Cotton makes up a third of fibre consumption in the textile industry, according to a global apparel fibre consumption report (pdf) published in 2013. The cotton production industry is labour intensive and involves a lot of sweat, chemicals and fresh water.

Could a number of innovations from natural sources and raw materials compete with the unsustainable product of the cotton plant?

Banana stems

Around a billion tonnes of banana plant stems are wasted each year, despite research indicating that it would only take 37kg of stems to produce a kilogram of fibre. In 2012, the Philippine Textile Research Institute concluded that banana plantations in the Philippines alone can generate over 300,000 tonnes of fibre.

Eco-textile company Offset Warehouse recognises the banana’s potential and currently partners with an NGO in Nepal to ensure banana fabric production supports the artisan sector by relying on local skills, and that workers are paid fairly and operate in safe conditions.

The fabric is claimed to be nearly carbon neutral and its soft texture has been likened to hemp and bamboo. Offset Warehouse’s founder Charlie Ross says the material is perfect for jackets, skirts and trousers.

Pineapple leaves

Frustrated by the heavy use of chemicals in the leather tanning process, Carmen Hijosa, founder of Ananas Anam, developed Piñatex as an alternative to it and petroleum-based textiles.

“The greatest thing about Piñatex is probably that it’s made of leaf fibres … a byproduct of the pineapple harvest,” says Jaume Granja, a member of the Ananas Anam team, referring to the fact leaves are usually left to rot in the ground. “Our leaves do not need any additional land, water or fertilisers to grow.”

Making the material also brings benefits to the farming communities. The industrial process used to create Piñatex produces biomass, which can be converted into a fertiliser that farmers can spread into their soil to grow the next pineapple harvest. The material, which has similar appearance to canvas, is also biodegradable; Hijosa and her colleagues are working on a way to ensure that the coating is sustainable and toxic-free.

It’s likely to be some time before the material (note: Piñatex is different from piña, where fibres are combined with silk or polyester) will be found in shops, but initial prototypes show that, just like leather, it can be used to manufacture goods including shoes and handbags. The wait might be worth it – at £18 per metre, it would be roughly 40% cheaper than good quality leather, which can be priced at around £30.

Coconut husks

The humble coconut palm is often referred to as the ‘tree of life’, but its value goes beyond its meat, milk and water. The fruit’s husks have fibrous qualities. A thousand coconuts can produce 10kg of fibre, and there’s usually a harvest every 30-45 days.

Outdoor clothing companies Tog 24 and North Face are two brands adopting cocona – a textile operating under the name 37.5 Technology that is produced from a combination of coconut shells and volcanic materials – and becoming less reliant on synthetic materials as a result. For instance, Tog 24 jacket, Siren, is 55% polyester and 45% cocona. A spokesperson for 37.5 Technology says that the material is a particularly good choice for sportswear as it’s designed to improve performance.

Fibres from husks can also be turned into biowaste-based charcoal to be used by farmers as an organic fertiliser, as has previously happened in the Maldives. This could help improve soil quality, reduce pesticides and ensure that any coconut inspired fashion supply chain is circular.

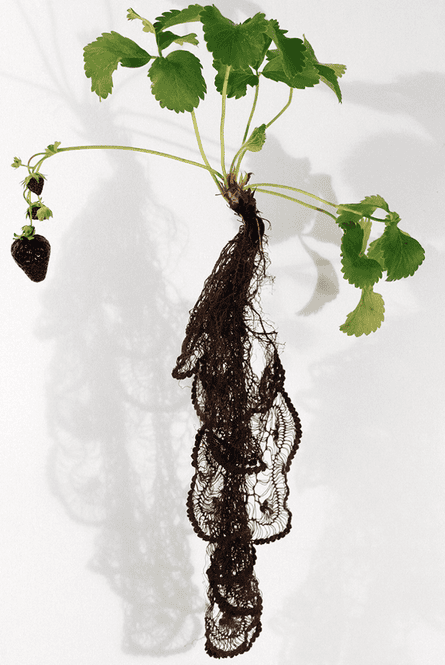

And one for a dystopian future – genetically modified strawberry plants

Designer and researcher Carole Collet, who set up the MA Textile Futures course at Central Saint Martins, has taken a Wonkalian approach to the concept of biomimicry, where nature and technology work in harmony to provide ecologically beneficial solutions. Her Biolace project imagines a future where plants are mini factories responsible for both food and textile production.

The project focuses on the possibilities of developing systems where plants can be genetically modified. For instance, a strawberry plant could eventually grow lace from its roots, as well as fruit. The lace could then be used to weave a dress.

A system where clothes could be manufactured using only the water and sunlight a plant needs to grow, and generating zero waste, would have big environmental benefits. Are we set to see a world where everyone has an engineered plant on a windowsill at home ready to meet our needs?

Growing our own textiles may be a nice antidote to fast fashion, but those slightly disturbed by the thought of it can rest easy. “They are speculative propositions of what we could do with biotechnology, should we choose to,” explains Collet. “But we are at least 20 years away from being able to do so.”

The sustainable fashion hub is funded by H&M. All content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled ‘brought to you by’. Find out more here.

Join the community of sustainability professionals and experts. Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion