Dark matter map unveils first results

- Published

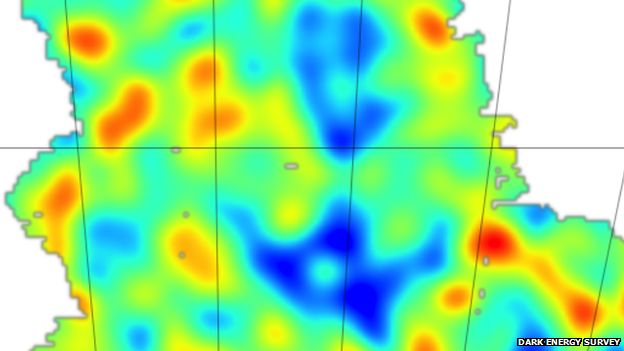

A huge effort to map dark matter across the cosmos has released its first data.

Dark matter is the invisible "web" that holds galaxies together; by watching how clumps of it shift over time, scientists hope eventually to quantify dark energy - the even more mysterious force that is pushing the cosmos apart.

The map will eventually span one-eighth of the sky; this first glimpse covers just 0.4%, but in unprecedented detail.

It shows fibres of dark matter, studded with galaxies, and voids in between.

The international collaboration, known as the Dark Energy Survey (DES), will present its preliminary findings on Tuesday at a meeting of the American Physical Society and publish them on the Arxiv preprint server.

The survey involves more than 300 scientists from six countries and uses images taken by one of the best digital cameras in the world: a 570-megapixel gadget mounted on the Victor Blanco telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, high in the Chilean Andes.

Incredible detail is required to detect dark matter, based purely on the way it warps the light from very distant galaxies.

Mapping the invisible

"Our goal all this time has been to see the invisible - to see dark matter," said Sarah Bridle, an astrophysics professor at the University of Manchester and co-chair of the DES weak lensing group, which produced the map.

"To be able to look at a map and say, 'That part of the sky's got more dark matter in it, that bit's empty,' is the dream that we've had all this time," Prof Bridle told the BBC.

"It's been a long time coming."

The survey commenced more than two years ago and will run for another three. This preliminary map was made using data from the camera's very first test images.

"We were testing out the quality of the camera," Prof Bridle explained.

"It takes a very, very long time to process all of this data and do the analysis. We're currently looking at more data and eventually we're going to have a map 30 times this size."

Even this preliminary effort is something of a landmark.

"This is the largest contiguous dark matter map that's been made," Prof Bridle said.

An earlier series of four images covered a bigger swathe of sky but the images did not overlap and had nowhere near the detail of the DES.

Subtracting interference

The business of mapmaking is complicated when the stuff being mapped is invisible and millions of light years away.

To spot dark matter, astrophysicists must pick out distortions - caused by dark matter's gravitational "lensing" of passing light - within very accurate images.

The distortions are much smaller than the warping of light by our own atmosphere, and even the irregularities added by the telescope itself. So those quantities first have to be subtracted.

"Most of the hard work goes into trying to remove those effects, to be able to uncover the gravitational lensing effect underneath," Prof Bridle said.

In the last two years, she and her many DES colleagues have measured the shapes of no less than two million galaxies within the first crop of images. And they've measured those dimensions to an accuracy of within 0.1%, which has required countless hours of heavy-duty computing.

Combining the imprint of all these minuscule distortions, the new map shows exactly where dark matter is concentrated within this particular patch of sky.

It paints an impressively clear picture, with no big surprises.

"Our analysis so far is in line with what the current picture of the universe predicts," said Chihway Chang from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. Dr Chang was one of the report's lead authors.

"Zooming into the maps, we have measured how dark matter envelops galaxies of different types, and how together they evolve over cosmic time," she said.

Stalking Einstein

Bigger surprises may come when the survey reaches its ultimate goal: testing the idea of dark energy.

Once the DES team has finished its map of dark matter, spreading its massive tendrils across the cosmos, they will be in a position to measure just how fast those tendrils, along with all the matter we can see, are flying apart.

This expansion of the universe is happening at an increasing rate, and dark energy is the force physicists have proposed to account for that increase.

"How fast the dark matter clumps together tells us about how fast the universe is being stretched apart," explained Prof Bridle.

So by comparing dark matter "clumpiness" in different ages of the universe - which we can see as different distances - scientists will be able to pinpoint the rate of expansion. And that will point to the nature of dark energy.

It might simply yield a precise measurement of this mysterious force.

Or it might go further, Prof Bridle said:

"It's also possible, with the same data, to show that dark energy is not a good theory for explaining what's going on - and in fact, general relativity itself is wrong."

The simplest theory for explaining dark energy, which is based on Einstein's relativity, she added, is "terrible" - but it is the best available.

The DES might just shake things up.

"We expect something weird to happen," Prof Bridle said.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter

- Published26 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published14 February 2015

- Published8 April 2014

- Published20 January 2014

- Published18 January 2013

- Published18 September 2012

- Published9 January 2012