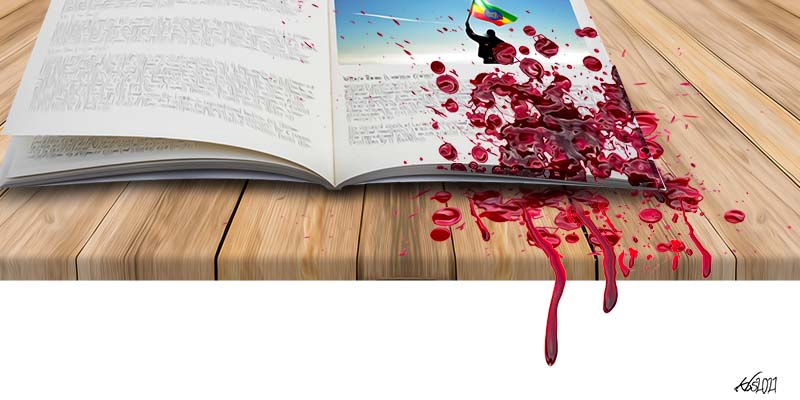

The joint United Nations (UN) and Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC) investigation is like a ham omelette: the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed. In this investigation, the UN only reluctantly became involved in demonstrating its efforts in investigating atrocity crimes, while the EHRC was committed to defending the government of Ethiopia – the architect of the war on Tigray.

Various reports on the investigation into atrocity crimes committed in Tigray are expected to be released in the coming weeks.

The report of the joint UN and EHRC investigation was released on 3 November 2021. The much-anticipated report by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the determination by the United States government on whether genocide against Tigrayans has been committed, are also expected to be released in the near future. These reports will be markedly different from the discredited report of the joint investigation.

The joint investigation’s report failed to establish facts because the Joint Investigation Team (JIT) had no access to the location it purported to cover and where most of the crimes are presumed to have been committed. Due to what the report calls “challenges and constraints”, the joint investigation was unable to access atrocity zones. It also underreported on, and failed to include, infamous atrocity zones in Tigray, including Axum, Abi Addi, Hagere Selam, Togoga, Irob, Adwa, Adrigrat, Hawzen, Gijet, and Maryam Dengelat as well as the Tigrayan bodies that washed up in Sudan on the Nile River. As in most cases, the worst atrocity zones in Tigray were located in active battlefields. Yet, the investigators were able to visit and interview witnesses in parts of Tigray that had been ethnically cleansed.

Victims side-lined

Moreover, the report downplayed the concerns of victims. The UN Basic Principles on Right to Remedy and Reparations, under Principle 8, define victims as:

[P]ersons who individually or collectively suffered harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights, through acts or omissions that constitute gross violations of international human rights law, or serious violations of international humanitarian law. Where appropriate, and in accordance with domestic law, the term “victim” also includes the immediate family or dependants of the direct victim and persons who have suffered harm in intervening to assist victims in distress or to prevent victimisation.

The final report did not include the findings of extensive interviews that the UN conducted with Tigrayan refugees from the second week of November 2020 through to the end of December 2020. These interviews were held in refugee camps in Sudan, with victims and witnesses of human rights violations of various kinds and to different degrees. According to some informants, the report was submitted to Michelle Bachelet, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, in January 2021. However, for unclear reasons, the findings of this investigation have not yet been made public, and there is no mention of it in the joint report. Informants say that few staff members of the Office of The High Commissioner for Human Rights in Addis Ababa raised questions regarding the integrity of the investigation carried out by their colleagues in Sudan.

The voices of victims and witnesses of atrocious crimes who gave their accounts in complete confidence in the UN have been deliberately disregarded. Instead, the UN issued the report authored jointly with the EHRC while concealing the report its office in Sudan had produced earlier. This amounts to subversion of investigations and victims’ right to truth and remedy – a violation of international law. Reports indicate that the government of Ethiopia curtailed the UN’s role in the investigation including by expelling one of the UN investigators.

Witnesses were reluctant to participate in an inquiry involving the EHRC. As one of the challenges, the report mentions the “perceptions of bias against the EHRC in some parts of Tigray where some potential interviewees declined to be interviewed by the JIT because of the presence of EHRC personnel”. This is a deliberate understatement.

Tigrayan victims and Tigray authorities rejected the joint investigation from the outset and declared their non-cooperation. In a recent report the Guardian asserts, “Especially damaging has been the growing perception among Tigrayans, about 6% of Ethiopia’s population, that the commission is partial towards the federal government and hostile to the TPLF.”

The voices of victims and witnesses of atrocious crimes who gave their accounts in complete confidence in the UN have been deliberately disregarded.

Victims are right to fear reprisals by Ethiopian, Eritrean and Amhara forces, and this fear silenced many and reinforced victims’ non-cooperation since the EHRC was involved. Conversely, perpetrators believe they can get away with their crimes when the EHRC is leading the investigation.

A principal at the core of the concept of justice is redressing the wrongs done to victims. The interests of victims should thus remain central to any investigation. In Tigray, women are the principal victims of the war, and a deliberate campaign of rape and sexual violence has been as typical as murder.

By excluding the voices of the majority of victims, the UN violated its cardinal principle of a victim-centred investigation. Justice entails that victims have the right to the truth and that those responsible for victimising people are held to account for their actions in a transparent fact-finding process and held liable for remedying the harm caused. The truth of what occurred should be established through the verification of facts and full public disclosure.

