It is one of the ironies of impressionism, the quintessential French movement, that it had its beginning and its end not in Paris but in London. It is another irony that the key figure in the movement was not a painter but, that most maligned of species, a dealer. In 1871, having fled the Franco-Prussian war, Claude Monet was living in London. It was in January that year that the landscapist Charles-François Daubigny took him along to the inaptly named German Gallery on New Bond Street and introduced him to the proprietor, another French expat, named Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922). Whether or not the gallerist believed Daubigny’s words of introduction – “This artist will surpass us all” – he liked Monet’s work well enough to buy numerous canvases and, a few days later, paintings by his fellow artist-refugee Camille Pissarro, too.

This meeting and the chain of introductions, friendships and innumerable business transactions it put in motion was to culminate 24 years later with an exhibition just down the road on Bond Street at the Grafton Galleries. The exhibition, sometimes known as The Apotheosis of Impressionism, contained 315 pictures and was, and remains, the largest show of impressionist works ever held. For Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley and their peers it was final confirmation that their struggle to win acceptance for their unacademic, light-infused paintings had been successful. For Durand-Ruel, it was validation of his steadfast support for this group of avant-garde painters which had several times put him on the point of financial ruin. As he noted: “My madness had been wisdom. To think that, had I passed away at 60, I would have died debt-ridden and bankrupt, surrounded by a wealth of underrated treasures.”

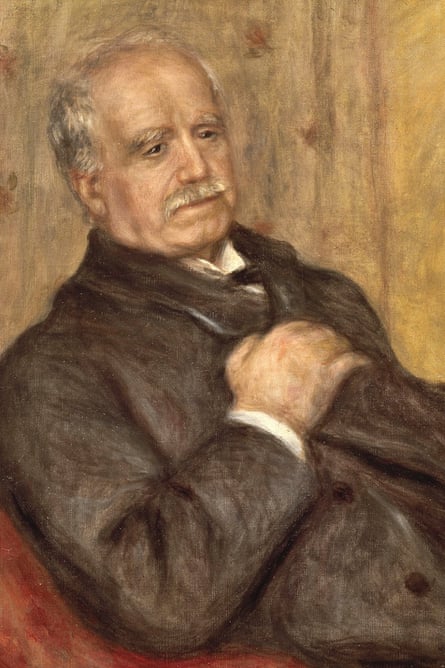

Innovative artists needed an innovative dealer and Durand-Ruel’s particular genius was not just to spot the talent of the young impressionists, but to promote them indefatigably and create a market for them where previously there had been none. It was a long-term project born of his faith that financial rewards – for the artists as much as himself – would come when the rest of the world saw them the way he did. To gain them the recognition he was convinced they deserved, he developed a range of new ways of promoting them that redefined the relationship between dealers and artists. Durand-Ruel’s achievement as cheerleader, entrepreneur, patron, and helpmeet is the subject of the National Gallery’s new exhibition Inventing Impressionism: The Man who Sold a Thousand Monets. Through 85 paintings, all but one of which passed through Durand-Ruel’s hands, it tells the story of the triumph of impressionism.

The match between the dealer and his painters was not seemingly a natural one. Durand-Ruel was a monarchist Catholic patriot, a stance born in part out of the experiences of his grandfather who had been imprisoned by Robespierre during the French Revolution and almost lost his head. “In a democracy,” Paul said, “everything goes awry and the blind claim to be steering the boat. The result is clear to see.” The would-be impressionists on the other hand were a heterogenous mix of republican liberals who, in Pissarro, also had one fully fledged anarchist (at one point he was on a police watchlist and his correspondence was regularly intercepted). Durand-Ruel was a conservative who nurtured radicals.

Nor was he an instinctive dealer. When he took over the business from his father, he initially went about his work with more of a sense of duty than enthusiasm. It was the 1855 Exposition Universelle, and in particular the 35 pictures by Eugène Delacroix on display there, that converted him. The paintings represented for him “the triumph of modern art over academic art ... they permanently opened my eyes and reinforced the idea that I might, perhaps, in my own humble way, be of some service to true artists by helping to make them better understood and appreciated”.

The artists to whom Durand-Ruel first rendered a service belonged to “the beautiful School of 1830” comprising Courbet and Delacroix and the Barbizon painters Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet. When he returned from London, Monet and Pissarro introduced him to Renoir, Sisley, Degas and the other leading players of their group and he took them up, too.

His care took various forms. He started to buy their work in bulk and paid them a monthly sum as well, dealing with their bills for everything from rent and tailors to paint suppliers and doctors. He doled out moral support, even offering Monet a room in his house to use as a studio. He did everything in his power to ensure that the artists, not yet the impressionists but the “intransigents”, were free to paint. “My fellow dealers,” he noted, “thought I was spoiling the artists.”

One example of his methods came in 1871 when he saw two paintings by Manet in the studio of the Belgian artist Alfred Stevens and bought them on the spot. Manet at this point was a hero figure to the proto-impressionists and a painter of some repute and notoriety who had, however, sold very few paintings. Durand-Ruel admitted that he had “never seriously looked at Manet’s work” and that he was “unaware of this artist’s talent”. The next day though he proceeded to Manet’s own studio and “bought on the spot, everything I found there”. This amounted to a cache of 23 paintings for which he paid 35,000 francs, a sum that freed the artist from all immediate financial concerns. Among the paintings were key works including The Dead Toreador and The Fife Player.

