Approach Considerations

Most individuals with cleft lip (CL), cleft palate (CP), or cleft lip and palate (CLP), as well as many individuals with other craniofacial anomalies, require the coordinated care of providers in many fields of medicine (including otolaryngology) and dentistry, along with that of providers in speech pathology, audiology, genetics, nursing, mental health, and social medicine.

Treatment of orofacial cleft anomalies requires years of specialized care and is costly. The average lifetime medical cost for treatment of one individual affected with CLP is in the area of $100,000. [3] Single-stage repairs have been associated with lower costs than staged repairs. [47] Although successful treatment of the cosmetic and functional aspects of orofacial cleft anomalies is now possible, it is still challenging, lengthy, costly, and dependent on the skills and experience of a medical team. This especially applies to surgical, dental, and speech therapies.

Because otitis media with effusion is very common among children with CP, involvement of an otolaryngologist in the multidisciplinary treatment plan is very important. The otolaryngologist performs placement of ventilation tubes in conjunction with the CP repair. [48] If a concurrent CL is present, the ventilation tubes are placed during that repair. Many of these children see otolaryngologists well beyond the time they see many of the other specialists because some children continue to have eustachian tube dysfunction after their palates are closed.

A team for the multidisciplinary treatment of a child with an orofacial cleft includes the following specialists:

-

Pediatrician

-

Nurse practitioner

-

Plastic surgeon

-

Pediatric dentist

-

Otolaryngologist

-

Geneticist

-

Genetic counselor

-

Speech pathologist

-

Orthodontist [49]

-

Maxillofacial surgeon

-

Social worker

-

Psychologist [5]

No single treatment concept has been identified, especially for CLP. The timing of the individual procedures varies in different centers and with different specialists.

The following is the most common treatment protocol currently used in most cleft treatment centers:

-

Newborn - Diagnostic examination, general counseling of parents, feeding instructions, palatal obturator (if necessary); genetic evaluation and specification of diagnosis; empiric risk of recurrence of cleft calculated; recommendation of a protocol for the prevention of a cleft recurrence in the family

-

Age 3 months - Repair of CL (and placement of ventilation tubes)

-

Age 6 months - Presurgical orthodontics, if necessary; first speech evaluation

-

Age 9 months - Speech therapy begins

-

Age 9-12 months - Repair of CP (placement of ventilation tubes if not done at the time of CL repair)

-

Age 1-7 years - Orthodontic treatment

-

Age 7-8 years - Alveolar bone graft

-

Older than 8 years - Orthodontic treatment continues

Other surgical procedures can be performed in patients with severe clefts as necessary (see Surgical Therapy).

Medical Therapy

Neonatal care

When a neonate with a cleft is born, a pediatrician has three major concerns:

-

Risk of aspiration because of communication between oral and nasal cavities

-

Airway obstruction (in addition to sequelae of aspiration, especially in Pierre Robin sequence, where the CP is combined with micrognathia and the tongue has a normal size)

-

Difficulties with feeding of a child with a cleft and nasal regurgitation

These three factors are influenced by the presence of other major or minor anomalies that may, in association with a cleft, represent one of 300 known cleft syndromes. [7] Therefore, a neonate with an orofacial cleft should be seen by a medical geneticist as soon as possible.

As with any other medical condition, each case is different. A child with a severe cleft may do very well, whereas a child with a much less severe condition may experience many problems. An individual approach is necessary; however, several major rules apply to every neonate born with a cleft.

A pediatrician or neonatologist is usually the first person to take care of a neonate born with a cleft and the first to talk to the parents. As soon as possible, each baby born with orofacial cleft should be referred to the cleft palate or craniofacial center, where each specialist evaluates the baby, delineates the best management options and treatment plan, and continuously revises individual procedures and treatment during follow-up visits.

Feeding of infant with cleft

The vast majority of children with cleft lip and palate anomalies are born with a normal birth weight. However, because of feeding and other difficulties mentioned above, the most common problem the pediatrician has to deal with is insufficient weight gain. One of the pediatrician's main responsibilities is to closely monitor the infant's weight. Pediatricians may supervise mothers themselves or may refer them to a nutritionist, feeding specialist, experienced nurse practitioner, or other specialist.

Most children born with CLP are unable to be breastfed. Those with CP cannot produce the negative pressure necessary for suction. Mothers of children with a unilateral CL may succeed with breastfeeding when the child is positioned so that the cleft in the lip is obstructed by the mother's breast.

No single right or correct method of feeding has been identified. Parents, working together with the healthcare provider, should choose the method that is best for their infant. Most infants can complete a feeding in 18-30 minutes. If more than 45 minutes is required, the infant may be working too hard and may be burning calories that should be used for weight gain. An infant who nurses or bottle feeds every 3-4 hours tends to gain weight better than an infant who feeds frequently (feedings < 2 hours apart) for short periods.

Helpful hints for a parent breastfeeding an infant with a cleft are as follows:

-

In a case of an isolated CL, the infant typically does not experience feeding problems beyond learning how to "latch on" to the nipple at the beginning of the feeding; infants with CP must squeeze the milk out of the nipple by compressing the nipple between the tongue and whatever portion of the palate that remains

-

Massaging the breast and applying hot packs on the breast 20 minutes before nursing usually helps

-

The mother should apply pressure to the areola with her fingers to help the engorged nipple protrude; she should hold the infant in a semiupright, straddle, or football position; she should support the breast by holding it between her thumb and middle finger, making sure that the infant's lower lip is turned out and the tongue is under the nipple

-

If the infant cannot hold onto the nipple any more, the mother can collect the remaining milk using an electrical or manual breast pump or by squeezing the breast with both hands and can finish the feeding with collected milk in a bottle

-

The mother should increase her fluid intake (eg, by drinking larger quantities of water)

Hints for feeding breast milk with a bottle are as follows:

-

Particularly for infants with bilateral CLP, breastfeeding is not possible

-

The mother can use a breast pump (an electric pump ensures the highest level of success); then, she can feed the baby with a bottle (see below)

Hints for feeding milk formula with a bottle are as follows:

-

The most appropriate milk formula should be selected by a pediatrician or feeding specialist

-

Various nipples and bottles are made specifically for infants with clefts; the goal is to find a nipple and bottle that make feeding easy for the infant and still allow ample opportunity to suck

-

A soft nipple is generally better than a hard nipple (some can be softened by boiling)

-

Use a crosscut nipple to prevent choking; any nipple can be crosscut manually by using a single-edged razor blade; the crosscut is on the tongue side

-

The bottle should be squeezed and released, not continually squeezed

-

The nipple is angled to a side of the mouth, away from the cleft

Other recommendations include the following:

-

More upright or seated positions prevent the milk from leaking to the nose and causing the infant to choke

-

Advise the mother to stop feeding and allow the infant to cough or sneeze for a few seconds when nasal regurgitation occurs; a palatal obturator may be used

Gaining weight and preventing aspiration and ear infections are the most important parts of caring for neonates with a cleft during their first days and weeks of life.

Surgical Therapy

Undoubtedly, closure of the CL is the first major procedure that tremendously changes children's future development and ability to thrive. Variations occur in timing of the first lip surgery; however, the most usual time occurs at approximately age 3 months.

Pediatricians used to strictly follow a rule of "three 10s" as a necessary requirement for identifying the child's status as suitable for surgery (ie, 10 lb [4.5 kg], 10 g/dL of hemoglobin, and age 10 weeks). Although pediatricians are presently much more flexible, and some surgeons may well justify a neonatal lip closure, [50] considering the rule of three 10s is still very useful.

Anatomic differences predispose children with CLP and those with isolated CP to ear infections. Therefore, ventilation tubes are placed to ventilate the middle ear and prevent hearing loss secondary to otitis media with effusion.

In multidisciplinary teams with significant participation of an otolaryngologist, the tubes are placed at the initial surgery and at the second surgery routinely. The hearing is tested after the first placement when ears are clear with tubes. If no cleft surgery is planned early, placing the tubes early [51] (eg, by age 6 months) and monitoring hearing with repeated testing is recommended.

Complications include eardrum perforation and otorrhea, particularly in patients with open secondary palates in which closure is planned for later.

For preventive reasons, ear tubes are usually placed when the child is still under general anesthesia for cleft repair.

Detailed surgical treatment is described elsewhere (see Craniofacial, Bilateral Cleft Lip Repair, Craniofacial, Bilateral Cleft Nasal Repair, Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Nasal Repair, Craniofacial, Unilateral Cleft Lip Repair). Pediatricians may find it useful to inform parents of the kinds of procedures that a child with cleft may undergo.

The most common surgical procedures for a child with a CLP anomaly are as follows:

-

Repair of the CL

-

Repair of the CP

-

Revision of the CL

-

Closure and bone grafting of the alveolar cleft

-

Closure of palatal fistulae

-

Palatal lengthening

-

Pharyngeal flap

-

Pharyngoplasty

-

Columellar lengthening

-

CL rhinoplasty and septoplasty

-

Lip scar revision

-

LeFort I maxillary osteotomy

Maxillary distraction osteogenesis is increasingly being used as an alternative to conventional orthognathic surgery for correction of maxillary hypoplasia in CLP patients. [52, 53]

Orthodontic treatment is highly specialized and varies from case to case. The two stages of orthodontic treatment of a child with CLP are as follows:

-

Surgery-related orthodontics - Early management (from birth until the time of surgical closure of the palate); orthodontics related to alveolar bone graft; permanent dentition management

-

Cleft-related orthodontics (not related to surgical treatments)

There has been considerable enthusiasm for employing presurgical infant orthopedics (PSIO) in CLP patients to improve surgical outcomes with minimal intervention. [54] Esenlik et al reviewed the literature on nasoalveolar molding (NAM) with an eye to both benefits and limitations. [55] Their review suggested that NAM does not alter skeletal facial growth but found evidence of benefits to patients, caregivers, surgeons, and society, including the following:

-

Documented reduction in the severity of the cleft deformity before surgery and, as a consequence, improved surgical outcomes

-

Reduced burden of care on caregivers

-

Reduction in the need for revision surgery

-

Consequent reduced overall cost of care to patient and society

There is growing interest in the application of robotics to cleft surgery. Initial studies showed this to be feasible; however, economic challenges remain, and optimal approaches are yet to be defined. [56]

Complications

Hypertrophic scarring is a frequent postoperative complication of surgical treatment of cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P), often necessitating multiple lip revision operations throughout childhood in an effort to improve aesthetics and function. [57] Dysregulated, exaggerated inflammation appears to contribute significantly to scar formation. Current therapies for hypertrophic scarring after CL/P surgery are not especially effective, but the use of specialized proresolving mediators of inflammation to accelerate wound healing may afford new therapeutic opportunities for managing this complication.

Approximately half of children who have undergone reconstructive surgery for CL/P have speech deviations by age 5 years. [58] Many such children may be helped by speech-language therapy.

Prevention

Research on the association between orofacial clefts and folic acid consumption strongly suggested that a certain proportion of these serious anomalies can be prevented by periconceptional supplementation of folic acid and multivitamins. The preventive approach is assumed to be especially successful in those situations where environmental factors represent a substantial part of the etiologic background.

Primary prevention (ie, prevention of a birth defect before it develops in the embryo or fetus) is attempted for prevention of recurrences in at-risk families to which a previous baby with the anomaly has been born; it is also applicable in the general population for prevention of occurrences.

Decades after initial experimental animal studies indicated that vitamin deficiency in a mother could cause congenital malformations in the offspring, [59, 60, 61] formiminoglutamic acid excretion testing for defective folate metabolism was found to be positive more often in women pregnant with a child with a neural tube defect (NTD) or another congenital abnormality than in control subjects. [62] Furthermore, periconceptional supplementation with multivitamins [63] or folic acid [64] was found to have a role in the prevention of NTDs.

Nonetheless, prevention of congenital anomalies seemed impossible to realize as the ultimate goal of teratology [65] until a randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial sponsored by the British Medical Research Council (MRC) showed a 72% decrease in the recurrence of NTDs when women ingested 4 mg/day of folic acid from the day of randomization before conception and for 12 weeks thereafter. [66, 67]

However, prophylactic multivitamin therapy, including folic acid, was first used to prevent CLP anomaly in future offspring of women whose first child had CL/P. [68, 69, 70]

On the basis of these study results, Burian (of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague) initiated a study in which women who had given birth to a child with an orofacial cleft began taking the multivitamin supplement preparation Spofavit (vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, C, D3, and E; nicotinamide; and calcium pathothenicum) either immediately after a subsequent pregnancy was confirmed or periconceptionally when pregnancy had been planned. [71]

Although Burian's observations were mainly empirical, a prospective trial of periconceptional multivitamin and high folic acid supplementation was conducted in women at risk for giving birth to a child with CL/P.

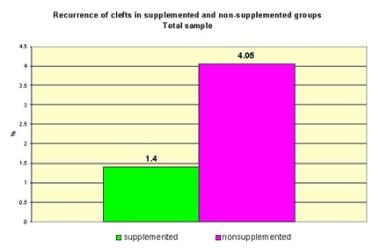

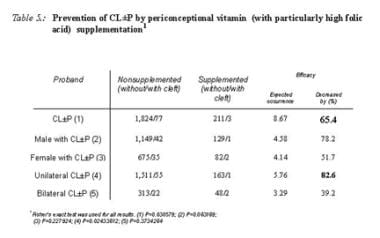

In a nonrandomized prospective interventional study from the Czech Republic, including 221 pregnancies in women at risk for a child with CL/P, a dramatic reduction of cleft recurrences was found after periconceptional supplementation with Spofavit and high-dose folic acid (10 mg/day). [72, 24] Supplementation began at least 2 months before planned conception and continued for at least 3 months thereafter. A comparison group, comprising 1901 women at risk for giving birth to a child with CL/P, received no supplementation and gave birth within the same period as the study group.

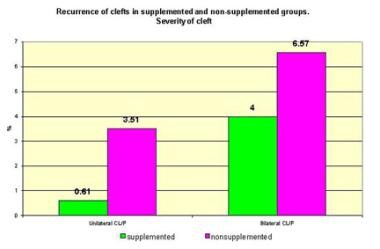

In the supplemented group, three of 214 informative pregnancies resulted in neonates with CL/P, a 65.4% decrease from the expected value (see the image below). [24, 72] Subset analysis by proband sex, severity of CL/P, and both variables showed the highest supplementation efficacy in probands with unilateral cleft (82.6% decrease from the expected value).

No efficacy was observed for female probands with bilateral CL/P. Generally, the efficacy was higher for subgroups with unilateral clefts than for those with bilateral clefts and for male than for female probands (see the image below).

Prevention of cleft lip and palate by periconceptional vitamin (with particularly high folic acid) supplementation.

Prevention of cleft lip and palate by periconceptional vitamin (with particularly high folic acid) supplementation.

Similarly, a large population-based case control study of fetuses and live-born infants in the 1987-1989 cohort of births in California reported that periconceptional use of multivitamins, which usually contain 0.4 mg or more of folic acid, reduced the occurrence of CL/P by approximately 27-50% (see the image below). [73] In this study, 734 mothers with an infant with an orofacial cleft and 734 control mothers with an infant without a birth defect were evaluated.

In contrast, the study completed by Hayes did not support a protective association between the periconceptional folic acid supplementation and the risk of oral cleft. [74]

However, the most interesting results supporting high-dose folic acid in the prevention of nonsyndromic clefts were those of Czeizel et al in the Hungarian Case-Control Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies. [75] This randomized double-blind, controlled trial of periconceptional supplementation with a multivitamin including a low "physiologic" dose of folic acid (0.8 mg/day) showed no preventive effect on the first occurrence of isolated CL/P or CP alone; however, the general evaluation of congenital anomalies indicated a reduction of nonsyndromic clefts after the use of high-dose folic acid (3-9 mg/day) in the early postconception period.

A subsequent article by Czeizel discussed these two controversial findings and suggested a "dose-dependent effect" of folic acid in the prevention of orofacial clefts. [76]

-

Classification of orofacial clefts.

-

Examples of cleft lip.

-

Examples of cleft lip and palate.

-

Examples of cleft palate.

-

Submucous cleft palate.

-

Bilateral cleft lip on ultrasound.

-

Median cleft lip on ultrasound.

-

Prevalence of orofacial clefts (Tolarova and Cervenka, 1998).

-

Recurrence risk in cleft lip with or without cleft palate.

-

Highest and lowest risk of recurrence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate.

-

Recurrence risk in cleft palate.

-

Etiology of cleft lip and palate anomalies.

-

Multifactorial threshold model for the distribution of liability for cleft lip and palate.

-

Four-threshold multifactorial threshold model of the liability for cleft lip and palate.

-

Recurrence of clefts in supplemented and nonsupplemented groups.

-

Prevention of cleft lip and palate by periconceptional vitamin (with particularly high folic acid) supplementation.

-

Recurrence of clefts in supplemented and nonsupplemented groups, severity of cleft.

-

Decreased occurrence of orofacial clefts.