Tucked away in the Rare Book Division of the New York Public Library lies a gastronomic treasure trove of authentic New York dining menus. Dating from the early 1840s to the present day, this immense collection of 45,000 menus offers a rare taste of New York through the ages.

As the library endeavors to digitize its esteemed culinary archive, the historical significance and leading benefactress of the collection have come into focus. Astonishingly, more than half of the archived menus held by the institution were collected by a single woman, an unmarried schoolteacher named Frank E. Buttolph.

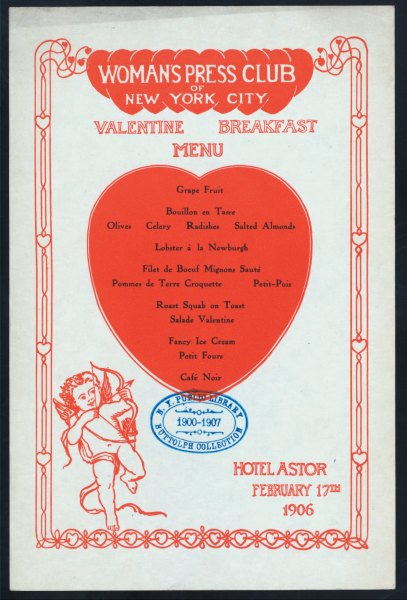

A spirited collector, Buttolph spent the majority of her 20-plus-year career as a volunteer archivist at the New York Public Library soliciting menus from restaurants, hotels and coffee shops around New York City. Her painstaking efforts to collect modern day throwaways date back to 1900, the year Buttolph donated hundreds of her personal menus to the Astor Library, a founding constituent of today’s NYPL. In return for her gift, Director John Shaw Billings agreed to give Buttolph a volunteer position as the library’s menu archivist, a role that allowed her to continue to collect menus on the library’s behalf.

Buttolph’s fascination with collecting menus—which the New York Times once attributed to her “feminine instincts for accumulation,” and for which she was largely misunderstood by a male-dominated press—led her to keep collecting until her death in 1924. By then, she had gathered more than 25,000 menus, which became known as the Miss Frank E. Buttolph American Menu Collection (1851-1930), today identified by Buttolph’s characteristic blue stamp in the library’s archives.

- Menu from Pullman Dining Car Service – Funeral Train of President McKinley, Washington to Canton, 1901. (Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

- Frank Buttolph personally stamped many of the menus in the library’s archives.(Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

And while the city may no longer boast a modern-day Buttolph running around collecting menus by the thousands, historic menus are getting a closer look by historians and the general public as a valuable category of ephemera.

In April 2011, to meet the needs of its researchers, the NYPL launched a collaborative menu transcription project called What’s on the Menu? in attempt to transition the more than 45,000 menus to a digital format.

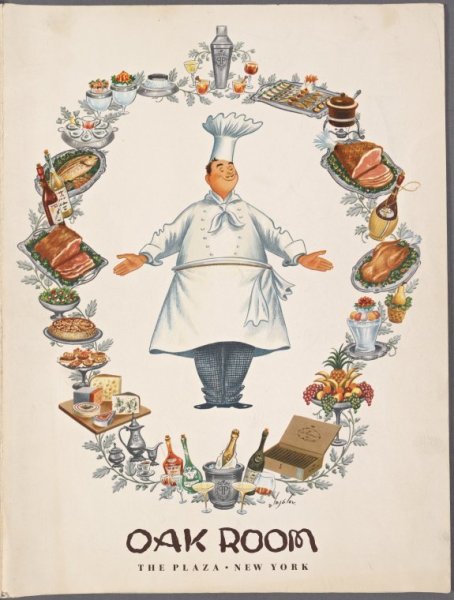

New Yorkers may now feast their eyes on digitized artifacts such as Mad Men-era bills of fare from city institutions like the Plaza Hotel and Tavern on the Green.

|

The ambitious project—spearheaded by Ben Vershbow, Director of NYPL Labs, and co-curated by librarians Rebecca Federman and Michael Inman, Curator of Rare Books—envisions an easily accessible electronic “database of dishes.”

The menu digitization project is unique in many ways, particularly for its use of crowdsourcing. In a nod to the collection’s philanthropic benefactress, the library has called on an army of volunteers from the general public to help transcribe the menus dish by dish.

To date, volunteers have already transcribed a total of 1,328,904 dishes from some 17,541 menus. Thanks to these efforts, New Yorkers may now feast their eyes on digitized artifacts such as Mad Men-era bills of fare from city institutions like the Plaza Hotel, the Waldorf-Astoria, the Hotel Pierre, and Tavern on the Green.

- Menu from the Palm Court – The Plaza Hotel, 1959. (Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

- Bar suggestions, Palm Court. (Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

What’s on the Menu? was born out of a smaller, trial venture that took only three months to successfully digitize a group of 9,000 menus for the launch of the library’s Digital Gallery, an impressive “living” image database that provides free and open access to over 800,000 images from the library’s expansive collections of illuminated manuscripts, historical maps, rare prints, photographs and more. As of this month, the Digital Gallery has been replaced by the enhanced Digital Collections database, a project that is among many similar large library digitization campaigns around the world.