It took Durand-Ruel a year to pay off Manet, an indication of both the dealer’s limited funds and the extent to which he was willing to back his hunch that the artist would, at some point, come good in market terms. The bulk purchase is neatly recorded in a stock book held in the Durand-Ruel archives; a barely believable column of Manet after Manet, nestling among other purchases from Monet, Degas et al. Durand-Ruel’s own enthusiasm was not, however, widely shared; he recorded in his memoirs that the paintings “were not only misunderstood but they appalled most of my clients” and he sold them eventually for just a “few hundred francs profit”.

It was a problem Durand-Ruel faced repeatedly: “All my efforts were thwarted by the violent campaign mounted against Manet, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas and Puvis de Chavannes, and other artists whose works I had the audacity to show in my galleries.” He found himself and his charges “attacked and reviled by upholders of the academy and old doctrines, by the most established art critics, by the entire press and by most of my colleagues”. He had successfully set about creating a near monopoly in their works but he had cornered the market in paintings very few people wanted.

The situation was slow to change. As a result of repeated rejections by the official Salon, Monet, Degas and their colleagues had resolved never to exhibit there. Instead, in 1874, they held what became known as the First Impressionist Exhibition (they didn’t take on the group title until the third exhibition in 1877 when they adopted the critic Louis Leroy’s term of abuse as a badge of honour: the group had been dubbed impressionists since he derided Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise – “Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape”).

There were eight impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886 and Leroy’s reaction was typical of the reception that greeted them. Both public and critics were mystified by what they saw, baffled by the paintings’ lack of finish, their bright colours and quotidian subject matter (none of which stopped them coming to look anyway). Reviewing the 1876 exhibition at the Galerie Durand-Ruel, Albert Wolff of Figaro summed up the general feeling: “Following upon the burning of the Opera-House, a new disaster has fallen upon the quarter. There has just been opened at Mr Durand-Ruel’s an exhibition of what is said to be painting … Five or six lunatics, of whom one is a woman [Berthe Morisot], have chosen to exhibit their works. There are people who burst into laughter in front of these objects. Personally I am saddened by them.”

Faced by this public scorn Durand-Ruel had to find ways of changing public perception, without which his periods of financial crisis would become terminal. One of the ways to do this was by printing engravings after his stock. In 1873, for example, he produced a Recueil des Estampes Gravées à l’Eau-forte that included works he was selling by Goya, David, Delacroix and Courbet, as well as Manet, Monet and Pissarro. He mixed his moderns with earlier greats to suggest an unbroken artistic lineage.

Because the Salon and the Musée de Luxembourg permitted artists to show only one or two works at their exhibitions, Durand-Ruel took a novel approach and systematically started to hold solo exhibitions of his painters. Even though the painters were still young, these took the form of retrospectives and included early works as well as still-wet pictures straight from the studio. Some of Monet’s series paintings of poplars and Rouen Cathedral, for example, were painted specifically for a one-man show. In early 1883 alone Durand-Ruel staged exhibitions of Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Sisley.

Not that his artists were always appreciative. In answer to one of Monet’s periodic moans, Durand-Ruel was forced to defend himself: “It is not enough to create [masterpieces]. They must be put on display. You think I am not showing your pictures enough ... They are all I am showing; they are all I have concerned myself with for some years now; I have put into them all my heart, all my time and all my fortune, and that of my family.”

Among the other methods used to bolster his artists, Durand-Ruel would sell works through other dealers on a profit-sharing basis, and he did this with collectors, too. He would lend works against business capital and buy his own artists’ paintings at auction to inflate the price. He also opened his own house to visitors on Tuesdays, when the main galleries were closed, so that his collection of impressionist works could be seen. One magazine reported that visitors “invariably left with inflamed eyes”. He also commissioned the likes of Stéphane Mallarmé, Octave Mirbeau and Emile Zola to write the prefaces for his catalogues. And he opened galleries in Brussels and New York as well as Paris, all specially lit to show the paintings to best effect.

It was in fact the US that turned Durand-Ruel’s long-term speculative project into a financial success. In 1885, he received an invitation from James Sutton, director of the American Art Association, to exhibit in New York. Mary Cassatt inveigled her brother Alexander, a railroad magnate and one of the men who financed Grand Central station, into acting as an intermediary. Durand-Ruel sailed with 300 pictures (even though Monet was concerned about seeing his pictures “leave the country for the land of the Yankees”) and found there a new, unprejudiced type of collector eager for impressionist art. “The Americans do not laugh,” said Durand-Ruel, “they buy.” Durand-Ruel is the reason why America has more impressionist works than anywhere else outside France.

The US was his “salvation” and put his business on a sound footing. He would also deal in old masters (the stock book for 1892 shows sales of Van Dyck, Raphael, Canaletto and Tiepolo among others) but, as he had written to Monet, the impressionists had his heart. The painters knew it, too: “We would have died of hunger without Durand-Ruel, all we impressionists,” said Monet. “We owe him everything. He persisted, stubborn, risking bankruptcy 20 times in order to back us.” Renoir, the painter who was as much the dealer’s friend as a client, put things more poetically: “Durand-Ruel was a missionary. It was our good fortune that his religion was painting.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion