In the first instalment of this lecture, Reverend Okumura explained that `zazen is an acupuncture needle to heal the sickness caused by the three poisonous states of mind. Because the sickness is inveterate and obstinate, it is very difficult to heal. Even though our practise of zazen, being based in Buddha’s teaching, is a treatment of this sickness, our zazen itself can be a poison and cause sickness. Our way-seeking mind can be very deeply influenced by the three poisonous states of mind. This is a strange contradiction, isn’t it? In order to practise to be free from the three poisonous states of mind, we need the three poisonous states of mind. This is the most important koan for us: How can we continue to practise going through this contradiction? How can we go through this contradiction and continue to practise? How can we be free from this samsara within our Buddhist practice, within our zazen practice? I think that this is the sickness Dogen Zenji discusses in Shobogenzo: Zazenshin. How can we cure this sickness? This is the main point of Dogen’s poem Zazenshin.’ In this instalment of his commentary on Shobogenzo: Zazenshin, Reverend Okumura speaks about his experience in relation to this teaching.

My experience

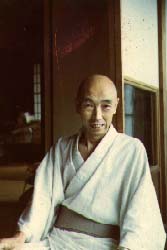

I first read a book written by my teacher Kosho Uchiyama Roshi when I was seventeen years old. Somehow I wanted to be his student. I knew nothing about Buddhism or Zen, but somehow I wanted to live like him. I started to practise zazen when I was nineteen. Because I knew nothing about Buddhism, Zen or Dogen’s teachings, I went to Komazawa University to study Buddhism and Dogen. When I was twenty, I sat my first five-day sesshin at Antaiji, where Uchiyama Roshi lived. Eventually, when I was twenty-two, I was ordained.

I first read a book written by my teacher Kosho Uchiyama Roshi when I was seventeen years old. Somehow I wanted to be his student. I knew nothing about Buddhism or Zen, but somehow I wanted to live like him. I started to practise zazen when I was nineteen. Because I knew nothing about Buddhism, Zen or Dogen’s teachings, I went to Komazawa University to study Buddhism and Dogen. When I was twenty, I sat my first five-day sesshin at Antaiji, where Uchiyama Roshi lived. Eventually, when I was twenty-two, I was ordained.

The sesshins at Antaiji were unique. One period of zazen was fifty minutes. We also had ten-minute kinhin. We woke up at 4:00 in the morning. We sat two periods before breakfast, then we had breakfast and a short break afterwards. We then sat five periods in a row, from 7:00 a.m. until noon. We had lunch at noon and another short break. We then sat five periods in a row from 1:00 to 6:00 p.m. We had supper and a short break, and then we sat again for two more periods from 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. We sat fourteen periods a day. We had no services, no lectures, no work periods, nothing.

January in Kyoto is very cold. I was a twenty-year-old university student at my very first sesshin and I was cold and in pain. For the first few years, to sit in this zazen posture was nothing other than to have pain. It was very painful. Not only that, I was extremely sleepy. While I was in Tokyo going to school, I read books until midnight or even early morning and often slept until almost noon. When I went to Antaiji and experienced the sesshin schedule, I felt like I was suffering from jet lag. Day and night became nearly opposite of what I had been used to in my daily routine. It was cold in the zendo. It was painful to sit and I was very sleepy. It was a rather discouraging experience for me.

When the sesshin was over, I thought it was the first and the last sesshin for me. But after I returned to Tokyo, I felt like the sesshin and the temple were where I was supposed to be — not in the cold zendo, but sitting on the cushion. I didn’t understand why I felt this way. After that sesshin, even though I still didn’t have much knowledge about Buddhism or Zen, I felt that was the place I should return. After this experience, I felt like I must have been in a dream since my birth until that point. During that sesshin, even though it was not an easy practice, I felt like I woke up from my dream for the first time. I didn’t know why I felt this way. I didn’t understand what the experience was at the time, but somehow, this sitting practice became the most important thing in my life. Since then, I have been practising zazen for more than thirty years.

When the sesshin was over, I thought it was the first and the last sesshin for me. But after I returned to Tokyo, I felt like the sesshin and the temple were where I was supposed to be — not in the cold zendo, but sitting on the cushion. I didn’t understand why I felt this way. After that sesshin, even though I still didn’t have much knowledge about Buddhism or Zen, I felt that was the place I should return. After this experience, I felt like I must have been in a dream since my birth until that point. During that sesshin, even though it was not an easy practice, I felt like I woke up from my dream for the first time. I didn’t know why I felt this way. I didn’t understand what the experience was at the time, but somehow, this sitting practice became the most important thing in my life. Since then, I have been practising zazen for more than thirty years.

I was ordained by Uchiyama Roshi in 1970 when I was twenty-two years old. I was still a university student. I wanted to quit school, but my teacher asked me to finish school before starting to practise at Antaiji as a training monk. At Antaiji, we had sesshin as I described above ten times a year. I practised there until Uchiyama Roshi retired in 1975. I was among three of his disciples that he sent to this country. I lived in Massachusetts with two of my dharma brothers for five years and we practised as we did at Antaiji. We had a five-day sesshin every month there, twelve times a year.

To have a five-day sesshin each month means that every three weeks I had a sesshin. We sat from 4:00 in the morning until 9:00 in the evening every day for five days. Eventually, I had to go back to Japan in 1981 because my body was half broken from too much work clearing the land and digging a well. But I continued to practise in this way until 1992 in Kyoto, Japan. I really did practise just sitting for more than twenty years. I sat more than two hundred sesshins. Zazen became the centre of my life. I lived within zazen or I lived between sesshins.

Zazen is, still now, the most important thing in my life. To understand what zazen really is became the most important thing to me. Understanding zazen would mean understanding what my life is. Since I was twenty years old, I have been studying Buddha’s and Dogen’s teachings in order to study what I am doing. Honestly speaking, Dogen’s teaching is very difficult. Many of his writings didn’t make sense at all to me for a long time.

In 1993, I came to America again and I practised and taught at Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, which was established by Dainin Katagiri Roshi. I followed Katagiri Roshi’s style of practice instead of Uchiyama Roshi’s style. That means I gave lectures during sesshin. It was very difficult. Just sitting, in a sense, was much easier. Somehow `just sitting’ (shikantaza) and giving lectures are kind of contradictory. In order to give a lecture, unfortunately, I had to think. Zazen should not be thinking.

Think of not thinking.

How do you think of not thinking?

Beyond thinking.

In our zazen we have to let go of any kind of thinking, even thinking about dharma. Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to prepare lectures before sesshin started. I had to prepare the lecture during sesshin. To be a teacher in that kind of practice was very difficult to me. Please have compassion for teachers.

Although this practice was really difficult for me, it was also very helpful for me. I had to explain everything in English. During sesshin, because I didn’t want to think about something else, I decided to give lectures about Dogen’s writings on zazen. That way I could think about zazen. This is really thinking of not-thinking and beyond thinking! Anyway, since 1993, for almost ten years, I have been practising in this way in this country. Giving lectures became part of my practice.

Though hard, preparing and giving lectures and practising in this way was also very helpful in coming to a clear understanding of the material. When I read Dogen in Japanese and think about his teachings in Japanese, somehow I almost automatically felt that I understood it. However, when I have to explain in English, I have to really clearly understand what Dogen meant. Otherwise, I cannot speak at all. Because English is not my native language and I don’t have a broad a vocabulary, I am often forced to make black or white distinctions. When I speak in Japanese, I can make any kind of grey zone. Even though I don’t really understand, somehow I can say something. But in English, I cannot do such a thing. I have been trying to make my understanding of the writings clear.

Though hard, preparing and giving lectures and practising in this way was also very helpful in coming to a clear understanding of the material. When I read Dogen in Japanese and think about his teachings in Japanese, somehow I almost automatically felt that I understood it. However, when I have to explain in English, I have to really clearly understand what Dogen meant. Otherwise, I cannot speak at all. Because English is not my native language and I don’t have a broad a vocabulary, I am often forced to make black or white distinctions. When I speak in Japanese, I can make any kind of grey zone. Even though I don’t really understand, somehow I can say something. But in English, I cannot do such a thing. I have been trying to make my understanding of the writings clear.

Also, my translation work requires me to be specific about the meaning in each word. It is very difficult because Dogen and Zen writings, in general, use one word to give more than one meaning at the same time within one sentence or within one writing. Now, I think having to address this dilemma during my translation work is my karma. I don’t know if this is good karma or bad karma. But somehow I try to enjoy it and I hope you enjoy this too.

About the text

In this writing, Shobogenzo Zazenshin, Dogen Zenji quoted and discussed three koan stories. In the first part, Dogen Zenji discusses Yakusan’s koan: `Think of not thinking. How do you think of not thinking? Beyond thinking.’ In the second part, Dogen comments on Nangaku’s story about polishing a tile. In the third part, Dogen praises and comments on a poem written by Zen Master Wanshi Shogaku (Ch. Hongzhi Zhengjue) entitled Zazenshin. This poem was the source of Dogen’s title for this part of Shobogenzo. Following these three main sections of his writing, Dogen composes his own poem entitled Zazenshin.

The three parts of this text are very interesting and they are important to understanding the nature of Dogen’s zazen. In 1996, I spoke at length on the first part of this text. During this sesshin I will focus on the second: Nagaku’s story about polishing a tile. As background, I will reiterate points about the first section concerning Yakusan’s dialogue with his student.

Two types of sickness in zazen

In the beginning of this writing, Dogen quotes Yakusan’s dialogue with his student:

The monk asked, `What is thinking in steadfast immobile sitting?’ By this, the monk means, `What is thinking in zazen?’

Yakusan said, `I think of not thinking.’

The monk asked again, `How do you think of not thinking?’

Yakusan said, `Beyond thinking.’ (J. Hi-shiryo)

This koan is quoted in Fukanzazengi, too. Although this verse is also very important to understanding Dogen’s zazen, I will not take the time now to discuss it.

If having buddha nature intrinsically means everything is okay as it is, then why do we have to go through such a difficult, painful, cold, sleepy, and boring practice?

Instead, I will talk about a question Dogen posed following his commentary on this koan. He asked, `What is the sickness of zazen?’ The most important point for us to understand from the first section of Zazenshin is the problem Dogen raises: sickness in the practice of zazen. In a translation of Shobogenzo: Zazenshin that I completed and Taitaku Pat Phelan edited, Dogen writes:

Instead, I will talk about a question Dogen posed following his commentary on this koan. He asked, `What is the sickness of zazen?’ The most important point for us to understand from the first section of Zazenshin is the problem Dogen raises: sickness in the practice of zazen. In a translation of Shobogenzo: Zazenshin that I completed and Taitaku Pat Phelan edited, Dogen writes:

`Nevertheless, these days some careless stupid people say, [This is very Dogen. He’s not a gentle person.] “Practise zazen and do not be concerned with anything else in your mind. This is the tranquil state of enlightenment.” This view is beneath even the views of Hinayana scholars. It is inferior to the teachings of human and heavenly beings. Those who hold this view cannot be called the students of the buddha dharma. In recent Great Song China, there are many practitioners like this. How sad that the Way of the ancestors has fallen into ruin.’

`Practise zazen and do not be concerned with anything else in your mind. This is the tranquil state of enlightenment.’ In this passage, I think Dogen is referring to the mistaken idea that we don’t need to care about anything. Just sit in a quiet place and be peaceful. According to Dogen, that is not zazen based on buddha dharma or Buddha’s teaching. Our practice is not simply enjoying peacefulness or quietness. Dogen is very strongly against this kind of attitude toward zazen. According to Dogen, this is one sickness. It sounds like `just sitting’, but according to Dogen, this is not `just sitting’. He said this is a sickness. This is point number one.

The second sickness is expressed in the following passage:

`Others insist that the practice of zazen is important for beginners, but is not necessarily the practice for buddhas and ancestors. Walking is Zen; sitting is Zen. Therefore, whether speaking or being silent, whether acting, standing still, the body of the self is always at ease. Do not be concerned with the present practice of zazen. Many of the descendants of Rinzai hold this sort of view. They say so because they have not correctly received the true life of buddha dharma. What is beginner’s mind? What is not beginner’s mind? What do you mean when you say “beginners?”’

Dogen here is pointing to the second kind of sickness or mistaken view: In order to attain a certain kind of enlightenment or enlightened experience, we need the practice of zazen, but once we attain so-called enlightenment, then zazen is not important any more. Dogen said that many Rinzai practitioners during his time used zazen as a method or means or step or ladder. Believing that having once attained this enlightenment or some particularly deep experience, you wouldn’t need to practise zazen any more. Dogen addressed the same attitude in question number 7 of Bendowa. This is the second kind of sickness according to Dogen.

