Think about how often you check e-commerce or flash sales sites on your phone, shop while watching TV, or buy an article of clothing just because it’s cheap. Even if you don’t do it incessantly, odds are good you know someone who does.

In wealthy countries around the world, clothes shopping has become a widespread pastime, a powerfully pleasurable and sometimes addictive activity that exists as a constant hum in our lives, much like social media. The internet and the proliferation of inexpensive clothing have made shopping a form of cheap, endlessly available entertainment—one where the point isn’t what, or even whether, you buy, but the act of shopping itself.

This dynamic has significant consequences. Secondhand stores receive more clothes than they can manage and landfills are overstuffed with clothing and shoes that don’t break down easily. Consumers run the risk of ending up on a hedonic treadmill in which the continuous pursuit of new stuff leaves them unhappy and unfulfilled.

For most, breaking the cycle isn’t as easy as just vowing to buy nothing. It’s no accident that shopping has become such an absorbing and compulsive activity. The reasons are in our neurology, economics, culture, and technology.

Why do we enjoy shopping?

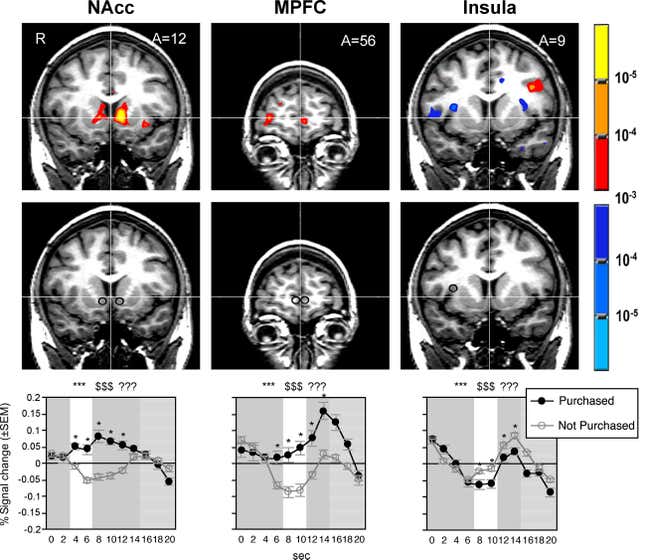

Shopping is a complex process, neurologically speaking. In 2007 a team of researchers from Stanford, MIT, and Carnegie Mellon looked at the brains of test subjects as they made shopping decisions, using fMRI technology. They found that when they showed one of the study’s subjects a desirable object to purchase, the pleasure center, or nucleus ambens, in the subject’s brain lit up. The more the subject wanted the item, the more activity the fMRI detected.

The researchers then showed the subject the item’s price. The medial prefrontal cortex weighed the decision, as the insula, which processes pain, reacted to the cost. Deciding whether to buy put the brain, as the study put it, in a ”hedonic competition between the immediate pleasure of acquisition and an equally immediate pain of paying.” The mindset is in line with evidence that shows happiness in shopping comes from the pursuit, from wanting something.

While pleasure kicks in just from the act of looking, there’s also pleasure in purchasing, or more specifically, in getting a bargain. The medial prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain that does what’s essentially cost-benefit analysis. “It seemed to be responsive not necessarily to price alone, or how much I like it, but that comparison of the two: how much I like it compared to what you charge me for it,” said Scott Rick, one of the study’s authors and now an assistant professor of marketing at the University of Michigan.

It is what’s called “transactional utility” says Dr. Tom Meyvis, a professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business and an expert in consumer psychology. “You see this a lot with clothing,” he tells Quartz. “Part of the joy you get from shopping is not just that you bought something that you really like and you’re going to use, but also that you got a good deal.”

If seeing items you want and getting a bargain both elicit waves of shopping joy, you couldn’t engineer a more pleasurable consumer culture than the modern, globalized West.

Fast, cheap, and out of control

Fast fashion perfectly feeds this neurological process. First, the clothing is incredibly cheap, which makes it easy to buy. Second, new deliveries to stores are frequent, which means customers always have something new to look at and want. Zara stores famously gets two new shipments of clothes each week, while H&M and Forever21 get clothes daily. These brands are notorious for knocking off high-end designers, allowing the customer to get something at least superficially similar to the pricey original at a small fraction of the cost, and they’re priced lower than the rest of the market, making their products feel like a bargain.

The low costs mean people can buy things they don’t need without much thought. If a $30 dress or shirt drops to $20 or $15 on sale, it’s practically irresistible. That hedonic pleasure center in your brain lights up, with the price causing little competing pain.

The only way to turn a profit selling clothing that cheap is to sell a lot of them. That’s exactly what fast fashion has been doing, and making huge profits at it. Zara cofounder Amancio Ortega is recognized by Forbes as the “world’s richest retailer.” Sweden’s wealthiest person is Stefan Persson, chairman of H&M. Both their companies continue to grow.

