Since 2010, hundreds of local libraries have been handed over from councils to be run by the local community. One estimate is that 500 of the UK’s 3,850 libraries are now being run by local volunteers. Despite talk about empowerment and community involvement, the reality is that local people face a stark choice: take over a local library or it faces closure.

At the Library Campaign, the national charity that supports library users and campaigners, we have seen this story played out again and again.

Local councils have seized on the volunteer idea as an easy answer to budget cuts. Each local authority has struggled to find its own solutions, with local residents doing whatever they can. The commitment of volunteers is wholly admirable, but the result is that as a country, we have been left without a coherent library service and we have seen no real attempt to find out how well community-run libraries work.

Even a recent report from the government-funded taskforce looking into the effectiveness and sustainability of community-managed libraries has been unable to draw any firm conclusions.

This is not the fault of the research team, which contacted 442 community-managed libraries of various kinds. The problem is that there is no coherent picture to find.

The new style of community-managed libraries vary wildly in what they offer, how they are staffed and financed, and how likely they are to survive. Few community-managed libraries have been around long and most have had council support for at least a couple of years.

But the nature of that support varies wildly and across the country, it’s a chaotic picture. Councils might provide some professional librarian time or none at all. In Lincolnshire, for instance, 35 community libraries share a single development officer.

Financial support could be thousands or nothing, and mightcontinue, or not. The 35 Lincolnshire libraries are to each get £5,167 a year until 2020, but no-one knows what will happen after that. They are also getting funds from all kinds of other sources. Alford’s community library, for instance, has been funded £1,000 from the local town council in its first year and £2,000 for its second year, but does not know if that will continue. No two libraries are alike, and that is just within one county.

Another example is Castle Vale library in Birmingham, which got £50,000 in funding from Birmingham city council for 2014-15 and 2015-16, part of which was used to pay city council library staff on temporary secondment. But now, although it gets a lot of support from the council, including stock, use of the council’s computer system, a van service, peppercorn rent on its building and some professional support, the library has to raise its own funds.

Councils may count these libraries as part of their provision under the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964, which requires the 151 English library authorities to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service (although there is no legal definition of what comprehensive and efficient might mean, and the government has intervened only once, in Wirral in 2009).

What does emerge is a nasty secret that few people and least of all the government talk about: we no longer have a national public library service.

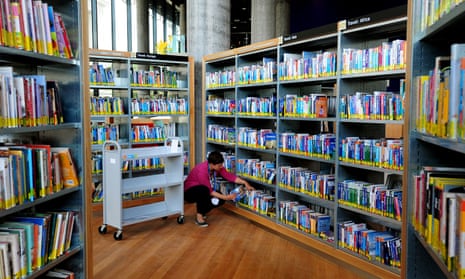

Until very recently, every local public library was part of a joined-up national network. In even the smallest library, people could be sure to find certain basics such as books and PCs, plus trained staff able to provide a gateway to national assets, including standard online reference works, national newspaper archives, a link to the British Library, access to the summer reading challenge for children in the summer holidays, and much, much more in terms of books, educational resources, reference material and contacts.

The whole point was to provide a standard service nationwide. But that has now gone. It is now pot luck whether your local library is a full service, or instead, some nice people with cast-off books donated by other nice people. Or something – almost anything – in between.

There’s no way to tell if this ramshackle provision can survive. It has been common for community-managed libraries to have problems finding enough volunteers, or funding. Most residents have been grateful to have any kind of community facility.

But volunteer libraries have already ceased to provide a full, national library service. The taskforce did not ask about the quality of service in community-run libraries, so there is little information about the range and depth of books being stocked, or what kind of IT facilities are being provided. The research team could not even use a basic measure: the number of books being issued.

The government has sat back and watched the most drastic change in decades to an essential frontline public service. In an affluent country, with key needs for information and human connection, this is unforgivable.

Talk to us on Twitter via @Gdnvoluntary and join our community for your free monthly Guardian Voluntary Sector newsletter, with analysis and opinion sent direct to you on the first Thursday of the month.

Looking for a role in the not-for-profit sector, or need to recruit staff? Take a look at Guardian Jobs.