How to Stop Seasickness, According to Ocean Explorer Jean-Michel Cousteau

It’s summertime, and you’re looking for any excuse to get on a boat. Booze cruise, sunset sail, or fishing charter, a day at sea is liberating for sure -- until you get seasick and liberate the contents of your stomach over the rail. When I got seasick as hell, I thought death was the only cure.

Only lately, when I met the legendary Jean-Michel Cousteau, was I convinced otherwise.

I was giddy to meet the guy, having declared as I kid that I’d one day become a marine biologist (it never happened), inspired by reruns of his father’s TV program from the ‘70s: The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. Jacques Cousteau, forever nicknamed The Captain, invented the Aqua-Lung during WWII -- the origins of scuba diving as we know it. Perpetually capped by an iconic red beanie, the inspiration for Wes Anderson’s eccentric Steve Zissou in The Life Aquatic, he embodied an intrinsic curiosity for the underwater universe. Whether in command of his famed exploration ship, the Calypso, or producing dozens of documentaries, including multiple Oscar-winners, Jacques Cousteau exposed us landwalkers to what lies beneath the surface, an alien environment with which we are forever entwined, and unquestionably dependent upon, for life on earth.

Now, just imagine what it was like growing up as that man’s kid.

“He threw me overboard at the age of 7 with just a tank on my back,” Jean-Michel Cousteau tells me in the Cayman Island outpost of his Ambassadors of the Environment program. I had zipped down to the Caribbean to learn more about JMC’s global education initiative on ocean conservation. By partnering with select Ritz-Carlton properties, Cousteau’s team can gently encourage affluent guests to return home with a love for ocean life, even when they’re surrounded by concrete.

It’s naïve to think JMC simply followed in his father’s footsteps. He’s got even more years (over 70) of ocean exploration under his belt, during which he’s produced more than 80 films (winning an Emmy, a Peabody, and the Sept d’Or along the way), and founded his immensely respected Ocean Futures Society. While his father was a late-blooming environmentalist, conservation has always animated JMC: He even convinced George W. Bush to declare a 1,200-mile chain of Hawaiian islands a Marine National Monument, which in 2006, was the world’s largest marine protected area.

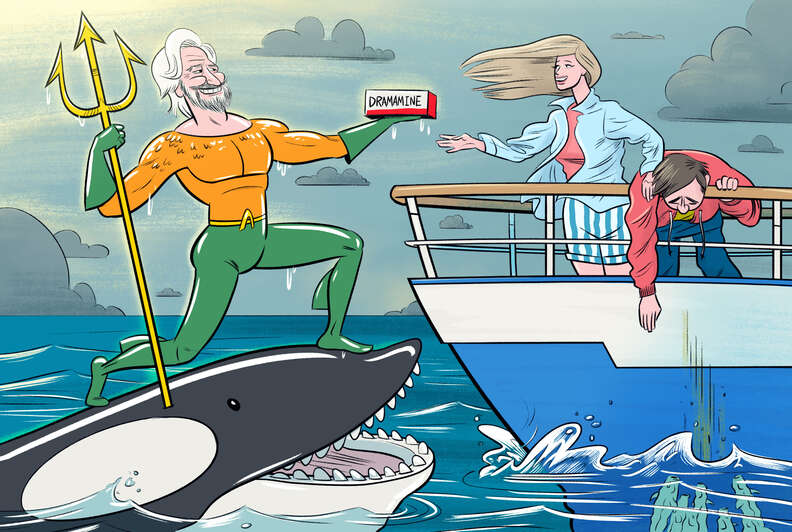

All of that’s wonderful. But when I sat down with this living Aquaman, I really just wanted to know -- on your behalf, dear reader -- how to keep from barfing my ever-loving guts out the next time I’m at sea. Here’s what the dude told me.