Mid-market and luxury brands play off consumers’ desire for a bargain as well, with many that seem to be perpetually holding sales. To facilitate the frequent markdowns they offer, several now inflate their initial retail prices. They’re able to protect their margins and let customers believe they’re getting a deal, enticing them to buy.

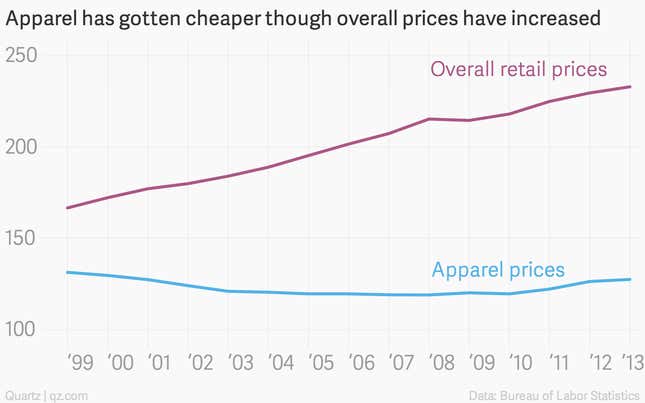

Overall, clothes have been getting cheaper for decades, ever since apparel manufacturing started moving to developing countries, where production costs are significantly lower. In the US, the world’s largest apparel market, 97.5 percent of clothing purchased is now imported, according to the American Apparel & Footwear Association. That percentage has risen steadily for years. As recently as 1991, it was just 43.8 percent.

The spread of fast fashion chains has helped spur the process. Zara, which pioneered the fast fashion model, opened its first US store in 1989, the same year that US chain Forever 21 opened its first location in a mall.

Data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, which measures the change in US retail prices, shows that while retail prices of goods overall have gone up, clothing prices have generally decreased.

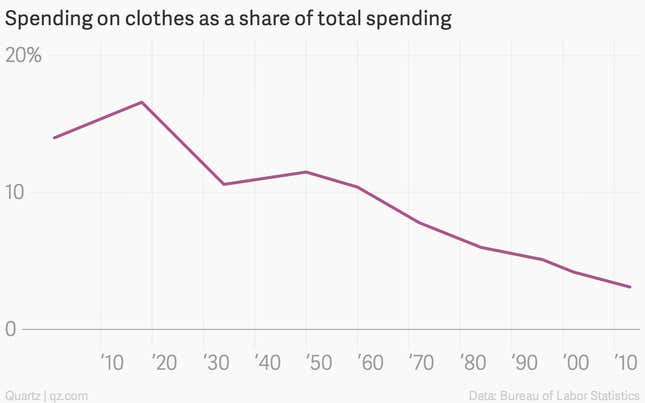

This means Americans are able to buy more clothing, and as incomes have increased overall, they spend less of their money on it.

Indeed, clothing accounted for 14 percent of Americans’ total discretionary expenditures in 1901, had decreased to 10.4 percent by 1960, and then plummeted to just 3.1 percent in 2013, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

A growing pile of stuff

These conditions make it easy for people to buy things they don’t need or even really want. One email survey of American women found that those who responded owned an average of $550 of unworn clothes; and the Council for Textile Recycling estimates that Americans throw away 70 pounds of clothes and other textiles each year.

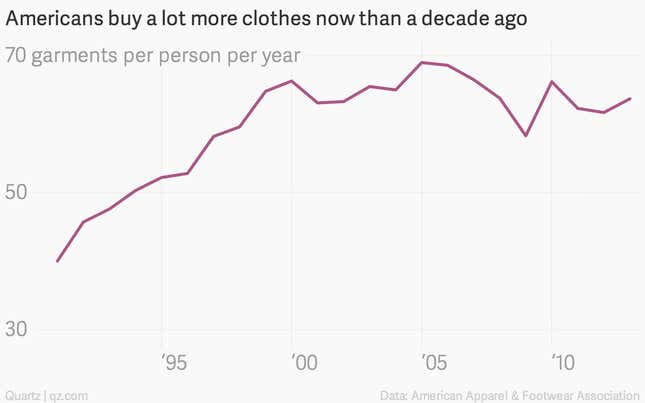

In 1991, Americans purchased an average of 40 garments per person, according to the American Apparel & Footwear Association. In 2013, it was up to 63.7 garments, down from a peak of 69 just before the recession. That means on average Americans buy more than one item of clothing each week.

The consumption isn’t by any means limited to the US. Women in Britain, for instance, now own four times as much clothing as they did in 1980.

This glut of clothing is having effects beyond stuffing our closets. About 10.5 million tons of clothes end up in American landfills each year, and secondhand stores receive so much excess clothing that they only resell about 20 percent of it. The remainder is sent to textile recyclers, where it’s either turned into rags or fibers, or if the quality is high enough, it’s exported and cycled through a cutthroat global used-clothing business.

