It was September in Oregon the first time I ran a mile. Or “the mile,” I should say. I was 11 years old, just recently made aware of how wrong my body and clothes and hair and family were (chubby, cheap, cut by my father, weird).

I was not very good at it.

It took me 12 minutes and 20 excruciating seconds. I remember this fact because the next time we had physical education, everyone who’d run the mile in under 12 minutes did a short jog and then played a game. The rest of us puffed our way through four more humiliating laps. It still took me just over 12 minutes.

In all the talks about middle school—about having lockers and changing periods and learning to play the flute—no one had told me about this. I had no idea how to run properly: terrible form, no sense of pacing, no way to tell whether I was doing it right. Only the look of disappointment on Mrs. Burris’s face to let me know I was doing it wrong.

Mrs. Burris meant well. She wanted everyone to be healthy. She fed her own kids sugar-free pancake syrup and low-fat everything. She was fit, brisk, and seemingly always clad in a teal-and-purple jogging suit and a Nike visor. And she believed that with enough training, I could run the damn mile faster.

Instead, I dreaded it. I plodded along in my Payless sneakers as the fastest kids lapped me. I resented the happy-looking girls, their ponytails bouncing further and further into the distance. I didn’t understand how anyone could be anything but miserable.

Training our way to indifference

We web-makers spend lots of time training people, too. As a content strategist, I often find that means training authors—the editors or marketing managers or communications specialists or whoever it is inside an organization who’ll be responsible for producing content and managing it in a CMS.

Our web-team processes may be more collaborative and iterative than ever—we may be sketching, testing, adapting, and prototyping. But how often are the people who’ll live out our strategies and manage content for the long term—the people who, ultimately, hold the power to make or break our users’ experiences—included in that process?

Instead, we round them up at the end of a project, plunk them down in front of a new system, and deliver a training session. Here’s how the CMS works. Here’s the taxonomy to use. Here’s what goes in this field. It’s passive: information is delivered to them—the old empty-vessel education system reimagined in a corporate conference room. And then we wonder why they won’t follow directions, why they’re resistant to the new system, why they stopped tagging their content after a week, dammit.

Pick up the pace, Boettcher.

Only they have no idea how to go faster. They’re sucking air, hating our whistle and our sporty visor and our enthusiasm.

We’ve told them the steps, but the steps feel foreign and arbitrary—disconnected from the staff’s day-to-day roles and lives.

We’ve provided training. What they needed was practice.

Practice as pedagogy

Instead of training—figuring everything out and then telling people how to follow the rules—practice is about action. It’s a thing you do, not a thing you receive.

Practice is how we learned to do most of the things we’re good at: reading, writing, driving, cooking, dancing, painting, whatever. We might have received training in a specific aspect of any of these things—Here’s how you make a cursive Q—but none of us mastered them that way.

We mastered them by doing them, over and over, until we built muscle memory—until making letterforms or parking between the lines or whisking flour and butter into a roux stopped feeling like a list of steps and started feeling natural. Until it became part of us.

Training sessions and screenshots of CMS interfaces are a start, but they’ll never help a team of content creators and managers own the content process. That’s what practice is for.

This distinction has changed my work dramatically over the past couple of years—leading to content workshops using activities and approaches that begin earlier and extend beyond a web-writing or CMS training session.

Here’s what I’ve learned—and some activities you can steal, adapt, and experiment with, too.

Get a feel for things

It’s easy for me to tell someone all the things that are wrong with their content—this is a big blob, this is passive, this is difficult to understand. Whether I’m editing A List Apart or working with clients or writing essays like this, I spend my life immersed in content. Of course I’m good at noticing where a subhead’s needed or when an author slips into jargon.

Sometimes that’s useful—external perspective can help set the stage for change or get stakeholders on board. But ultimately, what I really need isn’t for me to notice these problems, but for the authors themselves to start seeing them—before I point them out.

It’s hard for people to assess their own content, though. It requires taking a step back and evaluating content as an outsider, as well as acknowledging weaknesses without beating yourself up.

