Hours Before Campaigning With Obama, Clinton Tries to Distance Herself on Education

The presumptive Democratic presidential nominee wants to stick close, but not too close, to the president’s legacy.

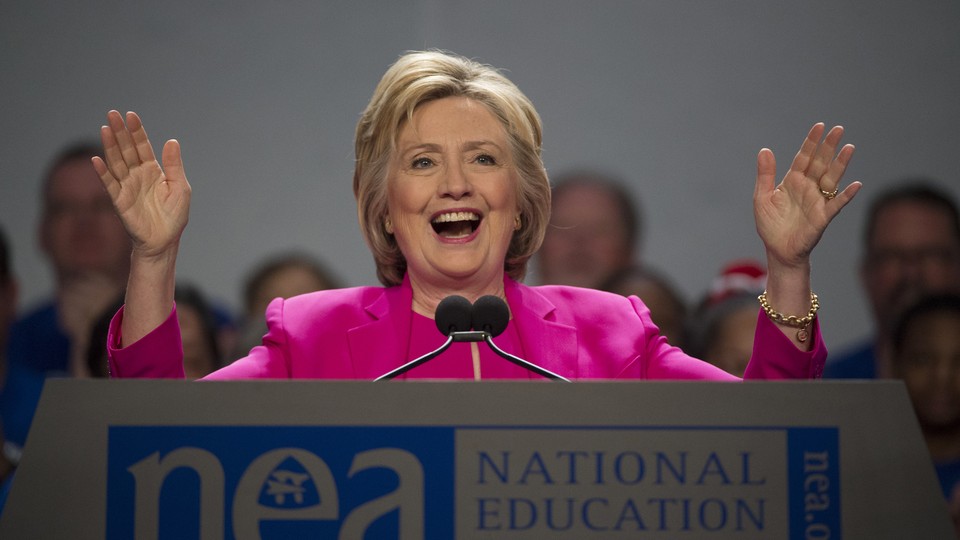

Hillary Clinton used her address at the National Education Association’s annual meeting as an easy opportunity to criticize Trump for failing to support students. Her attempt to distance herself just enough from President Obama to attract teachers, but not so much as to alienate his supporters, proved a more challenging balancing act.

Speaking to more than 7,000 members of the largest labor union in the United States, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee said, “It is time to stop focusing on, quote, failing schools. Let’s focus on all our great schools, too.” Standardized testing, Clinton added, should go back to its “original purpose” of helping teachers and parents figure out which kids needs support.

The comments sounded innocuous enough, but they generated some of the loudest cheers during Clinton’s half-hour speech. Teachers have been among the harshest critics of the Obama administration’s push to identify, and they contend, ostracize, consistently low-performing schools, and the remarks gave some NEA members hope that a Clinton administration would be more friendly to educators. Teachers sometimes felt like they were being punished under Obama, said Sue Cahill, a kindergarten teacher from Marshalltown, Iowa, who said she walked away from the speech thinking a Clinton presidency “would be different.”

That’s exactly what the Clinton camp would like to hear. But Clinton, who boarded Air Force One with the president for a campaign stop in North Carolina immediately after her speech, also disappointed some of the union’s three million members when she said that as president, she would look to both charter schools and traditional public schools for models of what is working in education. “Let’s sit at one table,” she said. “We’ve got no time for all these education wars.” The line didn’t go over so well. The Obama administration has been viewed by many union members as too cozy with charter schools, and Clinton’s comments seemed to do little to allay the fear that she would continue that pattern. Just after Clinton’s remarks, Lily Eskelsen Garcia, the union’s president, sought to explain the negative reaction to the charter comments by telling several reporters that “the anger comes from...for-profit charters,” which the union has accused of sucking badly needed funding from neighborhood schools.

While Cahill and a number of other NEA members said they were ultimately eager to back Clinton, she hasn’t won over others, including a science teacher from Seattle named Noam Gundle. The high-school biology instructor said he supported Bernie Sanders over Clinton because of the senator’s “progressive” education beliefs and ability to organize. He distrusted Clinton’s relationship with various education foundations, he said, and was upset with the NEA for backing Clinton prematurely.

Gundle isn’t an anomaly. Clinton earned the union’s endorsement last fall in a move that prompted some chapters to refuse outright to support the endorsement and fueled accusations that the union didn’t adequately consult its members ahead of time. But other members said the NEA’s failure to endorse a candidate in the 2008 presidential primary was a cautionary lesson. That decision, they argued, allowed the Obama administration to expand charter schools and high-stakes testing. Eskelsen Garcia said Tuesday in response to a question about the early endorsement that the decision “passed overwhelmingly.”

While Gundle, who called Trump the “biggest danger to our country in 100 years,” said he will cast a ballot for Clinton in November, he won’t be doing so eagerly. “I think that we ought to be holding their feet to the fire,” he said of the candidates. The lack of enthusiasm for Clinton among teachers who had high hopes for a Sanders nomination could make mobilizing the union’s 3 million members a serious challenge. But Jaim Foster, a kindergarten teacher in Arlington, Virginia, said it was time for union members to put aside their differences and come together to elect Clinton. The union in his area has been going door-to-door and waging a social-media campaign to rally members behind the candidate, he said. Nikki Woodward, an early-childhood educator from Gaithersburg, Maryland, said local members have been organizing “phone parties” to call colleagues and urge them to vote.

The hope among supporters is that, even if they can’t be convinced to actively call for Clinton to win, fear of a Trump victory will drive some turnout among less-than-enthused members. Cahill, the Iowa teacher, recalled a 2006 immigration raid on a meatpacking plant in her town that she said rattled the community. “That’s what I fear is the alternative.” But negativity isn’t generally as good for turnout as actual enthusiasm, and, as Trump and his supporters have pointed out correctly, he’s successfully mobilizing people who don’t typically vote.

Eskelsen Garcia knows this. “This election has to be about so much more” than the Anyone But Trump movement, she said as she introduced Clinton. “Hillary sees our students as whole human beings, not as test takers.” Whether she can mobilize members behind that notion is still up for debate.