Coming to Terms With My Father's Racism

How to find the fragile middle in a time of racial tension

My earliest memories of my father’s racism are rooted in the family dinners of my childhood.

Dad sat to my left, always. My mother sat across from me, with my little brother seated to her right. My two younger sisters sat at opposite ends. In the 1960s, our table was metal, and small. There was no escaping whatever was on our father’s mind.

I cannot quote verbatim his tirades, and I am grateful for that small mercy, but I remember his tone with a bone-deep weariness. Raised voice, fist on the table. He was angry with black people for reasons that depended on his day at the plant, a song on the radio, a story he’d read in the afternoon paper. To this day, I hear the n-word and can see the contortions in his face.

Most daughters want to be daddy’s little girl. This aspiration was lost on me at an early age. I loved my father, always, and feared him too often, but by age 6 or so I knew there was something wrong about him. He would rant about black people he’d never met, and I would see the faces of my classmates, my friends. Silently, I’d pick at the fried Spam or pile of goulash on my plate and think about Sandy and Gary and Valerie and Phillip, and sometimes my eyes would sting. It was not the natural order of things to be so young and know your father had no idea what he was talking about.

I live in Cleveland, where a 12-year-old black boy named Tamir Rice was recently shot and killed by a white police officer. The community at large professed outrage, but when I attended his public funeral it was filled with black mourners, and I left wondering if maybe most of us white people think this isn’t our problem anymore. After weeks of reading and moderating public comment threads about the deaths this year of Tamir and two other unarmed black males, Michael Brown and Eric Garner, I can’t ignore this dark and familiar something clawing at my heart.

There are moments when it feels like we’re inching back toward the 1960s, but back into communities that are far more segregated, by race and means. If you are black and poor, you can now spend your entire childhood knowing only other poor, black children. If you are born lucky and grow up surrounded by mirror images of your good fortune, it’s easy to see yourself as a majority stakeholder in a world primed to do your bidding.

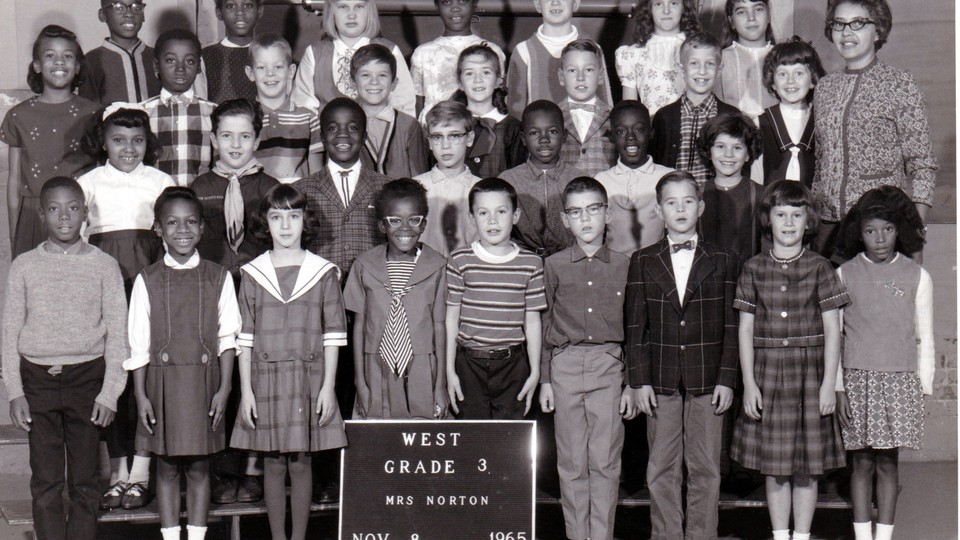

Last week, I walked down to the basement of my home to dig up class pictures from my elementary-school days. I haven’t looked at those faces in 20 years, I’ll bet, but I could summon the names of just about every child in them, and the complicated memories that tag along.

There we are, lined up shoulder-to-shoulder on risers in the basement of West Elementary School, hands to our sides, faces wide. In each picture, half of the class is black. Those black faces, as surely as the color of my eyes and the gaps between my two front teeth, are evidence of my roots. At the same time, they telegraph the lifelong struggle of my father, who for so long saw their existence in my life as a failure in his.

I grew up in Ashtabula, a working-class town of 20,000 people an hour east of Cleveland. Mom stayed home with us in the early years. Dad worked for the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company on Lake Erie’s shore. His job made him big and strong and often angry for reasons we didn’t understand. He worked in maintenance. Until I was 10, I thought that meant he was a custodian, when in reality he held one of the most skilled jobs at the plant. We were raised to understand that our father went to work so that he could take care of us. Our curiosity ended there.

We lived in a rental house on U.S. Route 20, on the integrated side of town. The West End, we called it. The house is still there, and has been boarded up for years. Our street was all white, but the short walk to school delivered me to classrooms evenly divided between white and black kids. In second grade, we had eight black kids, seven white. By fourth grade, the numbers jumped to 15 each. My third-grade teacher, Mrs. Norton, was black. This was a big deal in my neighborhood. My mother often mentioned that Mrs. Norton had a lot of class, but she said this only to her girlfriends. Never at the dinner table.

I grew up surrounded by children who didn’t look like me, and my only problem with that, aside from the constant tension with my father, was that I wanted to be them. The girls were my confidants, my touchstones. We played with each other’s hair and swapped barrettes and ribbons like boys trading baseball cards. I loved their music, from the Motown on their kitchen radios to the gospel songs in their churches, where worshippers praised God like they knew him, instead of sitting ramrod-straight week after week waiting to make his acquaintance.

I loved their mothers, too. Ours was not an “I love you” kind of home, and I melted in the arms of these women who called me “child” and “honey” and always ordered me to sit at their tables for after-school snacks. Surely they noticed that their children were never invited to my home, but I never felt they held that against me.

My father had no idea that I visited my black friends’ churches or stepped foot in their homes. I don’t remember my mother ever saying we were keeping our secrets. The conspiracy was implicit; the necessity understood.

Here begins the long list of excuses I’ve made for my father in my head all of my adult life.

He grew up on a farm in Northeast Ohio, surrounded by other white, rural folk, many of them family. By his lights, the high point of his life was his senior year in high school, when the local newspaper heralded him as one of the best point guards in the state. I have his scrapbook from that year. It’s full of yellowed newsprint and black-and-white glossy photos starring a skinny hotshot with sweaty red hair from Nowhere, Ohio. I have his collection of felt varsity letters, too. Nearly 60 years old, and in pristine condition.

My father had a chance to go to college on a basketball scholarship. I learned this only after his death, when my sisters found the letter from the university’s basketball coach. He never mailed in the appointment card, never used the bus ticket. Instead, Mom became pregnant with me, and Dad got a marriage license and a union card the same year. By the time he was banging his fist on the dinner table in 1963, he was still four years from 30 and the father of four. Everywhere he looked, he saw his missed opportunities blooming in someone else’s life.

When I started junior high school in 1969, my father and I were arguing all the time, sometimes about boys, occasionally about hemlines, but usually about race. He was full of contradictions. He liked a black guy at work, but that’s because he didn’t “act black.” He loved The Supremes until I played them constantly, at which point he set a limit on how many black artists’ records I could buy with my babysitting money. One a month, tops. He smashed my 45 of Aretha’s “Respect” into a pile of pieces when I violated the rule.

The timing of his attempt to rein me in couldn’t have been worse, because everything was changing at school. Within days of my seventh-grade year, the kids who had come from the all-white elementary school on the other side of town took note of my companions at the lunch table and started calling me a n— lover. The kids from the mostly black elementary school badgered my friends for hanging out with the white girl. The same mothers who used to pull me to their bosoms now acted like they didn’t see me in the hallways and at Friday-night games, and nodded terse hellos to my parents.

My father saw a glimmer of hope in my feelings of abandonment. So much for friendship. Blood’s thicker than water. Guess you’re learning that God made us different for a reason.

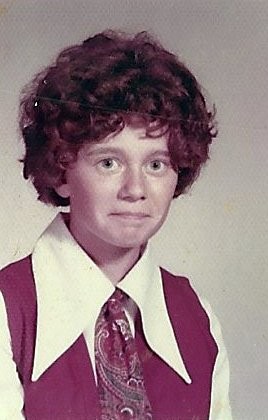

I had spent most of my childhood identifying with children who did not look like me, and in a fit of pubescent angst, decided it was time to change that. A week before school pictures, I talked a neighbor lady into cutting my long hair and giving me a white girl’s Afro with a Toni perm.

My mother collapsed on the sofa and fanned her face with her apron. My father refused to be seen in public with me. When he found out I had a crush on a black boy, he grounded me for weeks. I bought tubes of QT and worked on my tan.

My father and I were at war.

By the time I was a senior in high school, in the fall of ’74, my dad had finally managed to save enough money to buy a house on the white side of town. For the first time, I had my own room, and he took me to Sears to buy a bedroom set. A peace offering, but détente was temporary. I left for college and joined the school newspaper. I was back at it, this time with an audience. After a disastrous sophomore summer home, he ordered me to live elsewhere, and I happily complied.

If the story ended there, at the gulf of our divisions, I would feel no hope now in these troubled times. I would look at those class pictures from my childhood and see a failed experiment in good intentions. I’d have to tell myself that some white people, white people like my father, are just unreachable.

For years, I wondered: How good is a daughter’s liberation if her father only sees it as his failure? Where’s the victory in that? Maybe it’s enough for those who don’t care what their father thinks, but I always did. I didn’t want his approval. I wanted his agreement that he’d been wrong all along about black people. More to the point, I wanted him to admit he’d been wrong about me.

I wish I could say I stayed true to my roots in a rocket-straight trajectory from that first-grade picture to today. I raised my two children in diverse school systems, deliberately so, but after they graduated from high school I just as deliberately spent eight years in an all-white suburb on Cleveland’s west side. I didn’t move there because everyone looked like me—I had married then-U.S. Representative Sherrod Brown, and we had to live in his congressional district—but I should have known that a lifetime of something else would render me a hypocrite under the circumstances. If I’ve learned anything about myself in the last few years, it’s that somewhere inside me resides a five-year-old capable of delivering withering criticism. A child remembers, always.

Last year we moved into the city of Cleveland, where I’ve worked as a journalist for more than 30 years. I can’t run to the drugstore or fetch a loaf of bread without crossing paths with faces that remind me of what I came from—of who I came from, I should say. Some suburban acquaintances have questioned our move with various versions of the same indictment: What were you thinking? Always, I am able to answer: Home. I was thinking of home.

My father died in 2006. He lived seven years longer than my mother. She never got in the middle of our fights about race, but it was her short illness and death, at 62, that helped us find our way to a fragile middle.

The turning point arrived without warning in a hospital waiting room.

It was late August 1999. My mom was weeks from dying. Dad and I were a tag team of concern. We spent our days sitting in offices and waiting rooms, sometimes with Mom, sometimes without her. Over and over, my father would whisper to me, “This should be happening to me. I should be the one who is dying.”

On this particular morning, Dad and I sat wedged together in a packed room, our backs against a wall. We were waiting for Mom, again.

To get to this place, this moment, we had walked behind the black orderly who pushed Mom’s wheelchair down the hall. We had thanked the black receptionist who directed us where to sit. We had just nodded hello to the black resident who always made my mother smile.

My father leaned his head against the wall and closed his eyes.

“God,” he said, “they’re everywhere now.”

I clenched the armrests and tried to control my breathing as I turned to look at him. Tears pooled at the corners of his eyes. For the first time ever, he reached for my hand.

We started there.