I think these two mistaken attitudes towards zazen were what Dogen found in the process of his searching the Way. When he practised and studied at a Tendai monastery on Mt. Hiei as a teenager, he had a question about one of Mahayana Buddhism’s teachings. In this Buddhist teaching it is said all beings or all people have so-called dharma nature or buddha nature. Everything is perfectly enlightened as it is. If this was so, he wondered, then why did buddhas and ancestors have to practise? That was Dogen’s original question. If having buddha nature intrinsically means everything is okay as it is, then why do we have to go through such a difficult, painful, cold, sleepy, and boring practice? I think this question is very much ours, too. This practice of ours is not about a belief that `everything is okay as it is.’ If that were so, then Buddha didn’t need to leave his father’s palace and become a beggar.

After Dogen left Mt. Hiei, he started to practise Rinzai Zen at Kenninji in Kyoto with Myozen. Kenninji was the first Zen monastery in Japan founded by Eisai, the first Japanese priest who went to China and transmitted Zen to Japan. Myozen was one of Eisai’s disciples. I think Dogen found some Rinzai practitioners who insisted that practising zazen was necessary only until someone attained an enlightenment experience; and that after such an achievement, zazen was not needed any more. In other words, this viewpoint held that in order to reach the other shore, we need a raft, but after reaching it the raft should be abandoned. I think this thinking or belief is what Dogen refers to here as the second sort of sickness.

After Dogen left Mt. Hiei, he started to practise Rinzai Zen at Kenninji in Kyoto with Myozen. Kenninji was the first Zen monastery in Japan founded by Eisai, the first Japanese priest who went to China and transmitted Zen to Japan. Myozen was one of Eisai’s disciples. I think Dogen found some Rinzai practitioners who insisted that practising zazen was necessary only until someone attained an enlightenment experience; and that after such an achievement, zazen was not needed any more. In other words, this viewpoint held that in order to reach the other shore, we need a raft, but after reaching it the raft should be abandoned. I think this thinking or belief is what Dogen refers to here as the second sort of sickness.

This attitude is not authentic even in Rinzai Zen. A common mistaken understanding within Rinzai Zen is that to have a certain deep experience, a so-called kensho, is a goal of practice. However, in true Rinzai Zen, the experience of kensho is merely a starting point of practice. According to Dogen, many Rinzai practitioners during his time practised in a mistaken way.

The first kind of sickness is sometimes called buji Zen. Buji means `nothing matters’; and `everything-is-okay’ kind of Zen. The second sickness is the belief or attitude that we need to practise in order to attain enlightenment as some kind of fancy experience, after which everything becomes okay—that we have no problems at all after such an enlightened experience. This is the belief that, at a point, we become so-called enlightened persons. These are two basic sicknesses in Zen practice, according to Dogen.

Dogen tried to offer an acupuncture needle as a treatment to heal such mistaken attitudes by writing this chapter of the Shobogenzo. Misled, our motivation or aspiration or way-seeking mind can be influenced by either `everything is okay, nothing matters,’ or `I need to practise in order to attain something.’ These are two symptoms of the three poisonous states of mind in Zen practice.

This is the second in a series of lectures on Dogen Zenji’s Zazenshin by Reverend Shohaku Okumura during sesshin at Chapel Hill Zen Center in Spring 2001. It was published in the Spring 2004 issue of The Bridgeless Bridge and is reprinted here with their kind permission. Shohaku Okumura is a translator and the founder of the Sanshin Zen Community, Bloomington, USA. In the next instalment, he will talk on the second section of Shobogenzo: Zazenshin, Nangaku’s story of polishing the tile.

Read the rest of, Zazenshin: Acupuncture Needle of Zazen here.

First published in the November 2004 Buddhism Now.

Read some more Zen teachings from Dogen.

Categories: Buddhism, Buddhist meditation, Chan / Seon / Zen, Shohaku Okumura

Outstanding series. Dogen a favorite. He captures Dogen so well. Dogen IMHO saw things that no one else did. He seemed like to turn things around as he examined it.

..Edited…

Loving this series, thank you for posting!