/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34208805/3067024984_9d8fdde683_o.0.jpg)

The world's animal and plant species are going extinct at a rate 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than they did before humans came along. If trends continue, we could lose one-third of all species by the end of the century. A variety of birds, frogs, fish, mammals — gone.

Those grim statistics come from a big June 2014 study in Science, led by Duke University biologist Stuart Pimm. The paper was the most comprehensive attempt yet to calculate a "death rate" for the world's species — an update on work first begun in 1995.

It's not an easy calculation to make: we still haven't fully tallied all the current species on Earth, for instance. So the researchers had to make estimates on how many species there are likely to be, how many are dying off, and what that "death rate" likely was before humans ever arrived on the scene.

Based on updated research, Pimm and his colleagues estimated that, before humans showed up, roughly 0.1 out of 1 million species went extinct each year. That's the "background rate." But nowadays, thanks to deforestation, habitat loss, and other factors, the "death rate" has increased to an estimated 100 to 1,000 extinctions per million species-years.

That's a big deal. And, not surprisingly, many of the media reports on Pimm's paper underscored that the Earth is now facing a "sixth extinction" comparable to the five earlier mass extinctions in history.

When I called Pimm, however, I was surprised that he wanted to emphasize the more optimistic aspects of his research. By assembling data on exactly what species are endangered and where, he said, scientists can now do more than ever to help conservation groups fend off extinctions. One example: more detailed research on Brazil's rainforests can give people an idea of which tracts are actually most cost-effective to protect.

"If trends continue, then yes, we are going to lose a large fraction of species," Pimm told me shortly after his paper came out. "But what the paper is about, mostly, is ways in which we can avoid that." Our full conversation is below — on what we know about extinction and how technology can help avert catastrophe.

The red-crowned Amazon (Amazona viridigenalis), also known as red-crowned parrot, green-cheeked Amazon, or Mexican redheaded parrot, is an endangered Amazon parrot native to northeastern Mexico. Heather Paul/Flickr

Brad Plumer: Let's start with some basics. How do we actually know how many species are going extinct — and how do we know whether that rate is high or low?

Stuart Pimm: For a long time, we didn't really have a good way to measure this. So what my colleagues and I did in 1995 was come up with this metric — extinctions per millions of species-years. It's a death rate.

What we do is keep track of which species are going extinct. We have all these people keeping an eye on birds and amphibians and mammals — and we have a pretty good idea of when they wink out.

Now the most difficult part of this is figuring out how fast species should be going extinct, based on what we know from the past. So we look at the fossil record. We know how long species lasted in the geological past. We also know a lot these days about how species come and go from their molecular phylogenies. We have a huge amount of DNA data on species we can analyze to work out what a typical time course for a species is. That tells us that species are born and die on a time scale of millions of years, rather than hundreds or thousands of years.

And what we concluded was that a typical "background rate" is about 0.1 extinctions per million species per year. Meanwhile, we're currently seeing hundreds of extinctions per million species per year. So current extinctions are about 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate.

BP: What are the big uncertainties in these calculations? We still haven't even discovered all the species on Earth today — isn't that a problem?

SP: We have to estimate, and we can estimate some things well and some things not so well. A good example is plants. We currently have discovered and named about 300,000 flowering plants. And we have a number of ways to estimate how many are missing.

For instance, you can look at the rate at which taxonomists are describing new species — and they're not describing them at the rate they used to 50 or 100 years ago. That's telling us that the pool of undescribed species is diminishing. And the fewer undescribed species there are, the harder it will be to find new ones. So we estimated, for instance, that another 15 percent of plant species are still to be discovered.

Another thing we can do is predict where those species are likely to be — they're likely to be in places like New Guinea. And they tend to be in places where there's a lot of deforestation, a lot of habitat destruction going on. And that tells us that those species we still don't know are likely to be rare and in trouble and endangered.

BP: So extinction rates are higher now that humans are around. Why? What are we doing?

