In their words: how children are affected by gender issues

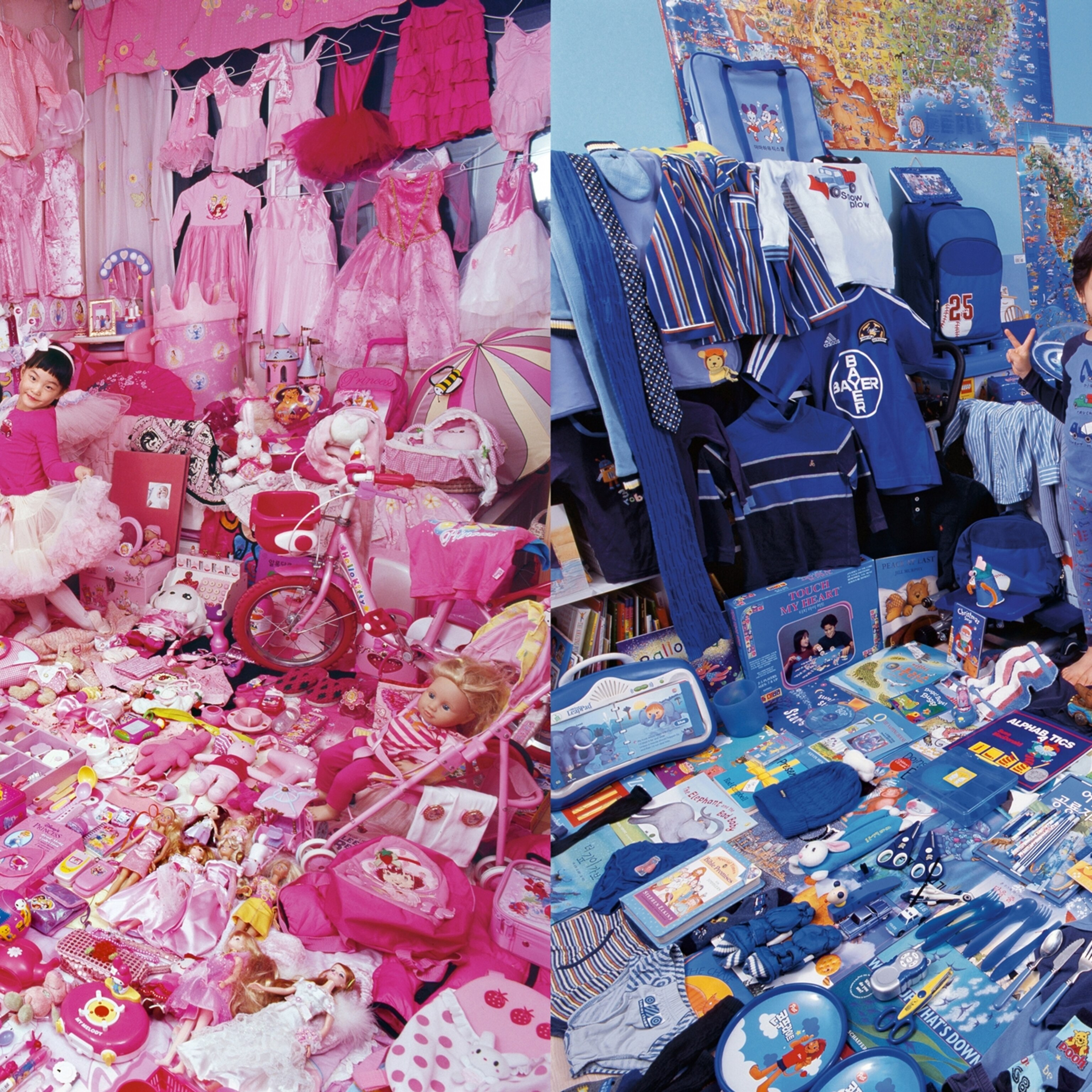

They're only 9 years old, but these girls and boys from around the world offer keen insight into how gender shapes destiny.

If you want candid answers about how gender shapes destiny, ask the world’s nine-year-olds.

At nine, a girl in Kenya already knows that her parents will marry her off for a dowry, to a man who may beat her. At nine, a boy in India already knows he’ll be pressured by male pals to sexually harass women in the street.

At nine, youngsters from China to Canada and Kenya to Brazil describe big dreams for future careers—but the boys don’t see their gender as an impediment, while the girls, all too frequently, do.

On the cusp of change, in that last anteroom of childhood before adolescence, nine-year-olds don’t think in terms of demographic statistics or global averages. But when they talk about their lives, it’s clear: Children at this age are unquestionably taking account of their own possibilities—and the limits gender places on them.

To get kids’ perspectives, National Geographic fanned out into 80 homes over four continents. From the slums of Rio de Janeiro to the high-rises of Beijing, we posed the same questions to a diverse cast of nine-year-olds. Being nine, they didn’t mince their words.

Many readily admitted that it can be hard—frustrating, confusing, lonely—to fit into the communities they call home and the roles they’re expected to play. Others are thriving as they break down gender barriers.

What’s the best thing about being a girl?

Avery Jackson swipes a rainbow-streaked wisp of hair from her eyes and considers the question. “Everything about being a girl is good!”

What’s the worst thing about being a girl?

“How boys always say, ‘That stuff isn’t girl stuff—it’s boy stuff.’ Like when I first did parkour,” an obstacle-course sport.

Avery spent the first four years of her life as a boy, and was miserable; she still smarts recalling how she lost her preschool friends because “their moms did not like me.” Living since 2012 as an openly transgender girl, the Kansas City native is now at ground zero in the evolving conversation about gender roles and rights.

The grown-ups talk about it—but kids like Avery want to have their say too. “Nine-year-olds can be impressively articulate and wise,” says Theresa Betancourt, associate professor of child health and human rights at Harvard University. They face increased peer pressure and responsibility, she says, but not the conformity and self-censorship that come with adolescence.

When asked the best-and-worst-things questions, Sunny Bhope—who speaks as his mother cooks rice over a charcoal fire, sending smoke through his small home near Mumbai, India—says the worst thing about being a boy is that he’s expected to join in “Eve-teasing,” his society’s euphemism for sexually harassing women in public.

For Yiqi Wang in Beijing, the best thing about being a girl is “we’re more calm and reliable than boys.” And for Juliana Meirelles Fleury in Rio, it’s that “we can go in the elevator first.”

How might your life be different if you were a girl instead of a boy (or a boy instead of a girl)?

Jerusalem’s Lev Hershberg says that if he were a girl, he “wouldn’t like computers.” Fellow Israeli Shimon Perel says if he were a girl, he could play with a jump rope.

If they were boys, Pooja Pawara from outside Mumbai would ride a scooter, while Yan Zhu from China’s Yaqueshui village would swim in a river that her grandmother insists is too cold for girls. Because she’s not a boy, Luandra Montovani isn’t allowed to play in her Rio favela’s streets, where she says the dangers include “violence and stray bullets.”

Eriah Big Crow, an Oglala Lakota who lives on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, says in a near whisper that there’s nothing that she can’t do, because boys and girls are “exactly the same.”

Eriah’s claim might sound too optimistic to Anju Malhotra, UNICEF’s principal adviser on gender and development. With respect to gender inequality, she says, “we’re not seeing an expiration date for it yet”—but there is progress.

For global citizens under age 10, recent decades have seen more gender equity in areas such as primary school education access, says UNICEF’s Claudia Cappa. But statisticians can count only “those who were able to survive,” she notes, and “sex-selective abortions of female fetuses” persist in some countries.

Past the age-10 mark, however, the closing gap is replaced by a wide gulf. “Things change completely in adolescence,” Cappa says, with “striking” gender gaps in access to secondary schools, for example, or exposure to early marriage and violence. “This is when you stop being a child,” she says. “You become a female or a male.”

What do you want to be when you grow up?

Lokamu Lopulmoe, a Turkana girl living in rural Kenya, says that when she grows up, her parents will “be given my dowry, and even if the man goes and beats me up eventually, my parents will have the dowry to console them.” Some 300 miles away, in a gated community in Nairobi, Chanelle Wangari Mwangi sits in her trophy-filled room and imagines a much different future: She wants to be a pro golfer and “help the needy.”

In Ottawa, Canada, William Kay confidently plans a future as “a banker or a computer, like, genius guy.” Beijing’s Yunshu Sang wants to be a police officer, “but most police are men,” she says, “so I can’t.” In Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania, budding journalist Hilde Lysiak rides around her neighborhood on a silver and pink bike, hunting for news—all the while suspecting that a boy reporter might “get more information from the police.”

What is something that makes you sad?

For Tomee War Bonnet, an Oglala Lakota, it’s “seeing people kill themselves.” What plants such thoughts in a nine-year-old’s head? Her reservation’s history of suicides, by kids as young as 12.

Mumbai’s Rania Singla feels sad when her little brother hits her. Lamia al Najjar, who lives in a makeshift home in the Gaza Strip, says, “I feel sadness when I see [how] our home is destroyed”—a result of fighting in the area in 2014.

What makes you most happy?

High on this list: family, God, food, and soccer. And friends. Other answers give a flavor of kids’ individual lives. One youngster loves powwows, another Easter eggs. For Amber Dubue in Ottawa, happiness is “room to run.” For Maria Eduarda Cardoso Raimundo in Rio, whose parents are separated, happiness is “Mom and Dad by my side, hugging me and giving me advice.”

Around age nine, Bede Sheppard says, children are “developing important feelings of empathy, fairness, and right from wrong.” As deputy director in the children’s rights division of Human Rights Watch, Sheppard has worked with child laborers, refugees, and other youngsters in dire circumstances. He says the most oppressed and disadvantaged can also be the most empathetic and selfless. Turkana herder Lopeyok Kagete dreams of giving away money and “slaughtering [livestock] for people to eat.” Though Sunny Bhope and his family live in a single concrete room, the Indian boy aspires to “provide rooms to the homeless.”

When nine-year-old girls and boys discuss themselves and each other, points of consensus emerge. Boys get in trouble more often than girls, both sides agree, and girls have to spend a lot of time on their hair. Such things are part of their reality—but much weightier matters are too.

If you could change something in your life or in the world, what would it be?

Rio’s Clara Fraga would make thieves “good, so that they wouldn’t steal.” Abby Haas would free her South Dakota reservation of the “bad guys.” Kieran Manuel Rosselli, of Ottawa, says he would “destroy terrorists.” The grim content of some answers, and the grave tones in which they’re delivered, give the impression of a miniature adult speaking, not a child. If she could, says China’s Fang Wang, the thing she would change is “what it’s like when I’m lonely.”

The aspiration mentioned most often, across lines of geography and gender, was summed up by Avery Jackson. If the world were hers to change, she said, there would be “no bullying. Because that’s just bad.”

This story was originally published January 2017.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico