.

One distinguishing factor of Child First is its focus on what staff call “the hardest cases” -- the families that face multiple, serious challenges. One such case involved the family of Cynthia Gentry. Gentry was atypical in some respects -- she was older and had a college education, as well as a steady, well-paying job at a local hospital. But one of her children had severe mental health problems, with outbursts of violence, and a younger sibling was showing early signs of similar issues. That younger sibling had developed a series of nervous tics (including biting his fingernails nearly completely away) and was creating so much trouble at day care centers that the operators were expelling him. Gentry, like Luisa Citron, says she felt “overwhelmed” and was ill-equipped to deal with such problems.

“I’m a little rough around the edges, and I don’t take crap,” Gentry explains now. The Type A mom was very successful at work, but her personality, she admits, wasn't always ideal for dealing with her children's mental health issues.

Murphy, the same case worker who helped Luisa Cintron, got involved with Cynthia’s family. At times, she was speaking to Gentry almost daily. She would help Gentry to understand why her kids were acting the way they were, and then suggest strategies for dealing with outbursts. “Flora would give me scripts,” Gentry says.

By the time the sessions were done, Gentry explains, she’d learned to be more patient and nurturing -- very much in keeping with Child First’s emphasis on building stronger attachments between children and their caregivers.

As with Luisa, the early results seem promising. Her younger son has shed many of his tics, and he’s been in the same school for two years -- even winning a “star student” award, Gentry notes.

“If the Child First program wasn’t introduced,” Gentry says, “I probably wouldn’t be working today. I probably wouldn’t be able to provide for my family. I’d probably be pulling my hair out. I’d be bald. … I wouldn’t be able to parent. I wouldn’t be able to hold it together. You talk about dysfunctional -- we would be beyond dysfunctional.”

The Challenge Of Scaling Up

The challenge with most promising anti-poverty programs is finding a way to “scale up.” A pilot version typically starts under favorable conditions, crafted to precise specifications and administered by people heavily invested in its success. Attempts to replicate that success -- by the private or public sectors -- inevitably spawn programs that must operate under different conditions from the original, with management from people who may not know (or care) as much about what it takes to make the programs work.

Critics have said this is the problem with Head Start, the education program for young children that the federal government launched in 1965. Head Start programs now operate all over the country, serving more than 1 million children each year, but they have not been able to produce the kind of significant, long-lasting effects that the original model programs did.

Architects of the federal home visiting program were aware of this hazard. To combat it, they insisted upon scrutinizing the local initiatives that apply for funding, asking most of them to provide data. The problem -- as Sabrina Tavernese noted in a recent New York Times story -- is that HHS has pretty broad discretion over the process. The agency gives out money to programs based on a variety of goals, including things like better reading skills or reductions in domestic violence, and programs don't have to meet all of them.

Critics like Jon Baron, president of the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy, worry that HHS has made it too easy -- in effect, giving prospective grantees so many different options for demonstrating progress that virtually any program was bound to satisfy at least one criteria.

Baron didn't oppose reauthorizing the federal home visiting program. On the contrary, he gave testimony urging Congress to provide more funds. And while ultimately the best solution might be to modify the legislation, he told The Huffington Post, in the short term HHS could make a big difference simply by tightening the requirements.

“It is, on the plus side, one of the very few federal programs where evidence really does make a difference in grantmaking decisions, in determining which programs get funded," says Baron. "But there’s a loophole in the evidence standards and it’s not trivial. It’s allowed models not backed by good evidence, and in some cases negative evidence, to nevertheless qualify as evidence-based.”

HHS officials say the funding review process weeds out low-performing programs, and point to the fact that many initiatives do not receive funding.

“HHS believes the home visiting program has undergone a great deal of scrutiny and the data bears out early results,” says Samantha Miller, an agency spokesperson. “That said, we are always looking for ways to improve the home visiting program, and as our evaluation continues we will remain flexible and responsive to the needs of the states and most especially the mothers, children and families they are serving.”

Even with more rigorous assessment, of course, not all initiatives are going to work all the time. Families that go through the Nurse-Family Partnership or Child First still face plenty of challenges and setbacks; both Luisa Cintron and Cynthia Gentry described having “bad days.” And in many instances, the children whom these programs touch still have problems, sometimes severe problems, later in life. But if home visiting can’t end poverty or the problems associated with it, advocates and experts say it can make a substantial difference -- in ways that benefit not just individual families, but also society as a whole.

“There’s so much poverty, and so much trauma, and so much adversity in the lives of so many families nowadays,” Lowell says. “If we give them the right kind of help, we really believe they can thrive. They can be smart, and excel, and be creative, and add to our population and to our culture. These are families that have so much potential. We need to do the right thing.”