According to Henry Voigt, a private collector of historic menus who maintains the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus, menus as an item emerged in the late 1830s, when service à la russe—the serving of dishes in courses—became popular with the advent of hotels and restaurants.

Back in the day, Americans dined on prestigious dishes made from endangered species like terrapin turtles, dishes of wild duck like the Canvas Back from the Potomac, umpteen different kinds of sweetbreads, and even pigeons.

|

Artistic printing—a design aesthetic that involved the use of various forms of fonts to make items more attractive—was popular in the 19th century during the Gilded Age, when big mansions lined Fifth Avenue and the wealthy of New York dined at grand banquets as a form of conspicuous consumption. In fact, Tiffany & Co. started off as a stationer long before they were ever a jeweler, operating an art department that illustrated elaborate designs on menu covers. Admired as an art form, menus were originally meant to be kept as mementos, but most failed to survive.

“What is appealing about this particular collectible is that it reflects the history of everyday life. It is what the ephemera-ists call ‘unwitting historical evidence,’” said Mr. Voigt, who writes about menus on his blog, The American Menu. “My particular enjoyment is the process of historical discovery. I really enjoy picking up these threads of history and deciphering something new about our cultural past.”

Rebecca Federman, Co-Curator of NYPL Menus, E-Resources Coordinator and Culinary Librarian at the NYLP, believes the menus appeal to New Yorkers because they offer Manhattanites a unique taste of their past. “The menus tap into people’s food memories. In general, food memories are very strong, especially memories of eating out,” said Ms. Federman. The library hears anecdotally from people all the time who, while performing genealogical searches, stumble upon menus from restaurants owned by uncles and aunts, parents or grandparents.

While the general public is mostly interested in the big name New York restaurants, those are not the menus that appeal to Ms. Federman. “I am thrilled by the forgotten restaurants and the restaurants that people wouldn’t know existed anymore,” she said. “I like more of the restaurants that everyday people would be going to on a regular basis, restaurants like Adams’ Restaurant. They give you a much better indication of what people were actually eating.”

- Menu from Delmonico’s Chamber of Commerce 123rd Annual Banquet, 1891. (Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

- Menu from Ratner’s Restaurant, 1987. (Photo Credit: Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library)

‘We thought that sushi arrived in New York in the 1960s. Then Rebecca found a menu from a Japanese restaurant on W. 47th Street called Yoshino-Ya—it was offering sushi in 1932. That menu alters the history of Japanese restaurants in New York.’

|

Currently, in order to explore the entire menu collection, a researcher needs to make an appointment to visit the Rare Book Division at the library’s Midtown branch and search through boxes of menus catalogued by year. Ms. Federman devotes part of her time to helping scholars navigate the complex archives. One researcher, Dr. Paul Freedman, the Chester D. Tripp Professor of History at Yale University, who specializes in the unrelated field of medieval history, began using the collection four years ago to research how Americans dined at high-end restaurants of the 19th century.

“I think that these menus are a vital resource because they tell you what is popular, and if you look at enough of them, you get a sense of the taste of the past,” said Dr. Freedman. “The menus show you that there are so many things that we don’t eat anymore or that we can’t get anymore.”

For example, back in the day Americans dined on prestigious dishes made from endangered species like terrapin turtles, dishes of wild duck like the Canvas Back from the Potomac, umpteen different kinds of sweetbreads, and even pigeons.

“Anybody who is curious about what people ate or how people lived in the past will benefit from the menu collection and digitization project,” said Dr. Freedman.

Laura Shapiro, a culinary historian and former columnist at Newsweek, began using the menu collection in 2010 when she teamed up with Ms. Federman as co-curator on the exhibition Lunch Hour NYC.

“Menus can be enormously revealing,” said Ms. Shapiro. “But it’s never easy to get a grip on a huge collection like this, and even now that I’m somewhat familiar with it, if I’m exploring something new I still start by talking to Rebecca. She knows the collection inside out, obviously, but she’s also good at helping people navigate it so that they not only find answers but end up asking better questions.”

Asking questions led Ms. Shapiro and Ms. Federman to new discoveries about Japanese food in New York, among other revelations. “We thought, because every source said so, that sushi arrived in New York in the 1960s. Then Rebecca found a menu from a Japanese restaurant on W. 47th Street called Yoshino-Ya—it was offering sushi in 1932. We don’t know another thing about that restaurant; it left no other trace, but we do have a menu, and that menu alters the history of Japanese restaurants in New York,” said Ms. Shapiro.

In the future, the What’s on the Menu Project? hopes to aid scholars like Dr. Freedman and Ms. Shapiro in unlocking valuable new data points. Ms. Federman and her colleagues have big plans for the menu collection. They hope scholars will someday benefit from partnerships with other libraries and the implementation of user-solicited tasks such as the linking of data. For now, food enthusiasts can enlighten their palates by exploring the newest menus on the library’s electronic database of dishes, a groundbreaking new tool for unlocking some of life’s historical mysteries.