SP: There are four big factors here. The first one, which is overwhelmingly important, is habitat destruction. We're destroying the habitats where species are. About two-thirds of all species on land are in tropical rainforests — and we're shrinking those rainforests.

In the Americas, the greatest numbers of species on the brink of extinction are in the coastal forests of Brazil and the northern Andes and Ecuador. If you look at the coastal forests of Brazil, east of Rio de Janeiro, something like 95 percent of all forest has been destroyed. So it's not surprising that that part of the world has an unusual number of endangered species.

Amazon, Brazil, Vicinity Rio Branco. Universal Images/Getty

Second, we're also warming the climate, and as it gets warmer species either have to move toward the poles or up mountains. This could be a big one in the future.

Third, we've been incredibly careless about moving species around the world. I'm in the Florida Everglades, where there are an obscene number of Burmese pythons slithering around, which cannot do any good. So invasive species is a third.

Finally, particularly in the oceans, there's just overharvesting. We've depleted the oceans by fishing and more fishing and yet more fishing, and driving species to the very brink of extinction.

BP: The historical record shows there have been five mass extinction events in the Earth's history. And lots of people keep suggesting we're on the verge of a sixth. But what are the criteria for this? How would we know?

SP: I'm actually not a big fan of the term "sixth extinction." But we are certainly seeing a highly accelerated rate of extinction.

If that continues — and continues for many decades — then by the end of the century we are going to lose one-third or one-half of all species. And that kind of loss in biological diversity hasn't been seen in 60 million years. The last time we lost that many species was when an asteroid plowed into the Yucatán in Mexico. So if trends continue, then yes, we are going to lose a large fraction of species.

But what the paper is about mostly, is ways in which we can avoid that. Yes, it's bad, but the paper is full of important news about how we can make a difference.

BP: Let's talk about that. What are ways to avoid — or at least mitigate — mass extinction?

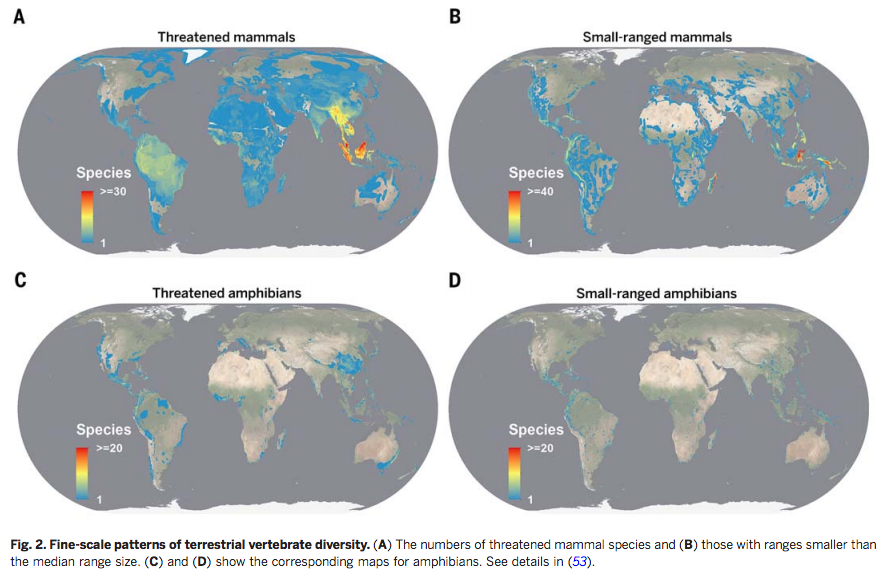

SP: First of all, most of the paper was about where species actually are and where the vulnerable species are. We have really good maps now showing where a lot of species are, on land and in freshwater and the oceans. We can identify the key places that matter:

Map of threatened mammals and amphibians:

Pimm et. al. (2014)

One of the places we find hugely important is the coastal rainforests of Brazil. It's an area that's 1 million square kilometers — the size of California, Oregon, and Washington.

