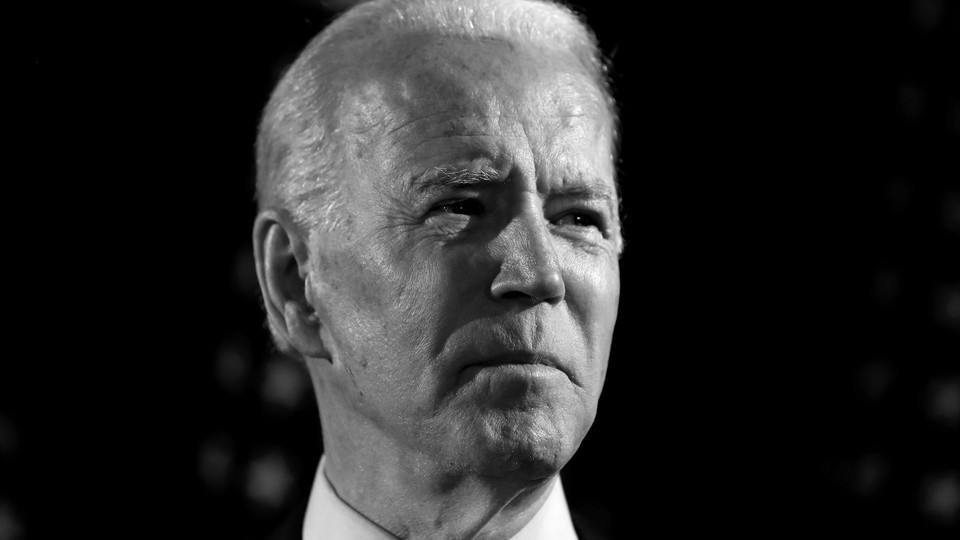

Stay Alive, Joe Biden

Democrats need little from the front-runner beyond his corporeal presence.

Two days before the South Carolina primary that would reverse his political fortunes and redirect the course of the Democratic nomination, Joe Biden’s campaign for president announced a hastily planned event in McClellanville, South Carolina. The national campaign press was alerted that Biden would enter full battle mode at this stop, that the proverbial gloves were about to come off ahead of the kill-or-be-killed primary on Saturday, and no one would want to miss this one.

And yet, when the cameras and reporters arrived, all they found were a few folding chairs in an otherwise empty parking lot, in front of a community health center. Biden walked out to a podium, mumbled a few words about the improvements he wanted to make to Obamacare, and then shuffled off, alone. The sun was shining, the birds were chirping, and absolutely nothing had changed. The most notable thing about the event was how unremarkable it was.

In the annals of political history, the week leading into Biden’s 30-point margin of victory on primary night in South Carolina will likely be recorded as the one that ultimately determined the course of the nominating battle. That Saturday night, Biden showed his unmatched power among black voters, and began to dispense with his rivals. But you sure wouldn’t have known it from the guy on the campaign trail.

Voters seem to have coalesced around Biden for his past—who they have known him to be for the past four decades in American politics—rather than for anything in his present. It’s as if Biden exists primarily as an idea, rather than an actual candidate.

Today, as the country (and the world) enters what is likely to be a prolonged period of darkness, left to the mercy of a deadly virus, Biden is grappling with the reality of what he can—and must—do in this hour of crisis, as the man who would like to take over leadership of the United States. Already, this week, there are news reports that his campaign is “in a state of suspended political animation”:

Biden can’t fully pivot to the general election. He can’t truly unite the party’s warring factions. Nor can he begin stockpiling the vast amounts of money he’ll need for November. His momentum has effectively been stopped cold.

For the foreseeable future, all live campaign events are canceled, so he can’t hit the stump to try to capitalize on the excitement he had just stoked. His ability to criticize Trump on anything other than his performance on coronavirus response and preparedness is constrained by the emergency-like conditions.

The handwringing over fundraising and campaign events may be beside the point. After all, if you were on the campaign trail for the past three months, what struck you was not Biden’s organization (there was little), or his resources (there were few), or even the campaign messaging (Joe Biden has been—and forever will be—Joe Biden). What was striking was the sense of anguish and urgency articulated by everyone, everywhere, all the time. And that was before the pandemic.

There were the Bernie Sanders supporters on the campus of Florida International University who told me, however reluctantly, that they would vote for Biden because Donald Trump had to be stopped. There were the soccer moms canvassing for Amy Klobuchar in Johnson, Iowa, who made clear that their primary concern (more than Amy’s chances) was whether Trump was going to get reelected. There were the Culinary Workers Union members in Las Vegas who hadn’t been fired up by any candidate in particular, but who told me they felt as if they faced an existential threat from the Trump administration—and that was enough to drive them to the voting booth and pull the lever. There were the older black voters in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, who woke up at 7 a.m. to check out Michael Bloomberg, mostly because they were worried that Biden was slipping, and Trump had to be removed—and if Joe couldn’t do it, they said, then they had to find someone else who would.

Almost no one I came across said they were going to vote because someone, anyone, but especially Joe Biden, had made their heart sing. Even Sanders supporters—the ones in the flesh, not online—were clear-eyed about their desire to defeat Trump, first and foremost. Ending the Trump presidency—because of the lies, the cruelty, the indignities, the misogyny, the incompetence, the fraudulence, the corruption, the clownishness, the recklessness, the lawlessness, the selfishness, oh, the list went on—that was something that united men and women across the United States and left them in a state of anguish.

On television, this concern was packaged as a focus on “electability,” but out in the country itself, it was something deeper and more emotional than that dispassionate term implies. Democrats—some independents, and some Republicans too—were terrified and furious at the prospect of another four years of Donald J. Trump. And as the weeks of the primary season ticked on, it became clear that there was one option to forestall that possibility, and his name was Joe Biden.

Through it all—the fairly awful campaign events and confusing statements and garbled debate performances—the idea of the former vice president has somehow remained consistent, and apparently convincing, as both Trump’s inverse and co-equal. Senator Bernie Sanders may still be in the race, but this is a detail. Democrats have chosen Biden as their vessel for Trump’s defeat, and that choice is the entire point: The vanquishing matters more than anything else.

In all likelihood, the desire to oust Trump will be piercing in the coming days, as death and chaos escalate. The president has been reckless, duplicitous, and morally hazardous in his leadership during a pandemic that is likely to be the defining event of a generation—forget about a campaign cycle. But the many union members looking at their closed casinos and the mothers in lockdown with their children and the students forced off their campuses and the older Americans living in complete isolation may find it impossible to imagine that their earlier fears about another four years of Trump have abated, or that the ferocity of their desire to get him out of office has lessened. Indeed, the emotion of this moment may displace any that has come before it.

Biden’s team appears to understand this, and to believe that what matters most now is keeping their candidate alive in the American imagination as an alternative to Trump. His appearances these days have an almost parallel-universe quality to them: Biden’s audience-less remarks from his home in Delaware have the suggestion of an Oval Office address, and their content seems intended to offer a glimpse into the twilight zone where someone else, someone more empathetic and capable, is president. It’s as if Biden is telegraphing to his public: You have already imagined that I can beat Trump; now imagine what it will be like when I am president.

For the foreseeable future, there will be no more speeches in front of hundreds, or lines of people waiting to shake Biden’s hand. There may not even be the glossy fanfare of a convention with a prime-time address. But, truthfully, all those things were always sort of beside the point. Like on that morning in McClellandville, and countless other ones besides, Biden was never really convincing anyone on the stump—his political power at this point is an idea, held collectively, about how to defeat Trump. The work now is to keep that idea convincing enough, for long enough, among as many people as possible, for the corporeal man to actually win.