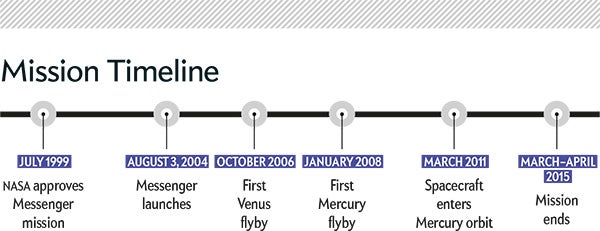

The first mission to orbit Mercury is nearing its end. Since arriving at the innermost planet in March 2011, the Messenger spacecraft has “rewritten the entire textbook on Mercury and the implications for the formation and evolution of the inner solar system,” says its principal investigator Sean Solomon of Columbia University. The probe was due to run out of fuel at the end of March, which would have initiated its gradual fall to the planet's surface. Recently, however, engineers found a way to squeeze a few more weeks' worth of propellant from its stores of helium, potentially pushing Messenger's demise into mid-April. The reprieve should allow sufficient extended time for measurements of Mercury's surface from within 15 kilometers—closer than ever before. Although the official mission will be over soon, astronomers now have more than 10 terabytes of data to keep them busy unspooling the mysteries of Mercury for years to come.

By the Numbers

8.6

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Mercury days Messenger has orbited the planet

1,504

Earth days Messenger has orbited the planet

4,105

Orbits of Mercury completed

258,095

Photographs returned to Earth

8.7 Billion

Total miles traveled

What We've Learned about Mercury

Weird Magnetic Field

In the 1970s Mariner 10's flyby revealed that Mercury has a magnetic field. Yet Messenger's observations showed that, strangely, the field is not centered inside the planet but instead is offset toward its north pole. Theorists have yet to explain what causes the asymmetry.

Volcanism

Messenger settled a long-running debate about whether volcanism is prevalent on Mercury. Previous imagery showed plains that could have resulted either from volcanic activity or from asteroid collisions. New data from Messenger indicated that these areas best match expectations for dried lava flows and that, in fact, volcanic material covers most of the planet's surface.

Surprising Formation History

Before Messenger, researchers thought Mercury had experienced periods of superhigh temperatures—up to 10,000 kelvins—during its early history, perhaps caused by an asteroid impact. Messenger detected surface metals that would have vaporized at such high temperatures, contradicting this theory.

Mysterious “Hollows”

Messenger revealed enigmatic flat and shallow bright spots littering Mercury's surface. Scientists dubbed them “hollows,” which appear to be unique to the planet. Experts' best guess is that these features form when volatile material from the surface is lost to space, perhaps through interactions with the solar wind of particles blown off the sun.