Shopping as entertainment and relaxation

Determining exactly how much time people spend shopping for clothing isn’t simple. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics conducts an American time use survey, but clothes shopping is lumped in with shopping for everything else except groceries and gas.

It is clear, however, that more and more Americans are shopping online, and early evidence suggests they are shopping more often. Andrew Lipsman, vice president of marketing and insights at internet research firm ComScore, says that mobile shopping in particular has “exploded.”

Mobile, in fact, is now the primary way people buy online, and one ComScore study on mobile shopping in five key EU countries found that purchases of clothing and accessories led all other categories.

A forthcoming report from the firm about the way people shop on mobile found that in January 2015, Americans spent about three hours over the course of the month shopping on phones and tablets. That was up around 3 percent compared to the same period the year before, and it doesn’t include the amount of time they spent shopping on computers or in physical stores.

Lipsman points out that this mobile browsing didn’t necessarily lead to purchases. Browsing is also about research, and entertainment. ”It is more than just transactional,” he says.

It isn’t restricted to e-commerce sites either. “One of the platforms that I think is really interesting right now is Pinterest, in part because people browse it for entertainment when a lot of the content is retail content,” he says. Pinterest’s own growth has been massive. In the last six months of 2014 alone its active users grew by 111 percent.

A generation raised to shop

The obsession with looking at products, even if no purchase is intended, is especially prevalent among millennials, the generation that grew up in the age of the internet. A report by the Urban Land Institute, a nonprofit focused on responsible land use, concluded that 45 percent of millennials (called Generation Y in the report) spend more than an hour each day looking at retail sites.

“Half the men and 70 percent of the women consider shopping a form of entertainment,” the report explained. ”They are researching products, comparing prices, envisioning how clothing or accessories would look on them, or responding to flash sales or coupon offers.”

A series of separate reports on millennials reached similar conclusions: They love to shop, even if they’re not buying—although plenty are buying, too. YouTube haul videos, which feature mostly teen girls posting their scores from shopping trips, have become so popular that the bigger names, such as Bethany Mota, are now bona-fide social media stars.

A search for self

Studies of how the internet plays into compulsive buying are in their early stages, but the evidence so far suggests there may be a link. One small study published in 2009 noted a “linear relationship” between online shopping and compulsive buying. Another from 2014 of shoppers in the UK concluded that the “new shopping experience” offered by e-commerce “may lead to problematic online shopping behaviour.”

Evidence on whether compulsive shopping overall is increasing remains sparse. A 2008 study (paywall), which compared its own estimates of compulsive shopping rates in the US with those found in previous research, did suggest the number was on the rise. In the three sample groups it looked at, the study identified compulsive buying rates of 15.5 percent, 8.9 percent, and 16 percent. Earlier research estimated rates between 2 percent and 8 percent.

One of the few relevant longitudinal studies (PDF) on compulsive shopping, published in 2005, looked at the way East Germans integrated into Western society after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The study found that, as East Germans settled into Western consumer culture, they showed a “marked increase” in compulsive buying. The authors concluded that postmodern consumer societies “create an atmosphere which supports the rise of compensatory and compulsive buying.”

Dr. April Lane Benson, a psychologist and the author of To Buy or Not To Buy: Why We Overshop and How To Stop, specializes in treating compulsive shopping. When she describes the reasons for people constantly browsing as entertainment, she makes it sound like an existential crisis.

“I think that it has something to do with the pace that we live our lives at and the paucity of time that so many of us spend in pursuits that really feed our souls,” she says. “Shopping is a way that we search for our selves and our place in the world. A lot of people conflate the search for self with the search for stuff.”

Shopping becomes a substitution, a “quick fix” as she puts it, for other problems.

What should we do about this?

There has been a backlash against what some perceive as mindless overconsumption. In the past few years a “slow fashion” movement has emerged which emphasizes buying less clothing and sticking to garments made using sustainable, ethical practices.

The recent book by Japanese organizational guru Marie Kondo, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up, has led to what’s been described as a “cult” of decluttering, with her acolytes boasting of shedding piles of clothing.

The internet is also full of articles such as this one by parents trying to raise kids with non-materialistic values, as well as blogs by recovering shopaholics.

So let’s take a breath here. Residents of industrialized societies are not all doomed to endless “compensatory” shopping just because our brains seem to enjoy it and our cultures are set up for it. The five-minute break from work you take to look at clothes doesn’t necessarily mean you’re searching for your identity in a pair of pants, or that you’re trying to fill a void.

The evidence does suggest, however, that shopping has taken on a new role in our society and in our lives. It’s no longer just a transaction, a way to procure necessities or luxuries, but rather has become an end in itself. It’s a leisure activity, much like watching TV. It’s consumerism as entertainment.