In the past decade, as a percentage, more print journalists have lost their jobs than workers in any other significant American industry. (That bad news is felt just as keenly in Britain where a third of editorial jobs in newspapers have been lost since 2001.) The worst of the cuts, on both sides of the Atlantic, have fallen on larger local daily papers at what Americans call metro titles. A dozen historic papers have disappeared entirely in the US since 2007, and many more are ghost versions of what they used to be, weekly rather than daily, freesheets rather than broadsheets, without the resources required to hold city halls to account or give citizens a trusted vantage on their community and the world.

The reasons for this decline are familiar – the abrupt shift from print to pixels, the exponential rise in alternative sources of information, changes in lifestyle and reading habits, and, above all, the disastrous collapse of the city paper’s lifeblood – classified advertising – with the emergence of websites such as Craigslist and Gumtree. The implications are less often noted.

Stephan Salisbury, a prize-winning culture writer at the Philadelphia Inquirer for the past 36 years, puts them like this: “Newspapers stitch people together, weaving community with threads of information, and literally standing physically on the street, reminding people where they are and what they need to know. What happens to a community when community no longer matters and when information is simply an opportunity for niche marketing and branding in virtual space? Who covers the mayor? City council? Executive agencies? Courts?… It is this unravelling of our civic fabric that is the most grievous result of the decline of our newspapers. And it is the ordinary people struggling in the city who have lost the most, knowing less and less about where they are – even as the amount of information bombarding them grows daily at an astounding rate.”

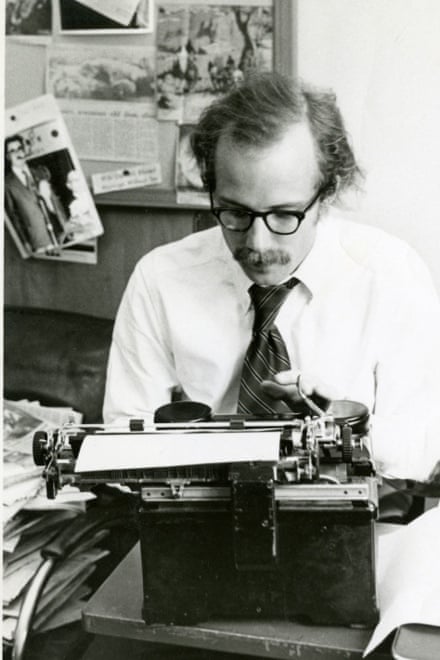

Salisbury is among the contributors to a project by a photojournalist named Will Steacy. For five years from 2009, Steacy documented the struggle and decline of Salisbury’s paper, the Inquirer, the third oldest survivor in America, as it was hit by falling sales, bankruptcy, five changes of ownership, and round upon round of staff cuts. Steacy had seen the impact of this at first hand. His father, Tom, was an editor at the Inquirer, on the news desk, then foreign, for 29 years until he was laid off while recovering from heart surgery in 2011. Steacy’s pictures bear witness not only to the quick demise of a fabled kind of newsroom culture but also to the bitter ending to a century-and-a-half in his own family history – his great-great grandfather was the founding editor of Pennsylvania’s York Dispatch in 1876; his grandfather was editor of Allentown’s Call-Chronicle in the 1960s. Will Steacy was the last of a line, as he says, with ink in his blood.

His photographs and the essays from journalists that accompany them will be published as a book next month, but first as a tribute newspaper with the Inquirer’s distinctive masthead. Journalists, as a group, rarely shy away from the elegiac, or the expression of dismay at the way things have turned out, the unfairnesses of life, but on this occasion the emotions seem justified. Steacy’s photos capture the very last knockings of a messy, creative, urgent way of life that served the population of Philadelphia with particular distinction – the Inquirer has won 20 Pulitzer prizes for its journalism in the period since 1972 when, in a move hard to imagine now, legendary newspaperman Gene Roberts resigned his job as national editor of the New York Times to become the Inquirer’s editor.

When Roberts left in 1990 the paper had 700 staff with a reputation for, as well as holding local government to account, also breaking big foreign stories – it was the Inquirer that uncovered, for example, the full truth behind the Opec oil blockade of 1973 that was causing panic in Philadelphia and beyond, by dispatching its reporters to examine the shipping lists of Lloyd’s of London and to interrogate dock workers in Rotterdam and Genoa.

