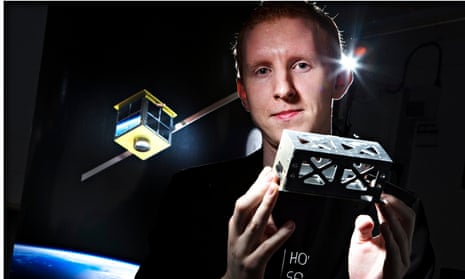

Most of the thousand or so operational satellites in orbit are multi-million-dollar machines that provide major industries with scientific research, global positioning or military espionage. Twenty-five-year-old Tom Walkinshaw, however, hopes to prove that satellites are not the preserve of leviathan space agencies, and that, for a comparatively small sum ($20,000), the workaday enthusiast can build and launch a fully functioning satellite of their own. One year old next January, his company PocketQube Shop provides the basic materials for doing this, most importantly the PocketQube structure itself - a tiny, 5cm³ casing made from aerospace-grade aluminium – which houses each satellite’s components.

“We want to remove as many barriers as we can for people who want to build satellites,” says Walkinshaw, and the PocketQube structure is the key to this endeavour. Invented in America, it is smaller than its predecessor the Cubesat, a 10cm³ design which was formerly the best hope for those seeking a budget satellite. Walkinshaw’s was the first company to recognise the PocketQube’s potential and begin manufacturing it, and it also supplies a number of other components, with a view to becoming a centralised hub catering to all satellite-builders’ needs. “We’re going to produce a PocketQube kit with a structure, radio and on-board computer,” pledges Walkinshaw, “and we just won a £63,000 from Scottish Enterprise to develop a combined powerboard and battery.”

Walkinshaw has managed all this from his home town of Glasgow, a surprising focal point for the future of the global space industry, but a town that he claims is becoming a “hotbed of satellite technology”. The firm has already shipped PocketQubes all over the world, and though most of the interest has come from universities, where they are used for student projects, the client base is nonetheless broad: one customer is an after-work club of American satellite engineers; another is a Taiwanese space agency.

The capabilities of the smartphone-sized structure are, according to Walkinshaw, “limited only by the imagination” – even in its tiniest form it can house the components that align, propel and power the satellite, and the slightly larger 5x5x10cm version can include additions such as star-tracking technology or cameras. Walkinshaw imagines hundreds of PocketQubes linking together in space and gathering a breadth of real-time data which bulky traditional satellites could never provide. The only real obstacle to this dream is getting them there in the first place.

“The launch situation for PocketQubes is probably the worst it will ever be,” he says, explaining that there is only one company worldwide currently allowing Pocketqubes to hitch rides on their rockets.

Walkinshaw’s answer to this is, perhaps, predictable. “We’d like to organise our own launches from Scotland,” he says; an ambition that will require requisitioning some serious hardware. “The first PocketQubes were launched from a converted ICBM called the SS Satan. A vehicle for nukes repurposed for education - it’s a nice story!”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion