The Odd Couple Fighting Against Predatory Payday Lending

In South Dakota, a conservative pastor and an openly gay former Obama campaign staffer have teamed up to battle an exploitative industry.

One of the most important bipartisan reforms of recent years started with a Twitter fight. Steve Hickey, a pastor in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, sent a letter to the editor of the Argus Leader, denouncing gay marriage and homosexuality.* Steve Hildebrand, owner of a local coffee shop, took offense. “You are becoming a huge joke in this state—huge,” he tweeted at the pastor. “We should have coffee,” Hickey responded. “I love you, tolerate you, I don’t support gay marriage.” And Hildebrand took him up on the offer: “As long as you come with an open mind and an open heart and a willingness to listen to my point of view as I was BORN gay.”

The two Steves sat down at Josiah's Coffee House and Café, the shop owned by Hildebrand. They make an odd couple. Hickey is pastor of the Church at the Gate and a conservative state legislator; Hildebrand was the deputy national campaign director for Obama’s 2008 campaign. But they soon found they had something in common: concern over payday lending. Many of Hildebrand's employees had taken out payday loans, and Hildebrand often offered them zero-interest loans to help them escape. Hickey said people in his church had often faced the same struggle. He had similarly aided people trapped in the cycle of debt that payday lending creates.

Hickey had been introducing reform bills every legislative session since he had been in the legislature. “I’ve been here five years and I’ve offered something every year, but it has never gone anywhere, but I know from polls that voters want to vote these guys off the island,” Hickey told me. At one point, payday-lending lobbyists told him they would be interested in working on legislation. They flew to South Dakota to prepare a 12-page bill. But when the bill reached the legislative committee, industry lobbyists opposed it. “They lobbied against the very bill that they wrote,” Hildenbrand told me, describing the industry as “full of bullies and lies and cheats.” Payday lending companies hired “the most powerful lobbyists walking the halls,” which “really instilled fears in the eyes of these legislators,” he said. “There’s been efforts for several years now, and you can’t even get a bill out of committee.”

The payday-lending industry tells the story a little differently. Jamie Fulmer, the Senior Vice President of Public Affairs at Advance America, which has 11 locations in South Dakota, said that while his company opposes the specific bill, “we had hoped to work for a compromise,” and that “our hope remains.” He specifically cited the bill’s stricter disclosure requirements and a “safety valve,” which offers an extended payment plan. If the proposal to cap payday lending at 36 percent passed, there is “no way any market-based lender would remain,” he said. Fulmer calculated that a 36 percent annualized rate offers lenders just $1.38 for every $100 they lend, before accounting for overhead.

With efforts at legislative reform stymied, Hildebrand and Hickey decided to take their case directly to the voters. Inspired by a similar effort in Montana, they launched a push for a ballot initiative to cap interest rates on payday loans. Shortly after they announced their plan, Republican State Senator Corey Brown put forward a bill that would double the number of signatures required to place an initiative on the ballot. Reynold F. Nesiba, the treasurer of South Dakotans for Responsible Lending, suspects that the move was an effort to keep the payday lending initiative off the ballot. “It might have been a coincidence,” he said, “but the timing sure looks suspicious.”

Other opposition was more theatrical. Chuck Brennan, a payday mogul based in Las Vegas, threatened to cancel a summer rock-and-roll festival he hosts in the state. (It was later cancelled anyway after Brennan failed to line up performers.) Cory Allen Heidelberger, the author of the Dakota Free Press political blog, suggested that Brennan had been less than sincere. “That threat was just pure propaganda,” said Heidelberger. “He was trying to turn his failure into political leverage. It was political theater.” Though Brown’s bill was eventually withdrawn, it may be the first salvo in a longer battle. “The industry is pretty profitable, and South Dakota’s a heck of a place to profit from it.” Heidelberger said. “You might see a fight here that you haven’t seen in other states.”

Payday lending is currently a $46 billion industry in the United States. About 12 million Americans borrow $7.4 billion annually from over 22,000 storefronts—roughly two for every Starbucks—across the country. The industry has come under increasing scrutiny over the past decade from critics who accuse it of being exploitative, and of trapping low-income borrowers in a cycle of debt. A nexus of federalism and money in politics have slowed reform efforts at the federal level. The much-anticipated Consumer Financial Protection Bureau regulations set to come out soon will not include a cap on interest rates. In the absence of federal regulation, advocates and policymakers are taking the battle to the state level.

South Dakota has one of the most aggressive payday lending industries in the country. Lenders there charge an average annual rate of interest of 574 percent. In practical terms, if residents of South Dakota borrow $300 to make ends meet, five months later they will owe $660. South Dakota is one of seven states, along with Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Delaware, Texas, and Wisconsin, that do not cap payday-lending rates. The trouble for South Dakota began in 1978, during the era of deregulation, when the Supreme Court decided that a national bank could charge customers in any state the interest rate of the state in which the bank was chartered. In effect, this eliminated the efficacy of usury laws, since a bank could simply move to a state with higher ceilings, setting off a race to the bottom.

South Dakota won. It eliminated its usury ceiling in 1980. Citibank, soon followed by Wells Fargo, First Premier, and Capital One, requested and received permission to charter in the state. South Dakota’s financial sector expanded rapidly, giving it the clout to press for further deregulatory measures in the 1990s and 2000s that opened the state to high-interest, short-term loans, like payday lending and car-title loans. “South Dakota pretty much reinvented usury when it invited Citibank in to do its credit operations,” Heidelberger said. The result, as Nesiba points out, is a nominally free market in loans that offers few protections for borrowers: “One does not need to be a South Dakota fisherman to understand that freedom for the northern pike in the Missouri River is not freedom for the minnow.”

The loans are tempting. Borrowers turn to payday lenders when they’re facing a short-term crunch, but often find themselves in a permanent bind. Kim B., a resident of South Dakota, is on a fixed Social Security Disability income and struggles with chronic back pain. (She agreed to speak on the condition that her last name not be used, to protect her privacy.) She took out payday loans in 2008 when her brother moved in and they couldn’t afford their medical bills. “Pretty soon I had several loans because I couldn’t afford to pay off the first loan and they would write me another loan,’” she said, “they just kept re-writing so I didn’t have to make a payment.” She finally got out of debt after two years of payments.

In 2013, when her daughter lost her job and moved in with Kim, bringing her infant son, Kim turned to payday loans again. Eventually, she had seven loans, with annual rates varying from 120 to 608 percent. She had to default in July of 2014. “I couldn’t afford to pay them back, I had loans to cover loans,” she said. Her sister tried to bail Kim out with $1,200, but it just wasn’t enough. At one point, 75 percent of her income was going to pay off her payday loans. There was “nothing” left for food or electricity, she said. “If I lose my electricity, I lose my housing, then I’d be evicted and I’d be homeless,” she said. “It took us four months to get caught up on electricity, and we needed assistance, but we were close to being homeless.”

Hickey, who has helped members of his congregation trapped in the cycle of payday-lending debt, grew frustrated watching people get rich off of exploitation. “I’ve given away thousands of dollars to pay the lenders off,” he said. One payday-loan mogul, Chuck Brennan recently purchased a $9 million second house in Newport Beach. “Good for him,” Hickey said. “I don’t mind people making money, but I feel like I partially funded that by paying the people who owe him.” He also noted that payday lenders often exploit those who are relying on government assistance, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill. “It’s an intentionally defective financial product that is deceptively marketed to the unsophisticated who are barely holding on at the margins of our society,” he said.

The experience of the two Steves is not rare. Across the country, the payday-lending industry has a vise-like grip on legislatures. A campaign to end payday lending in Montana began bringing forward “every kind of bill you could imagine” to cap interest rates, said Tom Jacobson, a Montana State Representative. But it found itself unequal to the opposition. “They were paid lobbyists and we were advocates,” explained Jacobson. “We were never once able to get it out of committee.” After 10 years of stonewalling in the legislature, advocates pushed forward with a ballot initiative to cap rates at 36 percent. The measure that couldn’t even get to the floor in the legislature won an astonishing 72 percent of the vote at the polls.

So far, payday-lending reformers have successfully fought four ballot initiative battles nationwide. In 2005, Texas voters stopped an initiative that would have allowed the legislature to exempt commercial loans from laws setting maximum interest rates. In 2008, Ohio voters passed an initiative capping payday loans at a 38 percent interest rate. In Arizona, the payday-lending industry tried to use a ballot initiative to secure its continued operation but lost, 59.6 percent to 40.4 percent. Payday lenders used their vast resources to attempt to derail these campaigns to cap limits. The National Institute on Money in Politics estimates that the industry spent $35.6 million in Arizona and Ohio to influence ballot initiatives. In Ohio, the industry spent $16 million on the ballot initiative, while their opponents spent only $265,000. In some cases, however, the industry has succeeded, primarily by keeping the issue off of the ballot. In Missouri, the payday-lending industry spent $600,000 (compared to the $60,000 raised by advocates) to successfully keep the issue off the ballot.

Payday lenders’ influence is strongest in Tennessee, where Advance America and Check Into Cash, two of the largest payday-lending corporations, got their start. Here again, money was integral to the industry’s rise. Between 1995 and 2001, payday lenders donated $250,000 to political campaigns for state legislators and the governor. Maryville College professor Sherry Kasper, who studies the state’s payday lending industry extensively, wrote, “industry members appear to have deftly converted some of their profits into political contributions to both state and federal legislators who influence the legislative debate to modify the structure of this industry in their favor.” The Tennessee Cash Advance Association donated $125,000 to various state legislators to get the Deferred Presentment Services Act passed on October 1, 1997. In 1998, when the sunset provision in the law required that it be re-evaluated and extended, the industry forked over another $22,500 in donations to House Democrats and $8,000 in donations to State Senator Robert Rochelle, who sponsored the extension.

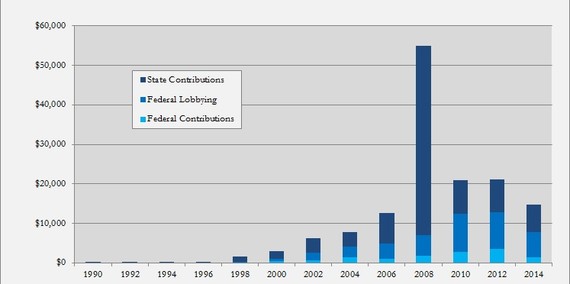

Data from the Center for Responsive Politics and the National Institute for State Money in Politics shows that the industry has spent an inflation-adjusted $143 million between 1990 and 2014. This includes campaign contributions and lobbying at the federal level, as well as state campaign contributions. There is no comprehensive data on state-level lobbying or local spending, but they would undoubtedly raise the total sum.

In addition to currying favor with state legislators, this money has been effective at the federal level. The CFPB’s new regulations for the payday-lending industry are built on extensive research into its practices. Fulmer notes that less than one-half of one percent of the complaints the CFPB has received were related to payday lending and argues that complaints against illegal lenders increase when caps drive licensed payday lenders out of the state. "They're going to have a less viable alternative, which will have a higher cost and be unregulated. In previous states that have restricted payday lending, there was a spike in complaints," he said. Melanie Hall, the Commissioner of Financial Institutions in Montana, reports that Montana’s experience, since implementing a 36 percent cap, bears out that point. “We have certainly had an increase in the number of complaints that we receive against unlicensed lenders,” she said.

While these regulations may prove welcome, the CFPB is not legally allowed to cap rates, so the debate will still play out at the state level. “It’s not going to fix the fundamental issue if it doesn’t include a rate cap,” Hickey said. Here, too, the story is tainted with money. Originally, Senator Christopher Dodd had intended for the CFPB to be able to regulate payday lending. But Tennessee’s Senator Bob Corker intervened. In the end, the body was left without independent authority to enforce regulations against payday lenders. Corker received $31,000 in donations from Check Into Cash since 2001 and another $1,000 from the Tennessee Community Financial Services Association. Corker denies that such donations influenced his decisions.

There is a broad academic consensus against payday lending. The Pew Charitable Trusts found that 69 percent of first time borrowers use payday loans to pay for regular bills, not for unexpected expense. Lenders target low-income people and people of color. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that the median income of payday loan borrowers is $22,476. Almost half of borrowers took out ten or more payday loans over the year-long period they studied. In total, the median borrower took out ten loans and paid $458 in fees, spending 55 percent of the year in debt. The industry is ripe for exploitation: 37 percent of borrowers say they would have taken a loan with any terms. These borrowers say they are being taken advantage of and one-third say they would like more regulation. Chris Morran of Consumerist notes that, “the average payday borrower is in debt for nearly 200 days.”

A recent Howard University study examining payday lending in four Southern states found that “vulnerable minority and ethnic groups and lower-income residents are disproportionately affected by the negative economic consequences of these operations.” The study concluded that the cumulative impact on the economy was modestly positive in Mississippi, but negative in Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana. A separate study of payday lending in North Carolina found that payday lenders target communities of color. Even after controlling for other factors, researchers found that “payday lenders tend to locate in urban areas with relatively higher minority concentrations, younger populations, and less-well-educated citizens.”

A 2011 study found that the payday lending cost 14,000 jobs and an economic loss of $1 billion through reduced household spending and increased bankruptcies. Economist Brian Melzer found that, as borrowers shift income to paying off loans, they are more likely to rely on food stamps and less likely to make childcare payments. Defenders of the industry claim that most borrowers are paying for one-time purchases, but the data suggest otherwise: most people borrow for routine expenses and continuously roll over their debt. The Center for Responsible Lending estimates that the high APR loans cost consumers $3.5 billion in extra fees each year.

Proponents of the payday-lending industry argue that without payday lending, consumers will be driven to even more dangerous means of lending. For instance, Donald P. Morgan and Michael Strain of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York argued that “payday credit is preferable to substitutes such as the bounced-check ‘protection’ sold by credit unions and banks or loans from pawnshops.” However, a 2007 study after payday lending was banned in North Carolina in 2001 found that “the absence of storefront payday lending has had no significant impact on the availability of credit for households in North Carolina.” For instance, the North Carolina State Employees Credit Union offers a $500 loan with a 12 percent APR—far better than the terms offered by payday lenders. Morgan and Strain analyzed bounced checks, Federal Trade Commission complaints and Chapter 7 bankruptcy. However, their data cannot support these claims. For instance, the bounced check data comes from regional check processing centers, which means that data were mixed in with states that data did have payday lending.

The experience of Montana offers a mixed narrative—in the wake of regulations on payday lending, some borrowers have turned to credit unions, but it’s unclear what has happened to others. “Montana has zero licensed payday lenders since the passage of the rate cap in 2010,” Hall noted. Jacobson rejected the industry’s claims that the ban had hurt customers. “We didn’t see any of that,” he said. “We didn’t see a spike in bankruptcies, or even in pawn shops.”

Instead, Montana Credit Unions for Community Development’s small loan program “grew 25 percent in the third quarter of 2010,” Claudia Clifford, the Advocacy Director of AARP told me. The Montana Credit Union Network also ran a small-dollar loan campaign with 14 participating credit unions. Over 18 months, they issued 3,808 small loans worth $2.2 million, with an average loan of $575. Tracie Kenyon, the President of the Montana Credit Union Network, said that the average APR for those loans was 8 to 15 percent. “We had the bill to cap the payday lending and it was our hope to provide an alternative,” she said. Though credit unions have always done small-dollar loans, “our goal was to raise awareness.” These loans often ended up benefiting the people who would normally rely on payday lending: the median income of borrowers was $24,312. Given the size of the payday-lending industry, though, it’s unlikely credit unions absorbed all the borrowers. The data I examined did not show a spike in credit union membership in the wake of the legislation.

A major problem for people trapped in cycles of debt is that they can’t access better lending until they pay off their payday loans. “The best way to get good lending is to get bad lending out of the way,” said Diane Standaert, Director of State Policy for the Center for Responsible Lending in South Dakota. She argues that the difference is the ability to repay, “There are responsible lenders making responsible loans, loans that are designed to perform and succeed in light of the borrowers situation. Payday lenders make their loans with no regard to borrowers ability to repay.”

To consumer advocates, nearly anything is better than payday lenders. But simply capping payday lending is not the end of the story, for South Dakota or for any state. Many of those who turn to payday lending do so because they lack other options. They often have no credit history or bad credit. Simply banning payday lending would ameliorate the underlying problem, but not fully solve it. The ideal way to reduce bad lending is to crowd it out with good lending.

Some states are making progress towards building good lending for disadvantaged borrowers. In California, Governor Jerry Brown recently signed a bill into law that allows nonprofits to make small loans without burdensome regulation. “The bill allows non-profits the regulatory clarity they need to offer no-interest loans of up to $2,500,” said Frederick Wherry, a sociology professor at Yale. “This range represents the loan amounts that get families into trouble with payday loans. What this law does is it recognizes that households need short-term loans, and with regulatory clarity a new group of actors can step in to compete with payday lenders.”

Payday lenders prey upon the unbanked and underbanked population, which Wherry estimates to be 7.7 and 20 percent of the population, respectively. However, the crisis is even worse among people of color, at 20.5 percent and 33 percent for Blacks and 17.9 percent and 28.5 percent for Hispanics. In addition, 54 million Americans, or the combined populations of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and the District of Columbia, are not scoreable—they simply don’t have a credit score. The unscorable population is disproportionately poor and people of color. Not being able to access credit forces them into bad lending like payday loans and forces them to pay more to rent apartments and other basic services.

There are now innovations to bring the unbanked population from the margins and help them access the necessary credit. One such program, Lending Circles, which is managed by the Mission Asset Fund, currently has 2,935 clients, and has issued $3,651,307 in zero-interest loans. The program helps unscorable people build credit by creating small groups that lend money to one another with zero-interest loans. Everyone in the circle makes a monthly payment, and one member of the circle receives the loan.

In 2016, America will elect a new president and a new Congress. Voters in many states will consider a flurry of ballot measures, many pushed by special interests. In South Dakota, a populist alliance of Republicans and Democrats could well spell the end to an exploitative industry that has trapped many residents in spiraling debt. That effort is echoed by similar campaigns in Alabama, Utah, and Idaho, three other poorer states with outsized payday lending industries. When I talked to Hickey, he was optimistic that the money and political heft of the payday-lending industry would eventually be overcome by the power of the voters. Hickey insists that payday lending isn’t a partisan issue: “I know from polls that voters want to vote these guys off the island.”