One of the hot topics of the 2022 midterm elections is the remarkable number of Republicans running for major offices this year who have embraced some or all of the MAGA fables about the 2020 election being stolen from Donald Trump. The Brookings Institution recently counted 345 of these birds running for statewide office, Congress or state legislatures in November. The Washington Post calculates that over half the GOP candidates for the House, Senate, and major statewide officers are 2020 election deniers. This phenomenon has unsurprisingly led to concerns about the 2024 presidential election, in which Republicans appeared inclined preemptively to challenge any presidential election they lost as “rigged” or “stolen.” That was particularly true with respect to candidates for positions (e.g., secretary of State or governor) who might be in a position to certify or falsify the results in key states.

But there’s a more immediate problem this unholy host of fabulists might cause: Isn’t it likely some of them will deny their own elections if they lose?

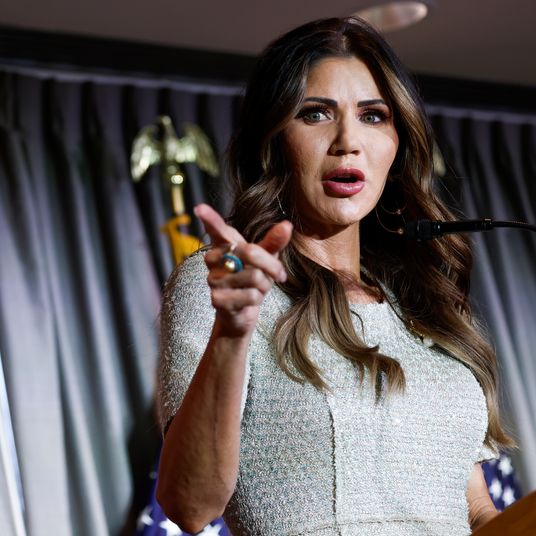

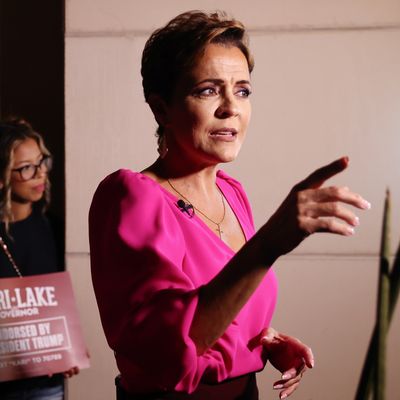

That question occurred to the Post, which asked candidates in 19 high-profile statewide races if they would accept the results of their elections, win or lose. All 19 Democratic nominees answered “yes,” as did seven Republicans. But 12 Republicans responded “no” or refused to answer repeated inquiries on the subject. They were gubernatorial candidates Kari Lake of Arizona; Ron DeSantis of Florida; Derek Schmidt of Kansas; Tudor Dixon of Michigan; Doug Mastriano of Pennsylvania; Greg Abbott of Texas; and Tim Michels of Wisconsin. Senate candidates refusing to say they’d accept the results included Blake Masters of Arizona; Marco Rubio of Florida; Don Bolduc of New Hampshire; Ted Budd of North Carolina; and Ron Johnson of Wisconsin.

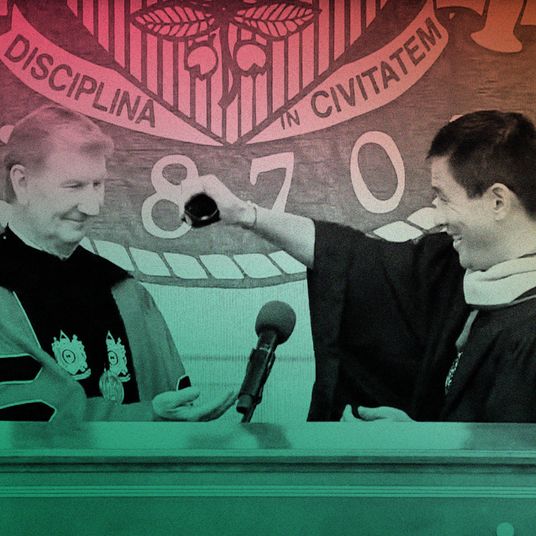

The candidates you’d most have to worry about are probably in states where Democrats control the election machinery that election-denying Republicans have been denouncing. Ground zero is Arizona, where a real election-denying ultra, Kari Lake, is opposing the sitting secretary of State, Katie Hobbs, for the governorship. Lake (and other Arizona Republicans) has been attacking Hobbs as having incompetently and dishonestly run the 2020 election (and also the 2022 primaries); the GOP went so far as to conduct a bizarre and unproductive five-month audit of the results in Maricopa County (the state’s largest, and the wellspring of recent Democratic victories). And now Hobbs is administering the 2022 election in which she and Lake are in a dead heat, with the Republican very much on the offensive (particularly after Hobbs rejected a debate challenge). It’s a recipe for another bout of Republican election denial if Hobbs ekes out a win. During a CNN interview on Sunday morning, after Lake was asked three times whether or not she would accept the election result this November, she responded, “I’m going to win the election and I will accept that result.”

