On August 14, 1872, The New York Times ran an obituary for the Mexican president Benito Juarez, who had “succumbed to the consequences of a violent attack of neurosis.”

It was one of the first times that the word neurosis appeared anywhere in the paper. First coined around a century earlier by the Scottish doctor William Cullen as “a functional derangement arising from disorders of the nervous system,” the term was a woefully imprecise one; Juarez had, in fact, died of a heart attack.

It would be a few more decades before neurosis came to be strongly associated with the field of psychology. World War I gave rise to war neurosis, now understood as post-traumatic stress disorder, while Freud’s essay Neurosis and Psychosis helped to turn it into a diagnosable condition—but even then, it remained vague, a sort of catch-all for problems of the mind.

Like our understanding of mental health, the vocabulary used to describe it is fluid, with certain terms falling in and out of favor as we discover new ways to diagnose, treat, and think about the various conditions that can arise in the human mind.

A new report from the research firm Fractl examines the ways in which these words have changed over the past 200 years. For the report, researchers looked for appearances of 21 mental-health-related terms in the Corpus of Historical American English, a collection of 115,000 texts from 1810 to the present, totaling around 400 million words. For each term, they also examined the 10 words that most often appeared nearby.

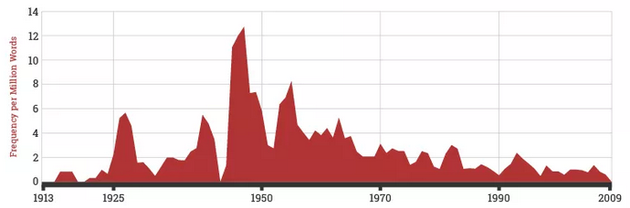

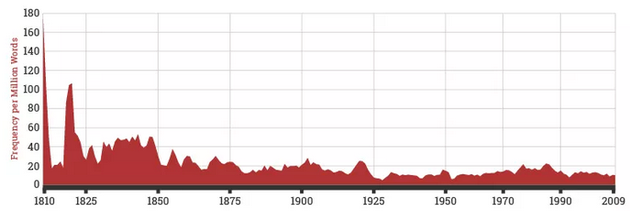

Prevalence of “Neurosis” in American English

Words Most Often Used in Proximity to “Neurosis”

When neurosis was at its height in the 1950s, according to the report, “clinical terms such as mental, obsessional, psychosis, and the plural psychoses were mentioned in the same breath”—but by the late 1990s, the availability of more specific diagnoses had replaced the various types of neurosis. Today, it seems that its utility as an umbrella term had reached its logical end: When a person has neurosis, he’s most often described as having many of them.

Speaking of which, the term mental health is itself a relatively new invention:

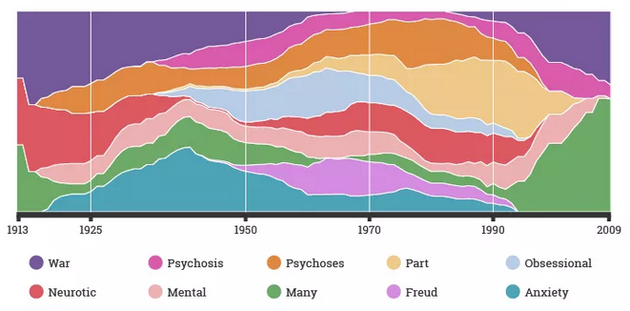

Prevalence of “Mental” in American English

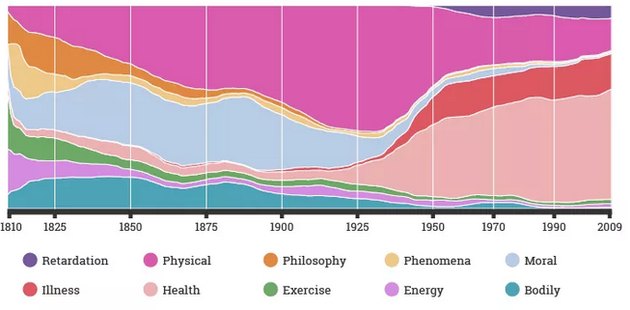

Words Most Often Used in Proximity to “Mental”

According to the Wellcome Trust, the rise of the term mental health was largely due to the efforts of early 20th-century social reformers, who wanted to reduce the stigma attached to people who had been deemed mentally unwell. Whereas mental illness set up a verbal division between the healthy and the sick, the term mental health implied more of a continuum, a state that could improve or degrade in anyone over time.

If mental health is one of the newest tools that modern English has for describing the condition of the mind, then madness is one of the oldest.

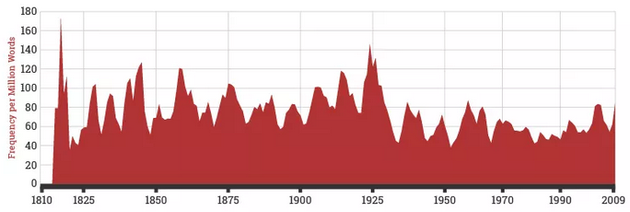

Prevalence of “Madness” in American English

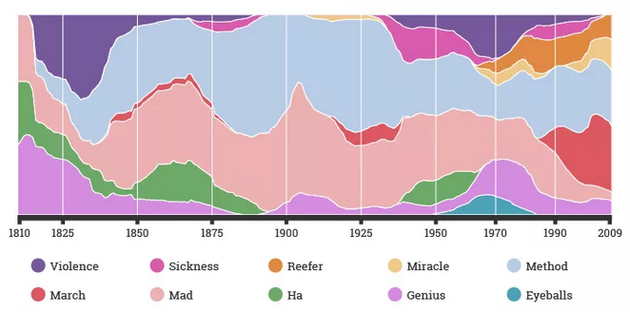

Words Most Often Used in Proximity to “Madness”

The word mad has been used to mean insanity or dementia since the 1500s, but over the past couple centuries, it’s been been used more as a general descriptor of a concept or personality than an indicator of mental illness: “Writers have speculated about potential links between genius and madness and lamented the madness of violence,” the report reads, and “in certain books, villains are portrayed as mad.” (Based on the frequency of the word ha, it seems those villains apparently have a tendency to laugh maniacally; from the 1950s through the 1980s, they apparently also conveyed their villainy through their eyes.)

In recent years, though, two of the most popular uses of madness haven’t had to do with psychology at all, but rather drugs and basketball: madnesses reefer and March, respectively.