Never been seasick? You lucky dog

Seasickness is good ol’ motion sickness, but you’re on a boat instead of a plane or car. It results from a physical miscommunication: your inner ear’s equilibrating responsibilities can’t reconcile the motion of the ocean with your (often static) line of sight. Expect intense nausea, dizziness, and a cavalcade of vomit. “You have to balance your inner ear,” Cousteau says. “It’s usually those who don’t have much practice on a boat that get seasick.”

Noted. Need more friends with boats for “practice.”

Not everyone gets seasick

In more than three-quarters of a century traversing the oceans, Monsieur Cousteau doesn’t recall ever getting seasick himself. I wasn’t surprised, considering his saltwater upbringing. Still, he’s seen plenty of it from passengers on his expeditions. “It happens with others, of course,” he said, magnanimously.

The easiest way to avoid sickness is to avoid turbulent seas

Choppy water and high swells are a recipe for seasickness, and the Pacific Ocean is notorious for those conditions. “Point Conception, near Santa Barbara where I live, you get big swells and winds the rock the boat,” he says. I ask if larger ships are a safer bet for those prone to getting sick, and it becomes clear that’s the wrong question. “Those things that we’re seeing today with 3,000 passengers? You feel disconnected from the ocean,” Cousteau says. “You can be in the middle of one and not even see the water. When I give lectures on cruise ships, I tell them to go immediately to see the water.”

The good news is, there are several ways to head this stuff off

“Some people take pills to to prevent it, others find a way to adapt on their own,” Cousteau says. Dramamine is the default medication to prevent general motion sickness, but sometimes people take too much. Same goes for Cinazzerine, an antihistamine that inhibits vomiting. “They stay sick, but now they’re drowsy and tired and miss the experience!”

The Scopolamine patch is celebrated for providing three-day relief, making it the best option for longer voyages, though it requires a prescription. Others swear by the Sea-Band, a natural method that uses acupressure for nausea relief through a tight-fit reusable wristband. You avoid the potential side effects from taking drugs, but it might be less effective. Whatever treatment you choose, the universal piece advice for seasickness prevention is to stay sober. Booze/pot messes with your equilibrium on land (ever had the spins?), and they’ll definitely not help you on an oscillating surface.

If you missed the boat on prevention, just “feed the fish”

Seasickness is unpredictable, so what do you do when it hits? “Avoid the bow,” he says, referring to the front of the ship, “but the worst thing to do is hide in the gally, where you’re in a torture chamber.” Whatever you do, don’t go below decks to wait it out. Remember that tension between what your ear feels and what your eyes see? It only gets worse when you’re in an enclosed room.

“We see people coming out green in the face,” Cousteau tells me. “They’ll feel better if they just feed the fish.” I interpreted that literally for a second, until I realized it was nautical-speak for throwing up over the side of the boat.

If you find yourself in motion-sickness hell, it becomes mind over matter

JMC believes a psychological approach is best, that creating a sense of wonder for the ocean can cure anything. “What’s most important is getting them to think about their connection to the ocean,” he says. “Suddenly, instead of not feeling well, they’re distracted by our profound connection to the oceans.”

Case in point: while celebrating his 80th birthday this year, a few passengers fell ill as the boat hit a big swell around the same time they were spotting a mother and calf gray whale. He distracted them with narration on the beauty of these massive, yet increasingly endangered creatures. “When they saw the whales the focus shifted with amazement and you stop focusing on anything else,” he recalls. “They were grateful afterwards.”

Cousteau’s final advice: Make like a Cousteau and get into the water

“Just get into the ocean,” he says. “You’re best protected there, since salt preserves.” I glance a photo on the wall of JCM diving, and point out the scuba tank attached to his back. To me, it looks futuristic. He assures me it’s as classic as it gets. “I’m French,” he says, “so there are two tanks in there: one with air, and one with wine.”

Sign up here for our daily Thrillist email and subscribe here for our YouTube channel to get your fix of the best in food/drink/fun.