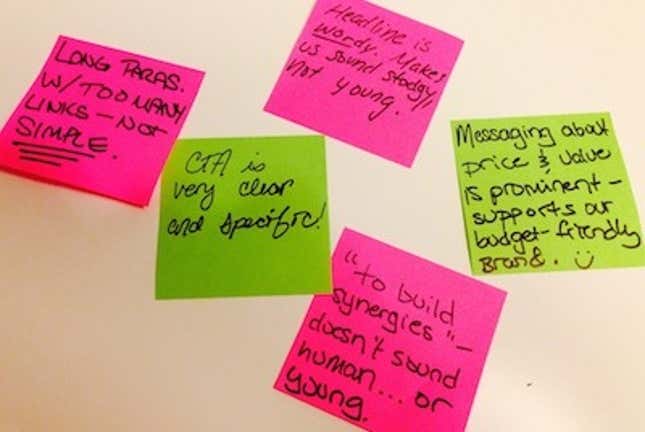

So I started using an exercise in my workshops to help people look at their content through new eyes, and to apply strategic principles to it. I call it a sticky note analysis, and it’s ideal to do once you’ve agreed on some kind of strategic foundation or direction for your content—whether those are a set of principles and priorities, a new brand and voice direction, or a mandate to adapt to mobile. It goes something like this:

- Revisit the strategic decisions you’ve made so far. Remind everyone of what they agreed they wanted their content to be like in the future, and how it’s supposed to help their users.

- Print out pages of existing content and tape them to the walls. If you’ll have people from different departments in the session, pick at least one example from each person’s area of expertise. (I’ll often print pages straight from the website, blown up onto legal-size paper.)

Have participants define what’s working—and not working—using two colors of sticky notes. I like red and green for stop and go (though hot pink works, too). - Hand each participant a marker and two colors of sticky notes—if possible, red and green—and have the room look at each example. When they see something that aligns with what you’ve all agreed on, have them write it on a green sticky note and post it next to that spot. When they see something that doesn’t fit the goals, have them write it on a red sticky.

- Once everyone has had a change to comment on every page, discuss what they found: What trends did they see? What was difficult about this activity? What surprised them when they started digging into the content?

Doing this sets the stage for writing and editing, because it gets participants’ brains thinking differently about the content they create. When everyone has practice applying their strategies and principles to real content, you’re more likely to get a strategy that’s lived, not just dumped into a PDF and left to rot on some server.

Keep the stakes low

It’s hard enough to change your habits. It’s even harder when you feel exposed during the process—like everyone will suddenly know that you don’t get it, that you’re not good enough at this web stuff. That following the new guidelines is hard for you.

The truth is, change is hard for everyone. And the web? It’s nothing but change.

We can’t make writing chunks instead of blobs—or tagging content according to themes and categories—or to talking to users instead of about your company—painless for people. But we can help lower the stakes by giving them a space to practice that feels safe.

I like to do this with pair writing. Working with a partner gives participants the sense that they’re not in it alone—that they have someone to bounce ideas off of, and also that they’re not the only person to find this task challenging. Participants are more likely to admit their gaps in knowledge, because they had them together—rather than assuming everyone else got it and they were the only one who struggled.

Pair writing and editing also helps participants examine their communication choices more thoroughly—because they have to explain and discuss and defend their decisions about what to emphasize, what to cut, and how to phrase things to another person. When they do, they get better at being purposeful in their writing—and at making sure others understand it.

I like to make pair writing the next step to the sticky-note activity I talked about earlier, but you can also run this as its own activity. Here’s how I do it:

- Pair people one of two ways: either match people who work on the same kinds of content (good for when you need a high degree of subject-matter expertise, or you feel like team collaboration is flagging), or match people who do very different things and don’t usually work together (good for when content silos have caused some of the problems you’re trying to solve with your project).

- Assign each pair a page of content relevant to their actual work. Ask them to collect the copy from the wall, as well as all those red and green sticky notes.

- Have each pair discuss their content: What trends did they notice in the feedback? What should they prioritize? Where should the content start? What could be cut?

- Give them a limited amount of time to rewrite their content—say, 30 minutes. Tell them it’s okay not to finish, and it’s okay for things to be rough. The point is to start.

- Once time’s up, have each pair share with the larger group and get feedback.