And Lake won’t be alone in shrieking about a stolen election. Senate candidate Blake Masters suggested that voting machines might well add the thousands of votes to the totals for his opponent Mark Kelly. And their ticket-mate, secretary of State candidate Mark Finchem, a big-time election denier, is already planning to reject any potential loss, saying earlier this year: “Ain’t gonna be no concession speech coming from this guy. I’m going to demand a 100 percent hand count if there’s the slightest hint that there’s an impropriety.” Both Finchem and Lake have suggested voting by mail — a mainstay for voters from both parties in Arizona for many years — is inherently illegitimate.

While Arizona is the likeliest locus of a big, crazy reaction to an adverse 2022 election, it could happen in other states as well. Michigan Republicans, including gubernatorial nominee Tudor Dixon and especially secretary of State nominee Kristina Karamo, are big-time 2020 election deniers who have demonized Democratic secretary of State Jocelyn Benson. Dixon was the one candidate who answered the Post survey with an election-denying diatribe:

“In 2020, Jocelyn Benson knowingly and willfully broke laws designed to secure our elections, which directly correlates to people’s lack of faith in the integrity of our process,” said Sara Broadwater, a spokeswoman for Dixon, who is challenging Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D) and has said repeatedly that the 2020 election was stolen.

No evidence has emerged that Benson, the Michigan secretary of state, broke any laws in 2020. Dixon’s campaign added that if authorities “follow the letter of the law” this year, then “we can all have a reasonable amount of faith in the process.” She pointedly did not say whether she will accept the results.

The good news for a peaceful resolution of Michigan elections this year is that the GOP ticket to which Dixon and Karamo belong is probably going to lose by a margin too large to support an even vaguely credible challenge to the results. But look out if the results are close.

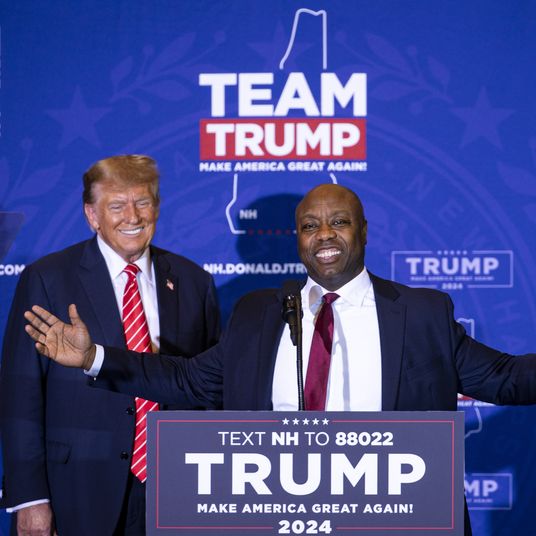

One state that is almost definitely going to have a very close set of statewide elections is Wisconsin, in which elections are largely regulated by a bipartisan Elections Commission. Unfortunately, as a byproduct of 2020 election denialism in the state, Republicans are attacking the integrity of the commission and demanding a shift in its powers to some body accountable to the GOP legislature. A familiar figure was in the forefront of these efforts dating back to 2021, as the New York Times reported: “Senator Ron Johnson, a Republican, said that GOP state lawmakers should unilaterally assert control of federal elections, claiming that they had the authority to do so even if Governor Tony Evers, a Democrat, stood in their way.” Guerrilla litigation by Republicans against both state and local election officials has become routine. And GOP gubernatorial nominee Tim Michels, a Trump protégé, has pledged to call a special session of the legislature “on day one” to “clean up the election mess.”

Do you think Johnson and Evers are going to be inclined to accept a narrow defeat in November certified by their perceived enemies? I don’t.

Now it’s true potential 2022 election deniers will need some raw material for their spanking new conspiracy theories. But that’s in the works, too, according to the Brennan Center for Justice:

At the center of this effort is the Conservative Partnership Institute, a right-wing nonprofit funded in part by Trump’s leadership PAC and home to several key former Trump aides. It is organizing a network of groups and individuals committed to taking more control of election administration in future contests.

The network has published materials and hosted summits across the country with the aim of coordinating a nationwide effort to staff election offices, recruit poll watchers and poll workers, and build teams of local citizens to challenge voter rolls, question postal workers, be “ever-present” in local election offices, and inundate election officials with document requests. The effort is an extraordinary investment in sustaining and bolstering the false narrative of widespread voter fraud.

There’s little question that more than one Republican candidate is heading toward November planning a post-election game of “Heads I win, tails you lose,” in which apparent defeat is prima facie evidence of fraud. Added to the legend of 2020’s “stolen election,” the stage will be set for a massive attack on consensus-driven democratic institution in 2024, when everyone will be playing for keeps.