Munzer Khattab likens German bureaucracy to a game of snakes and ladders. When the 23-year-old from Latakia on the Syrian coast arrived and registered in Berlin last year, he was given the address of a job centre in another part of the city. But when he turned up at the address, the building was shut for renovation. He eventually stumbled into the replacement office by accident two weeks later.

“In Syria, there was always a way to avoid bureaucracy, even if it meant paying a bit of extra money. Here, there is no way around the paperwork,” Khattab said.

His friend Ghaith Zamrik, 19, from Damascus, had similar problems. Upon arriving in Berlin he was told to sign eight documents, only four of which were translated into Arabic. “It was very frustrating,” Zamrik said. “Even my German friends struggle with the paperwork here – imagine what it is like for a newcomer.”

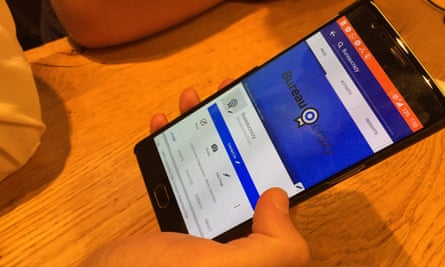

Spurred by their frustrations, Khattab and Zamrik are on a mission to simplify German bureaucracy not just for the 1.2 million people who have sought asylum there since 2013 but also ordinary Germans. Since March, they and a team of four other Syrian refugees have been developing an app called Bureaucrazy, which promises to guide newcomers and natives through the labyrinth of form filling and officialese.

The app has been developed at ReDI, a Berlin non-profit “school for digital integration” that teaches asylum seekers how to code. Bureaucrazy aims to combine three basic functions: a translation service that renders German official documents into Arabic and English, a multiple-choice decision tree for frequently encountered problems, and a mapping service that sends applicants to the right council office.

While the programme is still in development, the group is searching for coding support and financial backers in order to launch by 1 January next year. Eventually, they hope, their product could guide those arriving in Germany through everything from opening their own bank account, renting a flat, applying for a university course or registering at a job centre.

The launch of the app’s prototype coincides with the first refugee being crowned as a German “wine queen”, a tradition invented by the country’s wine industry in the 1930s. Ninorta Bahno, a 26-year-old Aramaic Christian who fled Syrian three and a half years ago, was on Wednesday crowned the regional wine queen for the city of Trier and will compete with 12 other women for the national title in September.

A spate of terrorist attacks in Bavaria had in recent weeks cast shadows over German chancellor Angela Merkel’s open-border stance during the refugee crisis.

ReDI’s founder, Anne Kjær Riechert, said she hoped projects like Bureaucrazy would help Germans to recognise that the refugee crisis had also brought immense talent into their country.

“If we want to help the people stuck in refugee camps around the world or getting trafficked, we need to empower and collaborate with people like Munzer and Ghaith. They know first hand what the situation is like, and hence can be part of building the real solutions,” she said.

Khattab and Zamrik, both of whom interrupted their studies in Syria to avoid military service, conceded that the road to the app’s completion was still long. The prototype of Bureaucrazy uses a translation service provided by Yandex, Russia’s answer to Google, though algorithms can sometimes struggle with German compounds. Compound nouns like Polizeiliche Meldebescheinigung (“a card showing you have registered with the police”) or Untervermietungserlaubnis (“sublet permit”) still send the pair into fits of eyerolling despair.

When they presented their project at the Startup Europe Summit in June, they were overwhelmed by positive feedback. “Lots of Romanians and Spaniards told us they needed a similar app. And we had thought this was just a problem for refugees,” Khattab told the Guardian.

For the app to work efficiently, Bureaucrazy would need to store information and auto-fill forms for logged-on users – a major risk, especially in a country as conscious of data security as Germany. “Germans are really into their privacy,” said Zamrik.

The developers eventually want to crowdfund their app, but are unsure of where they would keep their funds even if they managed to raise enough cash. If he puts more than €700 (£595) into his account, Zamrik said, he would get into trouble at the job centre. His applications for online banking have so far been rejected.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion