Translation matters: The unsung heroes of world literature

26 February 2015

Is it possible to appreciate the pleasures of foreign books, without going to the trouble of learning another language? Step forward the mighty translators, the often unsung heroes of world literature. As Penguin celebrates its 80th year with the Little Black Classics series - including 48 translations of non-English texts, award-winning translator ANTHEA BELL writes for BBC Arts about the value of translation.

Edith Grossman’s short book Why Translation Matters tells readers why. Most translators love it, and her title was not framed as a question, but I have heard similar wording that asks: does translation matter? I’ve also heard that answered in the negative.

A couple of decades ago, at a PEN International Day on translation in London, I was on a panel that also included the late Michael Henry Heim. Just before our event, a famous pundit who shall be nameless swept in, and announced from the stage that all translation was by definition useless, pointless and downright bad.

A famous pundit announced from the stage that all translation was by definition useless

She then read aloud a good deal of poetry in Spanish with no concessions to anyone in the audience who didn’t know the language, and swept out again without giving any time for questions. It was left to our panel to pick up the pieces.

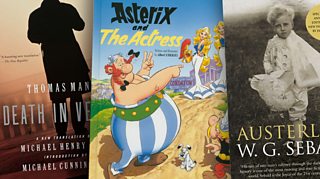

Some years later I met Michael Heim again in Chicago, where W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz had just won the Wolff Prize for translation from German; Michael himself won it three years later with his new version of Mann’s Death in Venice. He thought that Chicago was our first meeting, but when I reminded him of the earlier occasion he did recollect it. It had been such a grim moment, he said, that he must have unconsciously deleted the memory from his mind.

We did our best on that panel to retrieve the reputation of translation and translators – if translators were an evil, surely they were a necessary evil. Luckily everyone present had only to recollect the opening event of the day, a talk by Michael Ignatieff on literary translation, to see our point.

As Ignatieff said, it is incontrovertible that if we are to have international literature, we need translation. And for translation, you need translators. Few, after all, would go to the cheerful depths of ignorance reflected by the (surely apocryphal) story of the Texan who proclaimed that if English was good enough for Jesus Christ, it was good enough for him. Which is not to say that the King James version of the Bible, itself a translation based on the previous work of Wycliffe and Tyndale, isn’t one of the great glories of English literature, right up there beside its close contemporary Shakespeare.

Other questions arise. If translation is needed, who are the people who decide it is the profession for them, and why, and how do they get to be translators? With me it was accidental. I had studied the early history of the English language at university, because I like to know about the roots of things, but I had never stopped reading widely in German and French.

Do foreign authors really want their books translated into English? You bet they do

One language is not enough for bookworms. If you want to read books in the original, ironically enough you qualify yourself to be a translator. There are in fact no special qualifications. I feel upset when young people write to me saying they’ve never done a post-graduate course in translation theory; can they still become translators? Translation theory is probably fun in its way, but I have never met a publisher who cared in the least whether you knew anything about it.

I spoke once to students on a post-graduate translation degree course, and Melissa Ulfane, founder of Pushkin Press, speaking next, was surprised to be asked about translation as an act of violence. Wasn’t the translator raping the original? I’d heard this before, and however tenable the idea may be in theory it is deranged in practice. The students’ next question was: do foreign authors really want their books translated into English? You bet they do. Far more books are translated out of than into English. So there’s competition, and writers definitely want to get their work sold on the huge English-language market.

Then, what does translation entail? It’s a trick of the mind, very difficult to describe except by metaphor. I tried dispensing with metaphor once at a discussion event. You read the original, I said, you know what idea you want to express, and the mind pauses briefly in a place where neither language really exists, then comes down in the language of translation. Ah, said an Italian author present, and what exactly is this place? I’d simply coined yet another metaphor. Here’s one more: many of us think of translation as acting, but on paper – and whatever the pundit at the PEN day thought, like acting, it is an honest craft.

One last point. In the Little Black Classics series, out of eighty mini-books, more than half are translations. Leaving aside internal clues, I’d defy anyone to say which were and which were not originally written in English. I rest my case for translation.

The Little Black Classics series is released on 26 February 2015 to mark the 80th Anniversary of Penguin Books.

About the author

Anthea Bell's translation career began by accident when her publisher husband asked her to write an English version of a German children's story. She learned French and German at school, and later taught herself Danish.

In 1969 she translated her first Asterix book and is celebrated for her work on the series. In 2013 she translated her 35th adventure Asterix and the Picts.

In 2002 Bell received the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize and the Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize for the translation of W. G. Sebald's Austerlitz. She was honoured with an OBE in 2010 for services to literature. She lives and works in Cambridge.

Penguin at 80

-

![]()

Designing obsession

The iconic book designs and the artists who created them

-

![]()

Spine tingling

Brian Morton looks back at the colourful history of Penguin

-

![]()

Translation matters

Anthea Bell on the value of translation in world literature