Pair-editing makes it possible to draft, get feedback, edit, and iterate in a fluid, natural way. It teaches everyone to be both more purposeful in their writing, and more comfortable asking their colleagues for input. Most of all, it helps people simply get started—helps them get over the hurdle of beginning a big content project, rather than sending them back to their desks with nothing but a massive assignment and a distant deadline.

Facilitate, facilitate, facilitate

Helping people practice takes a shift in mindset, though—from expert to listener, from strategist to facilitator. While I do spend some time showing people how to do things, I invest the most time in helping them see things for themselves.

I do this by using my expertise to provide guidance and support, not just the answers. In my work, this means asking questions that progressively push people beyond their comfort zones—questions like:

- Which of our content principles were thinking about as you wrote this?

- How did you select those categories for this piece of content?

- Why are those details important to include in this 25-word teaser?

- What are you hoping a user remembers from this page?

Questions like these are all about encouraging people to put purpose in their content—to think about and be able to articulate why they’re doing what they’re doing at every moment.

I’ll also ask the rest of the group questions to get them used to assessing their peers’ content in a productive, constructive way. These might be things like:

- What’s something that works really well about this content?

- Is there anything you didn’t understand?

- We talked about using plainer language (or whatever the goal is) wherever possible. Are there any words you’d suggest simplifying?

- Is there anything here that doesn’t feel helpful (or whatever attribute you’re trying to foster)? What? Why?

This line of questioning usually starts broad, then gets more specific to help lead the conversation forward. Oftentimes it helps to find a detail in a participant’s explanation or feedback, and tease it out: What do you mean by that? Why does that matter?

This doesn’t mean all you do is ask questions. You can still provide recommendations; you just don’t start with them. Instead of leading with your expert opinion, you get people thinking first, and then give your own input bit by bit to help them along.

Start early, repeat often

I’ve picked out a couple ideal moments for practice here, but there are a million more—and they’re worth working into your process at every step along the way. It takes time for a new skill or a change in behavior to feel natural.

You might start including a content analysis activity in your kickoff meetings, rather than just a discussion. Or you might want to bring authors into the design process and have them help decide what goes into a wireframe or prototype.

Ultimately, practice is just that: a repeated activity that, over time, makes people feel proficient, prepared, and comfortable with their roles. It can’t be crunched into a two-hour training session three weeks before launch.

Success is what’s sustainable

I didn’t learn to run properly for years—not until a friend convinced me to sign up for the cross-country team our junior year—visions of getting thin (nope) and more attractive to my peers (double nope) sitting somewhere in the back of my brain.

I still wasn’t any good. But I did the drills—the hill sprints, the high knees, the long runs past the old airport and around the orchard. Slowly, my form improved. I recognized the way my right foot pronated and learned to correct it. I stopped starting too fast. My times dropped a bit.

I was the slowest person on the team.

But 15 years later, I’m still running—and I’m faster now than I was back then. Even when I don’t want to or it feels hard or I’m jetlagged or I’d really rather just curl up and binge-watch Scandal, I can lace up and jog a few miles. I’m comfortable with the rhythm of feet against pavement, feet against dirt, feet against track or gravel or sand.

Over the years, all that practice became a part of me. It made something hard and alienating feel more comfortable. Routine. Achievable. Practice made it easier to drown out the little voice in the back of my head that said, “do you really have to do all this?” and just get out there and do it.

It’s still hard. The difference is that I appreciate its difficulty. I know how to push through it. And I know how satisfied I’ll feel once I do.

And that’s what we need in web work. We need user centricity, purposefulness, and thoughtfulness to make their way into our authors’ content whether we’re around to blow the whistle on them or not. We need people to feel like they’re doing things right, and that all their hard work will be worth it in the end.

Practice doesn’t actually make perfect. You’ll still find formatting flubs and imperfect editing and a million little flaws in your colleagues’ or clients’ content. But it does something far more important: it makes people prepared—not just for the content and CMS they have now, but to ask questions, analyze, and rethink things—skill that will help them, whatever they need to adapt to next.

This post originally appeared at SaraWB.com. Follow Sara on Twitter at @sara_ann_marie.