Anthony Hammond was screaming racial slurs in the parking lot of a California apartment complex before he pulled out a machete and stabbed an African American man, according to police.

The horrific Saturday night attack – which led to hate crime, assault and mayhem charges against the 34-year-old white suspect – received very little attention in US media during the Memorial Day holiday. Also lost in weekend news was the case of a white man in a pickup truck who police say intentionally ran over and killed a 20-year-old Native American man.

The lack of press for both racially charged attacks could be due to the fact that the nation was still reeling from news of a double murder in Portland, Oregon, in which a man stabbed three people who were reportedly trying to stop a racist attack on two young Muslim girls.

The series of attacks in one weekend, along with a threat from a Republican lawmaker to shoot his colleague amid an immigration battle, offer a stark portrait of the racial violence and hate speech in America that activists say have grown since Donald Trump’s election. From Washington state to Texas, the holiday meant to honor fallen soldiers was marred by gruesome assaults during a presidency that critics say has normalized white supremacy and emboldened bigots.

“Trump supporters are now feeling legitimized in their hatred and wanting to act out further,” said Ryan Lenz, senior investigative writer with the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which has tracked a rise in hate groups and incidents during Trump’s campaign and since his inauguration. “It speaks to a climate of hate and intolerance across the country. These three are not isolated.”

Although these three days offered a particularly grisly image of racial violence, these kinds of attacks and outbursts in public spaces are becoming increasingly common, according to studies.

The SPLC collected more than 1,300 “bias incidents” involving harassment and intimidation from the November election through 7 February. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University found a 6% increase in hate crimes in 2016 in US cities and has noted sizable increases so far in 2017 in some metro areas, according to director Brian Levin.

The macabre weekend began on Friday afternoon when police say 35-year-old Jeremy Christian began yelling racist remarks while riding the train in Portland, a west coast city known as a progressive haven. When three passengers tried to intervene, Christian allegedly stabbed them, killing 53-year-old Ricky John Best and 23-year-old Taliesin Myrddin Namkai Meche. Namkai Meche’s last words were reportedly: “Tell everyone on this train I love them.”

A top Republican in the city later told the Guardian he was considering using militia groups as security for Republican events. In Portland, rightwing activists have planned upcoming “free speech” rallies that are aimed at promoting the “alt-right” views that Christian reportedly espoused.

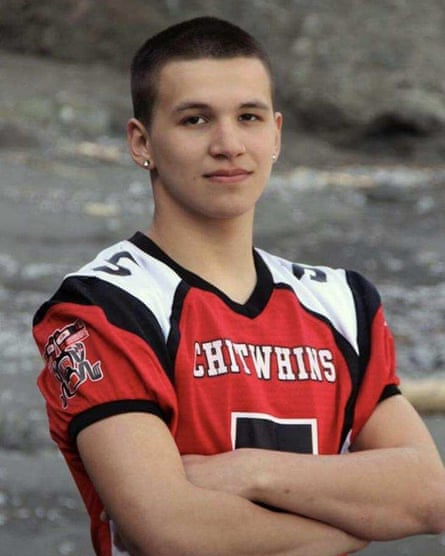

About eight hours after the Portland attack and 150 miles north, Jimmy Kramer, a member of the Quinault Indian Nation, was celebrating his 20th birthday with a group of roughly 10 friends by a river in Washington state. The gathering of teens and young adults, many of them Native American, was interrupted after they sang happy birthday to him and were gathered by a campfire, witnesses said.

A white man in his 30s drove his pickup truck toward the group and eventually, police said, intentionally ran over Kramer, who later died from his injuries. A friend, 19-year-old Harvey Anderson, was also hit, but survived.

“The truck just took off toward us. He was trying to hit us all,” witness Tom Anderson, Harvey’s younger brother, told the Guardian. “There are some cold-hearted souls out there.”

The Quinault Nation said in a statement that the driver was “screaming racial slurs”. In an interview Tuesday, Larry Ralston, Quinault tribal treasurer whose daughter raised Kramer, said he had heard from witness accounts that the driver also made “war whoops” meant to mock Native Americans and that he told them: “You guys don’t belong here.”

David Pimentel, of the Grays Harbor sheriff’s office, said police have been unable to confirm reports of racial slurs and are investigating the hit-and-run as a homicide. But he said the physical evidence and witness testimony suggested “without a doubt” that the fatal collision was intentional.

Maranda James, the Quinault member who raised Kramer, said racism against Native Americans is common in the area. At sporting events, youth are routinely taunted as “dirty Indians”, she said, noting that she once heard a man mock her identity at a local parade.

“It’s unbelievable that it could escalate to something like this,” said James, later adding, “Trump supporters might be a little more outspoken now because he’s president.”

Many are struggling to come to terms with the possibility that the attack was racially motivated, she added: “Just to know somebody intentionally did this, it’s even harder to deal with if it’s a hate crime.”

Ralston said he was constantly tormented for being native when he was young: “It’s just the stereotyping that’s always been there.” Trump’s agenda may be making things worse, he added: “This has been a motivation to start another race war.”

One day after the violence in Washington, police in Clearlake, California, 80 miles north of San Francisco, responded to calls of the stabbing by Hammond, who retreated to his apartment, leading to an hours-long standoff. He was eventually arrested and held on a more than $1m bond, the Associated Press reported. Police said the victim was stabbed in the shoulder and suffered “serious bodily injury”.

A day later, violent threats and physical confrontations broke out at the Texas state capitol after a Republican lawmaker Matt Rinaldi said he called federal immigration authorities on undocumented protesters. A shoving match with Democratic lawmakers reportedly followed, and Rinaldi was later accused of telling one of them he would “put a bullet in your head”. The lawmaker said in a statement that his Democratic colleague Poncho Nevarez had threatened him and that he had told Nevarez he would shoot him in self defense.

Some said it was hard to separate the weekend’s violence from the rhetoric of Trump who has bragged about sexual assault, joked about attacking his opponents and protesters and made racially prejudiced remarks about Muslims, Mexicans, African Americans, indigenous people and other minorities.

For some of the loved ones of the weekend’s victims, it’s difficult to make sense of such random violence.

Cory Smith, who also helped raise Kramer, said he didn’t know if race played a factor in the killing. Kramer, a fisherman and father of two baby twins, was a “big-hearted kid, loving and kind, the type who would take his shirt off his back for everybody”, said Smith, noting that many believe he jumped in front of the car and took much of the impact to protect his friend.

“He saved another kid’s life,” he said. “Some people are looking at him as a hero.”