The Importance of Scaring Children

The long tradition of moral ambiguity and unhappy endings in kids' fiction returns with Evangeline Lilly's The Squickerwonkers.

Children’s fiction—in literature and in film—faces a curious challenge: Adults usually write the story, dream up the characters, and try, in a somewhat circuitous way, to teach children lessons they believe children should be taught.

Given that fact, creating scary children’s fiction is an even more curious challenge: Many adult writers pull back from fully covering themes they deem inappropriate or too scary for young readers, by giving their stories happy endings and clearly drawn lines between the "good" and "bad" characters. That way, kids have no confusion about what's right and what's wrong.

"It's an understandable impulse," Deborah Stevenson, the director of the Center for Children's Books at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, says. "We want to protect kids."

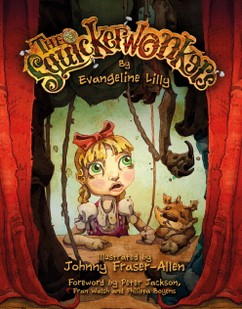

In The Squickerwonkers, actress Evangeline Lilly tries to break the pattern. The book, out Tuesday, is the first in her debut children's series about the adventures of a motley crew of marionette-like beings, each representing a vice: There’s Papa the Proud, Mama the Mean, Andy the Arrogant, and six other members of the Squickerwonkers family.

And these guys are creepy. They’re button-eyed and bursting at the seams. The lone human character, the protagonist Selma, isn’t any better. She looks like a wide-eyed little girl, but her appearance is unnatural, adding to the book’s sinister aesthetic. Lilly’s story is just as eerie: It begins with Selma entering an abandoned wagon before meeting each of the Squickerwonkers. Soon after their introduction, they pop her balloon, and turn her into one of their own, complete with button eyes and strings holding her up—a thoroughly upsetting ending. But that’s just fine by Lilly.

“There’s been a trend for a very long time where children’s storybooks are very careful and very meek and have to have happy endings, but those happy endings are only for good people,” she tells me. “The world isn’t that simple.”

Dark children’s stories aren't new (think Neil Gaiman, Lemony Snicket, or Roald Dahl), but the past few months have seen a resurgence in telling tales for children that blend pure horror with age-appropriate themes. Lilly’s book mixes creepy characters with lighthearted language (the book is written in limericks). September’s The Boxtrolls, based on Alan Snow’s Here Be Monsters!, used cartoonish character design to offset the fact that the plot follows an orphaned boy who lives with underground “monsters.” And October’s Guillermo Del Toro-produced The Book of Life—about a man who dies for his beloved—takes place in fantastical settings.

Why scare children, though? It’s about helping them deal with and understand their own fears. And that's not easy to do. "The really challenging concept [for authors] is to illustrate the emotions that might be negative," Stevenson says, "like anxiety, grief, and fear.”

Illustrating those emotions, Stevenson says, means getting the characters right. Lilly’s Squickerwonkers, for example, present duality between the good and the bad in every person—a duality that can help children question what’s right and what’s wrong. Her characters may be outcasts, but they’re not, as Lilly puts it, “malicious or malevolent,” just unaware of themselves. They may be menacing in appearance with their doll-like designs, but they’re also lively and warmly lit by illustrator Johnny Fraser-Allen, bringing to mind a carnival instead of a haunted house.

“What the Squickerwonkers are really dealing with and talking to children about is human nature, the not-so-pretty sides of human nature,” Lilly says. “Children are oblivious to their own vices, and that’s why they can hurt each other so badly. If children are not familiar with them, they’ll just be afraid of them and confused by them and ashamed of them.”

In The Boxtrolls, a character named Mr. Pickles starts out as a henchman of sorts for the antagonist, but doesn’t realize it, convincing himself he’s “good.” As the film progresses, he realizes he’s not—making him neither good nor bad. As Dan Harmon put it in his letter to a little girl who had gotten nightmares after watching Monster House, for which he had co-written the screenplay:

There should always be something inside a monster that helps you understand it, and makes you less scared of it, and able to make the monster go away. Not just a bunch of stuff that makes you more confused and scared.

But having a multi-layered character isn’t the only step to constructively tap into children’s fear. Building a creative world, according to Stevenson, is just as important. Adults may “like the idea of books as a safe place away from the real things,” she says, “But you can’t expect a child to never deal with fear if they’ve never encountered it.”

In other words, writing for children means emotionally engaging on their level. Sometimes, that takes creating a fantastical world that, however fearsome it may be, allows children to explore. There’s a weirdness that should be captured: The Book of Life uses the land of the dead as a setting, something inherently horrific for children to think about. (The film itself grasps this. In one scene, a child character listening to the story exclaims, “What kind of story is this? We’re just kids!”) To offset the horror, the film uses elaborate and colorful art direction.

Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, Stevenson says, effectively demonstrates this idea. The book’s art built a palatable world, an idea Sendak explained in 1964 while accepting the American Library Association’s Caldecott Medal presentation:

[It’s] an awful fact of childhood… The fact of [a child’s] vulnerability to fear, anger, hate, frustration—all the emotions that are an ordinary part of their lives and that they can only perceive as dangerous, ungovernable forces. To master these forces, children turn to fantasy: that imaginary world where disturbing emotional situations are solved to their satisfaction.

Scaring and disturbing children is essential—but it has to be done right. It’s not about scaring the crap out of them, it’s letting them explore a world that only horror can introduce, and opening up that genre to find out what is truly scary, what is creepy, and even what is downright funny to them about these stories.

“Writing a dark story, it’s not because I want to horrify children,” Lilly says. “I want it to be weird and strange and creepy and quirky. [The books] will lead to a discussion for parents to have with their kids, like ‘What can we learn from our vices and how can we handle them?’”