And in that area, there are large numbers of threatened species, because it's a tropical rainforest and massively deforested, and the species that remain are in these little forest fragments. But now we know with increasing detail which fragments. And we have the science to know that more fragments will lose more species and we'll lose them faster.

BP: And that information is useful for conservation?

SP: Yes — it gives us a practical solution. What my NGO, Saving Species, does is we take our data and identify exactly where we think the most important fragments are. And then we raise money from Brazilian conservation groups to buy up the land between the fragments and reforest it. So we reconnect it — stitching habitat fragments to form much bigger habitats.

And often it requires very modest purchases of land. East of Rio de Janeiro, for instance, it only required a few hundreds hectares to stitch together a piece of forest that's 8,000 hectares. And in doing so, it had huge impact on a charismatic monkey called the golden lion tamarin. That came about from using very focused science to identify the key areas and understand the key processes, and going in there and working with local communities.

BP: Are there similar projects elsewhere?

SP: Yes, there are projects in Madagascar, projects in the Northern Andes. We're hardly the only people trying to do conservation. If you look at what the world is doing, it's protecting a lot more of the planet than it has in the past.

But those conservation efforts aren't always the places that are optimal. Some places are bad. We need to encourage people to protect the places that matter — using scientifically informed decisions.

BP: Are there other ways new technology or research is helping conservation?

The orange toad that Stuart Pimm identified and uploaded to iNaturalist.

SP: We do have an extraordinary piece of technology for surveying biodiversity — it's called a smartphone. A few years ago, in Brazil, I was hiking through the forests, and I came across a bright orange toad about half an inch long. I had no idea what it was, and I got the GPS location for it and uploaded it to an app called iNaturalist (see right). I'm not a frog expert, but there are a lot of passionate frog people to help identify it.

That kind of information is becoming hugely useful. And there are millions of people who participate in those crowdsourced efforts. There are people in Florida Keys who go out and compile checklist of fish. There is an international community passionate about frogs. And birdwatchers. So we can engage the public in a way to have a much better understanding of where biodiversity is, where species are, and where they're moving to with global change.

BP: How does climate change complicate those conservation efforts?

SP: We know that as it gets warmer, species will have to move either toward the poles or up the mountains. And in many cases they'll have less room. So one of the concerns is that with sufficient global warming, species will lose geographical range. And that's if they can move.

There are ways to address that. The project in Brazil I mentioned, with the golden tamarins — by reforesting a connection and building a corridor in an isolated patch of forests, we also allowed certain species to move upslope (see right).

Again, it would be better if we weren't warming the planet so fast. But given that's happening, the best you can do is design your protected areas so that species have a chance to move.

BP: You also mentioned invasive species as another driver of extinction. Have there been any advances in how to deal with that issue?

SP: That's not pretty. It can be extremely hard to get rid of an invasive species once it's there. The Burmese pythons in the Florida Everglades are a case in point. This is a snake that appears to now be quite common. It's a generalized predator. It's having a big impact on wildlife population there. It captured the public's imagination because it can be a huge snake. But the reality is that we have been very careless in moving all sorts species around — plants, animal, fish. And they are a leading cause of extinction.

The best approach is to not move them around in the first place. Once they've arrived, you have to act very, very quickly to eliminate the population. But after that, it's just control — and sometimes that control can be essentially impossible.

BP: It seems that a lot of existing laws — like the Endangered Species Act — tend to focus on individual species. Does that approach still work in a world in which lots and lots species are going extinct at an accelerated rate?

SP: I'd say things like the Endangered Species Act and conservation biology have been very successful. Current extinction rates are high, but they'd likely be worse without the work of conservation biologists.

The Endangered Species Act in particular has a lot of success stories there. Bald eagles are now breeding again in every state. In the Florida Keys, 4,000 peregrine falcons will fly over Key Largo — there was once a time where the falcon was almost extinct in the eastern United States. Gray whales were once eliminated in the Caribbean and reduced to low levels in the Pacific, but they've now recovered and are a major source of tourism. So there are lots of success stories.