Bad start

The joint investigation started on the wrong footing. The basis on which the decision to constitute a joint investigation was made, the terms of reference, the selection of the investigators, and the agreement between the UN and the EHRC have never been made public, despite many requests. They remain shrouded in secrecy.

Some claim that the EHRC was involved in this investigation for the UN to gain access to Ethiopia. Others argue that such a joint venture would help build local and national capacity for investigation. It is heartless to think of building local capacity at the expense of victims of mass atrocity crimes (rape, killings, displacement and destruction of livelihoods). In effect, in this investigation, though committed to addressing atrocity crimes, the UN has been allowed to play second fiddle to personalities of a national system. The UN offered a façade of independence and impartiality to the investigation. The decision to conduct this joint investigation politicized a process that could and should have been de-politicized.

Some claim that the EHRC was involved in this investigation for the UN to gain access to Ethiopia.

Given that a general situation of war, chaos and a breakdown in law and order has been deliberately created in Tigray to systematically and systemically commit atrocities, destroy infrastructure and loot property, fears of reprisal are real. Consequently, the victims had little confidence in the joint investigation’s impartiality, capability and mandate to establish the truth, let alone identify perpetrators – particularly those holding the highest offices of command, control and communication.

Pleas unheeded

For these reasons, many Tigrayans denounced the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for involving the EHRC. The investigation was, from the start, designed to fail the Tigrayan victims. Tigrayans consistently called for the UN to establish an international commission of inquiry equipped to investigate crimes of such magnitude and gravity.

What is more, the report subverted the core aim of a standard investigation. Investigations and findings should be based on verifiable evidence collected from the ground without any involvement from the parties to the conflict and institutions accused of bias. The UN also failed to follow its guidelines and precedence of establishing independent and international commissions of inquiry or international fact-finding missions, as it did in Burundi, South Sudan, Gaza, Syria, Libya, Sudan (Darfur), Côte d’Ivoire, and Lebanon. These exemplary investigations were comprehensive and served as historical records of grave violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, offered the victims truth, and ensured the legal and political accountability of those responsible. In addition to holding criminals accountable, such investigations are supposed to help in restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and above all, guarantees of non-repetition of violations.

One asks why the UN thinks the atrocities committed in Tigray are less deserving.

False equivalence

All investigations need to include all alleged violations by any party. The prosecution also needs to include all responsible parties to ensure that no justice is victor’s justice. This is not only the right thing to do but also the most effective method of legitimizing the process, ensuring accountability, providing remedies, and fighting impunity. However, such a process should not apply bothsidesism as a method of investigation and attribution of culpability.

Pulling the wool over the eyes of the international community, the report created false equivalence to disguise the real perpetrators. There are more paragraphs about calls for the cessation of hostilities, reconciliation, and capacity building than accountability, attribution of culpability, and ending impunity. The report is crafted in a manner that covers up the ringleaders of the crimes, softens accountability, advances recommendations that permit impunity in the name of reconciliation, and establishes false equivalence among warring parties. One paragraph in the report, for example, states, “International mechanisms are complementary to and do not replace national mechanisms. In this regard, the JIT was told that national institutions such as the Office of the Federal Attorney General and military justice organs have initiated processes to hold perpetrators accountable, with some perpetrators already having been convicted and sentenced.” The report advances proposals on non-legal issues including political causes of the war, humanitarian consequences and capacity building of EHRC.

Pulling the wool over the eyes of the international community, the report created false equivalence to disguise the real perpetrators.

It is bizarre that the UN believes that the Ethiopian National Defence Force and the Attorney General of the Government of Ethiopia can ensure accountability. The Ethiopian National Defence Force is a principal party in the war, and the Attorney General remains the chief architect of massive profiling of Tigrayans living outside Tigray, rounding up Tigrayans and leading the campaign for their internment. Like the EHRC, the Attorney General has no prosecutorial independence to hold officials of the Ethiopian government accountable.

Furthermore, many Ethiopians see only the victimization of their own group and not what their side has done to others. Dialogue, reconciliation and peace cannot be achieved while every fact is disputed. This report adds to the fierce dispute around the facts. For this very reason, many will continue to reject the report – as they did the investigation.

Victims’ demand

Overwhelming segments of the Tigrayan society reject the joint report. In particular, Tigrayans demand that the UN conduct its investigations, revealing Tigrayans’ high expectations of the UN’s ability to establish the truth based on which justice can be served.

Given the recent leaked audio recording that reveals the conspiracy against Tigrayans by some of the leaders in the UN Ethiopia office, one is forced to ask why Tigrayans have such high hopes in the UN. Many are left with no option but to reject outright the poison fruit of the so-called joint investigation, much as the victims, their families, the survivors and the Tigrayan community at large have done. By disregarding repeated calls for an international commission of inquiry, the UN has missed an opportunity for an empathetic and purposeful connection with the actual victims of the war.

Many atrocity situations such as in Rwanda, Darfur, Syria, and Burundi have been visited by the highest level officials of the international community. The highest-level officials of the UN, AU, IGAD and the US and EU leadership should travel to Tigray and other war-torn areas of Ethiopia. Even if permission from the government of Ethiopia for such high-level visits would have been difficult to secure, such attempts by high-level officials to visit the region would have demonstrated at least personal compassion and solidarity with victims. Such visits would have been viewed as both a symbolic and tangible commitment of leaders to end the war and the siege, and address impunity.

In the interests of the victims – and to place them at the centre of UN’s human rights work – the UN should authorize a UN-mandated commission of inquiry to investigate the atrocity crimes committed in Tigray and in other parts of the country.