In this new series, The Globe and Mail partners with award-winning platform Wondereur to explore the diversity of contemporary art from a completely new perspective. The Globe and Wondereur will approach radically different minds engaged in culture across the country and around the world. Each month, we will ask them to share with us the work of a contemporary Canadian artist who deeply touches them. To launch the series, we visit novelist Joseph Boyden at home in New Orleans for a discussion of how his taste has evolved, and to learn which artist he has chosen to highlight.

Was there art in your home while you grew up?

Iwouldn’t say my dad was a collector, but we were certainly surrounded by really interesting objects. My father had a fascinating story. He fought through the liberation of Italy during the Second World War, from Sicily all the way up. He was a frontline combat physician, and was wounded really badly at Monte Cassino. As he and his troops departed Italy on their way to the liberation of Holland, he bought a number of paintings he was told were from the 17th and 18th century. Lots of soldiers came back with these kinds of things. Souvenirs? Bounty of war? I’m quite sure ours were mostly reproductions of masters like Raphael, but they’re really, really beautiful – those daunting medieval characters or cherubic Renaissance faces staring at you from the walls. I remember staring back at them as a kid. Their eyes would follow me around the room.

When my mom sold our house in Toronto and all of us went our separate ways, we got to choose different pieces of art. I kept Joseph of Arimathea because this one hung above the stairway going from our main floor up to everyone’s bedrooms. Every night we’d look at him cradling the baby Jesus, this look of mild aggravation on his face, this look of “Christ, what a burden.” He actually brings back really good memories. Now the painting hangs in the bedroom I share with my wife, Amanda. He still looks slightly pissed that he has to deal with this little baby. For some reason, it’s a very comforting thing for me.

As you grew older, you were somewhat rebellious. Do you remember when you realized that art was more than just Renaissance reproductions?

It was the covers of punk-rock albums. Some are just horrendous but others were brilliant: you know, Minor Threat, Discharge, Husker Dü, Dayglo Abortions. I started getting more into punk rock from 16 on. The covers meant to shock, but not always. When the noise of hardcore grew too loud, I’d pick up a Joy Division album or the Velvet Underground and just stare at the cover as I listened. My eyes were really opened to the notion, “Wait, there is something – this new art – that isn’t just old and musty and dead and.…” The music was alive, the idea that music conjures wildly divergent images in your head, feelings in your body, was so alive. For a teenaged kid struggling to understand a confusing world, this was earth-shaking stuff.

And the Toronto scene was current: The scene, the music, the art, it all speaks to the moment, speaks to a very specific time, speaks to the culture of the suburbs we all desperately wanted to rebel against. Anyone in Toronto in the early eighties and into the punk-rock scene knows exactly what I mean. I loved the album covers with a double entendre rather than the ones trying to drive home a singular point too hard. I loved the album covers stuff you could see from many different angles at the same time. That fascinated me because that’s what writing’s like, too. There’s that kind of writing that just simply says what it says, and then there’s that writing that sometimes does the Hemingway analogy of the iceberg: We only see that one part of it above the surface, but we sense the real weight, the other 9/10s hanging just below.

Did you go to museums and galleries when you were young?

I really liked museums a lot, the chance to see different cultures, what their idea of aesthetic beauty is. What Torontonian my age didn’t go to the ROM to see King Tut as a kid when he rolled into town? Now that was exciting. That was brilliant marketing.

In my later teen years I was a roadie for the South Carolina punk band Bazooka Joe, and we all had this idea that as punks we need to do more than just be going to shows and slam dancing and drinking cheap beer. That we should ground ourselves in what the world offers us, that we had this responsibility to educate ourselves.

And so we’d do things like go to galleries and museums when we were on the road. Of course we’d try and sneak in or find a way not to pay. We were punk rockers after all. Art should be free! Art is not for the bourgeoisie! We’d ride into Santa Fe, for example, or New Orleans or San Francisco and we’d go to the coffee shop or independent record store and find out what’s cool around town then go and sniff around these different places. I was introduced to this crowd of people, wherever we went, who were not just into drinking and getting high and going to the show, but actually wanting to be artists.

And then you moved to New Orleans. How did it differ from what you’d seen before?

New Orleans, as you can imagine, lives close to the bone. There’s a lot of poverty in this city, and oftentimes, places that are impoverished produce great art. Beautiful work often comes from those most hard-knocked, it comes out of want, out of desire: street art and music and dance. Most of the cutting-edge stuff I can think of comes from those most hungry.

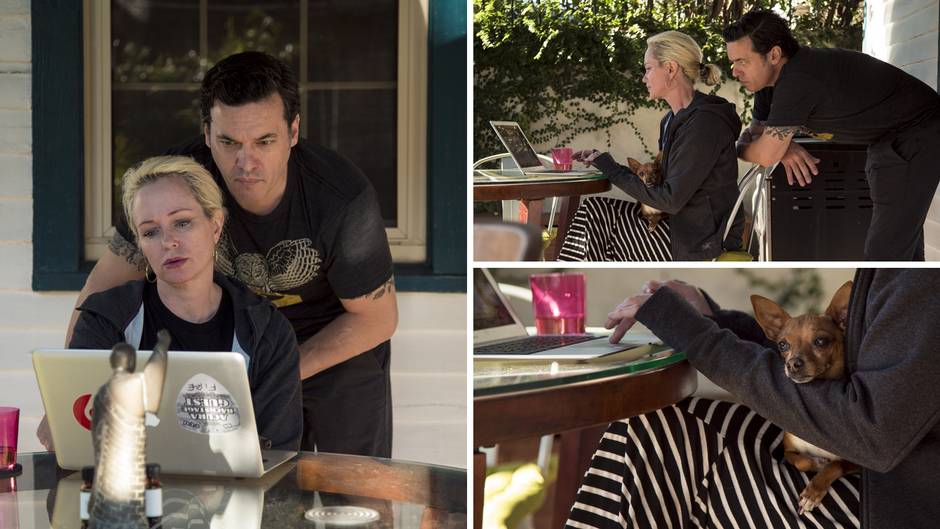

I think what I learned in New Orleans is that art can be very grounded in culture and place, to a degree that blew me away. The Mardi Gras Indians are a wonderful example of walking, living, breathing art. There’s a lot of cheese in New Orleans too, a lot of garish Bourbon Street garbage as well. I’m by no means a snob when it comes to art, but we all have our very strong sense of what we like and what we don’t, so we’re always looking for something that’s really individual and really specific to us. Quite a bit of the art that Amanda and I have in our house was purchased at the Jazz and Heritage Festival in New Orleans. There are these booths of artists, and again, it runs the gamut from absolute cheese to bizarreness to beautiful. We’ve bought a number of amazing pieces over the years. We love to collect the objects that grab us, that make us go, “Oh!” Even when we were poor, we were willing to spend all the money we had on art.

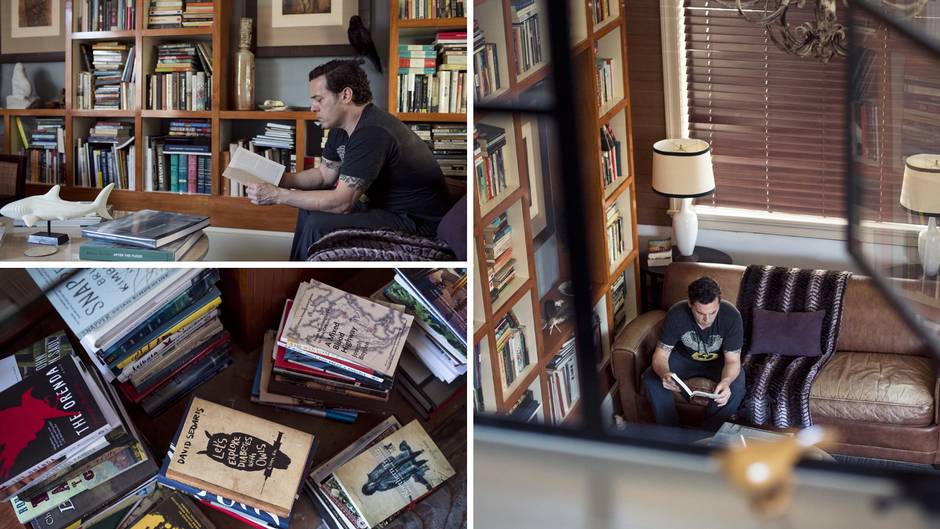

Inside Joseph and Amanda Boyden’s collection

Photos by Bryan Tarnowski

What did Amanda teach you about art?

To be more discerning. As much as I had spent years in this punk bohemian world, I was still undeveloped. I think that when I felt over my head, I was afraid to criticize, I was afraid to question. I’d too often accept. Which is a wonderful irony now that I look back on those punk years.

But when I say Amanda taught me to be discerning, I mean it in the best way. I don’t mean she taught me to criticize or to be a snob. I mean she taught me the importance of being able to look at something and actually be able to say, “This is what this means to me,” or “I don’t like this.This doesn’t speak to me because.…” And she taught me to be a little more careful. Just because a particular piece or song or dance was … just because it was one-of-a-kind or specific to something I knew or liked, didn’t mean I had to accept that as being art.

It’s interesting when your taste develops alongside another person’s like that.

My mom came down last Christmas with my youngest brother and his family. She walked around our house and says, “It’s just amazing, the combination of the two of your tastes, the two of your aesthetics, in a way that you wouldn’t think works but does.”

I’ve got an old plaster Indian. I don’t know if you’ve seen one, these were given away in carnivals in the 1920s and 30s. If you won a game, instead of getting a teddy bear you’d get a plaster Indian, about three feet tall. Ours holds sweetgrass and gifts that people have given to me. It’s beside one of my brother-in-law’s huge, vibrant pieces, and the two just speak to each other. Amanda and I are pretty selective – I think most people are when it comes to art and decorating their home, their living space, but we’ve got a very specific style. People always come over and I love it because they always say, “Ummm, do you mind if we wander around and take a look?” They don’t come over and say, “This house is crazy!” At least not to our faces.

Amanda and I spend more money than we should on art but the way we think of it, our home is our office, it’s our living space, it’s our ground zero, it’s where we spend the most hours of our day, so why not surround yourself with that which allows you to create? I love being surrounded by beautiful things when I’m writing. And it’s kind of sweet to support other artists.

So art helps you write?

I think so. And that might sound kind of cheesy. But I get a sense of comfort when I’m sitting at my kitchen table and look to my Indian at my left, some really cool photos by a photographer friend of ours to my right. Straight ahead I can look at the Parisian lamp fixture that we chose and it all just kind of gives a grounding sense: This is pretty. This is our space. This is my world.

In recent years, you’ve become more involved with native art and artists. How has your involvement in that community developed?

I sense a sea change happening in our country when it comes to aboriginal rights, aboriginal recognition, indigenous reclamation. Whether it’s aboriginal politics or art or music, there’s something big, something undeniable, happening in our country. And keep in mind that the fastest-growing population in our country is First Nations youth. And they’re hungry, and they’re talented, and so many of them live close to the bone, too. At the same time, the population four times more likely than any other population in our country to meet a violent end is aboriginal women, and the highest suicide rates in the world are among our own aboriginal youth.

But despite all of the injustice and tragedy, there are so, so many amazing stories blossoming out of indigenous Canada every day. Look at our artists and thinkers and musicians and writers: A Tribe Called Red, Taiaiake Alfred, Kinnie Starr, Hayden King, Tanya Tagaq, Richard Wagamese, Terril Calder, Nadya Kwandibens, Digging Roots. The list goes on and on! I want to believe that these voices far outnumber the tragedies, that they try to speak for those who can’t.

Some of the great art in the world is in response to politics and some of the greatest art in the world leads the way. When I hear the Prime Minister of our country say that our missing and murdered indigenous women are not really on his radar, it’s time for the artists to make sure these horrific crimes don’t continue to mount. And that’s when Kwe was born [a fundraising anthology Boyden edited last year]. It would’ve been much easier for me not to edit that book and just focus on writing my novels and not pester some of Canada’s greatest writers to give me their work for free. We could all just stay home and be quiet and be good little poets and do our jobs. But you know, it’s kind of fun, it’s exciting to be able to say, “Let’s get a gang of us together, let’s put out the call in one week and see how many writers will come.” It’s really exhilarating to know that, yeah, we have a voice. I’m not expecting a book like Kwe to change the discourse, but certainly it’s a step in the right direction. We the people, we the artists, still have a voice.

For this series, you’ve chosen to highlight First Nations artist Nadia Myre, who’ll be featured on the site of our partners on this project, Wondereur. Do you know her? Why do you like her work?

I don’t know her personally at all. I’ve never met her; I sure hope to. I totally admire Nadia, and I love her work. I think it’s eye-opening and it flips traditional native art on its head and makes a political statement, makes a social statement, all while being aesthetically gorgeous. She tears apart the stereotypes and clichés that people associate with native art then stitches them back together in a spellbinding way. I think that Nadia – like artists such as Maria Hupfield and Duane Linklater and Kent Monkmanand so many others – she’s changing the discourse. She’s reclaiming the discourse. The discussion for a long time has been what has been taken away from the First Nations of our country these last couple of centuries. As it should be. But the conversation I hear bubbling up, this talk of what’s been found, what’s never been lost, this most excites me. When you create something and put it into the world, it’s about giving up the ownership of it while at the same time understanding that in this loss, you just might change perception, even help guide the conversation. And I think that this is what Nadia Myre is doing.