These efforts often don't just focus on a single species. I work on a very obscure bird in the Florida Everglades called the Cape Sable sparrow. But it's not about the sparrow, it's about water deliveries to Everglades National Park and about restoring the natural ecosystem processes to that park. It's usually a matter of the species and the ecosystems. And the species are the poster child.

The work we're doing in Brazil, we use the golden lion tamarin as a mascot, as our icon. But we picked those areas because we're pretty certain there are more endangered birds and mammals and butterflies and just about everything than anywhere in the Americas.

Likewise, in a project we're doing in Colombia, we're using the olinguito — this animal that was only described last year. It's this adorably cute little mammal, and the only pictures come from our projects. But we also know this is an incredibly rich place with a dozen of amphibians and reptiles that are new to science, lots of new plants. So yes, we tend to use single species as icons, but it's nearly always much deeper than that:

The olinguito. (Mark Gurney)

BP: Are there other ways in which thinking about conservation might have to change?

SP: I think the main story of 30 years of conservation biology is that we know how to do an extraordinarily good job. The main thrust of this paper in Science is that we are getting increasingly good information about where to act.

So if we're going to massively reduce extinction rates, we need to know where to focus our actions. We can't save everything. There are 7 billion people on the planet. But we can focus our efforts on key places. And we need to know where those key places are and act accordingly.

Do we need more resources? Yes. Do we need to focus more on the places that matter? Yes. But it's not as if we're blundering around not knowing what to do. I think the conservation profession now is very sophisticated, very clever, and has a lot of different techniques. We just have to be smart; we have to focus our energies. We have to solve difficult problems.

BP: What are the difficult problems in conservation?

SP: Quite generally, the problems are that species are going extinct typically in developing countries. So how do we engage countries like Colombia or Brazil? So we have to start thinking about this in an international context. There are complex global connections.

A good example: Brazil used to be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions from burning its forests. But with a bilateral agreement from the Norwegian government, Brazil has massively reduced its deforestation.

There's also the reality that wherever you work, whether you're working the Florida Everglades or in Madagascar or Colombia or Brazil, you have to engage local people.

In Africa, there's a project called the Big Cats Initiative that funds projects to try to minimize wildlife-people conflict. If you have cattle or goats in Tanzania and Kenya, that's your entire wealth, and if you bring your livestock into protection at night, called bomas, and if the lions break in and kill your cattle, you take that badly. So it's not surprising that people retaliate and kill those lions. We're working with National Geographic grantees to build better bomas, to enable people to protect their livestock more effectively and not retaliate.

There are a lot of those types of local issues. Like politics, conservation is local, and you have to give people an alternative path that's sustainable.

BP: What still needs to be improved on the science side?

SP: Knowing where to act is vital. The main thrust of our Science paper was that there's now a confluence of different technologies coming together in an exciting ways.

We can map out where species are. We can also figure out where they're not likely to be because we've got increasingly good data on deforestation from Joe Sexton's research group at the University of Maryland. We know where forests are being cut, we know where the protected areas should be. That puts us in a position to be very much smarter about how and where to do conservation.

But we're still missing a lot of species, and we clearly need a better idea of where many species are — though I think new technologies are going to greatly improve our ability to do that.

We're also still struggling with the overarching political question of what sort of planet we're going to hand to our children and grandchildren. That's a difficult one — it's obvious on global warming, but it's broader than that. I think this is a global debate about how we shape our global future — whether we want to have a planet that will continue to get hotter and hotter and hotter, whether we're going to use resources on land and oceans unsustainably, whether we're going to allow this wave of extinction to deplete the diversity of life on earth. That's a global issue, and I do worry about how poorly we are grasping this.

Transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Related: Elizabeth Kolbert talks about her recent book, The Sixth Extinction