The paper was housed in a grand art deco building – like Clark Kent’s Daily Planet – at the heart of Philadelphia known, with some justification, as the Tower of Truth. The presses were in the basement, and every night, it was said, their rumble would keep the powers that be on restless alert.

By the time Steacy started taking pictures in 2009 the Inquirer staff was shrinking to its current level of 210. “The Inquirer used to send reporters and photographers to South America and Africa,” he says. “They once sent a guy off to study the fate of the black rhino for six months. Now no story gets done that involves much more than a half-hour drive from the city. Otherwise it is mostly wire stories.”

In 2012, as part of the terms of its sale from a hedge fund that had saved the paper from the receiver, the Tower of Truth was sold to a developer with plans for a casino, and the paper moved into the third floor of a former department store on the periphery of the city centre.

Steacy’s camera finds symbols of that era-ending shift everywhere it looks. He approaches the old newsroom, partly designed by his father, with an anthropologist’s eye, looking for the human traces of a stubborn civilisation in retreat. These are small gestures of defiance, the pinned up cuttings and cartoons that reflect on the consequences of a revolution of “news” to “content”; there are poignant observations of defeat, note-strewn reporters’ desks quietly become sanitised and paper-free in his pictures and then disappear entirely. In the heart of the city in which the constitution was written Steacy prefaces his project with a quote from Thomas Jefferson: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government I should not hesitate for a moment to prefer the latter…”

Steacy talks to me about his work as a kind of inherited compulsion. “There is, strangely, this humble nature of the best people who work in newspapers to not want to make themselves the story,” he says. “So, ironically, it is a story that has largely gone untold.”

He embarked upon it partly to get to know something more of the world his father and grandfather knew, and which he would not know. As a boy he would occasionally come in to the Tower of Truth to meet his father after school and “run through the newsroom among these huge piles of paper like nothing I have ever seen”.

Apart from those memories, Steacy does not recall his father bringing much of his work home – allowing the mystery and mythology of what the old man did to stack up in his head. Only since his father had to clear his own desk have they talked freely about the “family business”.

“Dad was laid off before the 2012 change of ownership,” he says. “He had just had open-heart surgery. No doubt some CFO saw him as a very expensive employee in terms of health insurance. He had been there 29 years. It was incredibly painful, and that pain shifted for him toward bitterness and anger. It was me doing this project, I think, that helped him finally get through that. I found all these archives – my grandfather’s journals and so on – in the attic, and from that he opened up and was eventually comfortable talking about it.”

Steacy believes the story of metro newspapers has been a canary in the coalmine for other parts of society. “Technology can allow us to do things with greater efficiency and productivity, labour costs are reduced, but what I wanted to show is that there is a human element lost in that. We are in the middle of this huge transition, and the newspaper industry itself is very much at the front of this process that will happen in every other industry. The beneficiaries of this are a privileged and extremely wealthy few, but a broad spectrum of highly skilled workers are going to be displaced and out of luck for a very long time.”

One thing that is lost in a city like Philadelphia is another public space where people can rub shoulders on equal terms. In the Roberts era the paper sold nearly 700,000 copies in the city, it now sells just over 150,000. Advertising revenue has fallen three-quarters from $460m in the past decade. “The thing was,” Steacy says, “in Philadelphia the whole range of ethnic backgrounds, economic backgrounds, read the paper. It was the place where poor people read about rich people and rich people read about poor people. Black people read about white people and so on. It represented everyone in the city and gave them information and a voice they could trust. There was a time when dozens of eyes would read every story before it went to print. That kind of institutional integrity is in jeopardy.”

In a previous life Steacy would have wanted to be a staff photographer on a paper like the Inquirer but that job hardly now exists. He supports his wife and baby son on art projects, print sales and bits of editorial work. “Rates are what they were 30 years ago,” he says. “A photograph in my eyes is no longer worth a thousand words. Since 2000, 43 per cent of American staff newspaper photographers have been laid off. And we are in an era when 400m photographs are uploaded to Snapchat a day.”

I wonder what kinds of stories the Inquirer trades most successfully in these days?

“The stories that receive the most clicks on philly.com,” Steacy suggests “are weather stories, celebrity stories, sex stories. I guess best of all is a celebrity sex story with a good weather angle…”

Details of how to pre-order Will Steacy’s newspaper and book are available at his website, willsteacy.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion