Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago

Even at times when discrimination was much more common, catalogs contained more neutral appeals than advertisements today.

When it comes to buying gifts for children, everything is color-coded: Rigid boundaries segregate brawny blue action figures from pretty pink princesses, and most assume that this is how it’s always been. But in fact, the princess role that’s ubiquitous in girls’ toys today was exceedingly rare prior to the 1990s—and the marketing of toys is more gendered now than even 50 years ago, when gender discrimination and sexism were the norm.

In my research on toy advertisements, I found that even when gendered marketing was most pronounced in the 20th century, roughly half of toys were still being advertised in a gender-neutral manner. This is a stark difference from what we see today, as businesses categorize toys in a way that more narrowly forces kids into boxes. For example, a recent study by sociologists Carol Auster and Claire Mansbach found that all toys sold on the Disney Store’s website were explicitly categorized as being “for boys” or “for girls”—there was no “for boys and girls” option, even though a handful of toys could be found on both lists.

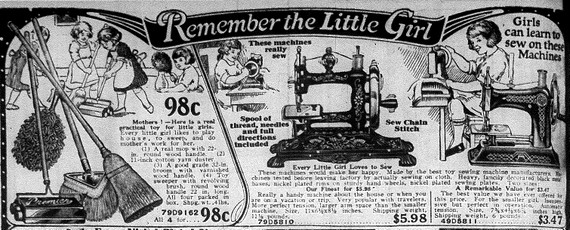

That is not to say that toys of the past weren’t deeply infused with gender stereotypes. Toys for girls from the 1920s to the 1960s focused heavily on domesticity and nurturing. For example, a 1925 Sears ad for a toy broom-and-mop set proclaimed: “Mothers! Here is a real practical toy for little girls. Every little girl likes to play house, to sweep, and to do mother’s work for her":

Such toys were clearly designed to prepare young girls to a life of homemaking, and domestic tasks were portrayed as innately enjoyable for women. Ads like this were still common, though less prevalent, into the 1960s—a budding housewife would have felt right at home with the toys to “delight the little homemaker” in the 1965 Sears Wishbook:

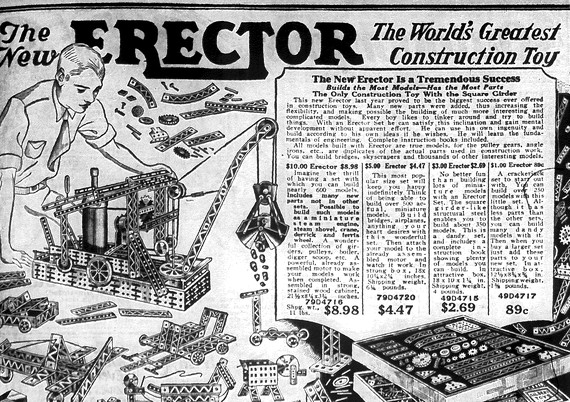

While girls’ toys focused on domesticity, toys for boys from the '20s through the '60s emphasized preparation for working in the industrial economy. For example, a 1925 Sears ad for an Erector Set stated, “Every boy likes to tinker around and try to build things. With an Erector Set he can satisfy this inclination and gain mental development without apparent effort. … He will learn the fundamentals of engineering”:

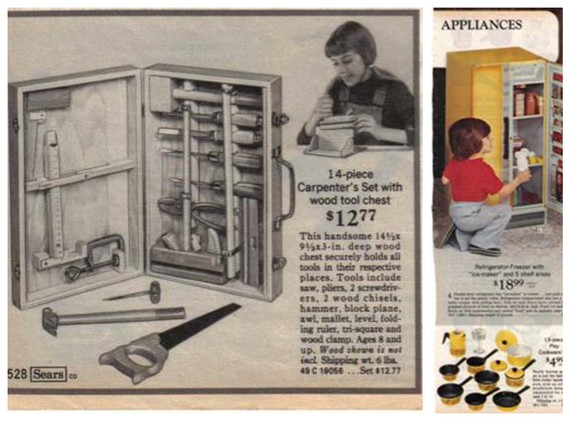

However, gender-coded toy advertisements like these declined markedly in the early 1970s. By then, there were many more women in the labor force and, after the Baby Boom, marriage and fertility rates had dropped. In the wake of those demographic shifts and at the height of feminism's second-wave, playing upon gender stereotypes to sell toys had become a risky strategy. In the Sears catalog ads from 1975, less than 2 percent of toys were explicitly marketed to either boys or girls. More importantly, there were many ads in the ‘70s that actively challenged gender stereotypes—boys were shown playing with domestic toys and girls were shown building and enacting stereotypically masculine roles such as doctor, carpenter, and scientist:

Although gender inequality in the adult world continued to diminish between the 1970s and 1990s, the de-gendering trend in toys was short-lived. In 1984, the deregulation of children’s television programming suddenly freed toy companies to create program-length advertisements for their products, and gender became an increasingly important differentiator of these shows and the toys advertised alongside them. During the 1980s, gender-neutral advertising receded, and by 1995, gendered toys made up roughly half of the Sears catalog’s offerings—the same proportion as during the interwar years.

However, late-century marketing relied less on explicit sexism and more on implicit gender cues, such as color, and new fantasy-based gender roles like the beautiful princess or the muscle-bound action hero. These roles were still built upon regressive gender stereotypes—they portrayed a powerful, skill-oriented masculinity and a passive, relational femininity—that were obscured with bright new packaging. In essence, the "little homemaker" of the 1950s had become the "little princess" we see today.

It doesn’t have to be this way. While gender is what’s traditionally used to sort target markets, the toy industry (which is largely run by men) could categorize its customers in a number of other ways—in terms of age and interest, for example. (This could arguably broaden the consumer base.) However, the reliance on gender categorization comes from the top: I found no evidence that the trends of the past 40 years are the result of consumer demand. That said, the late-20th-century increase in the percentage of Americans who believe in gender differences suggests that the public wasn’t exactly rejecting gendered toys, either.

While the second-wave feminist movement challenged the tenets of gender difference, the social policies to create a level playing field were never realized and a cultural backlash towards feminism began to gain momentum in the 1980s. In this context, the model outlined in Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus—which implied that women gravitated toward certain roles not because of oppression but because of some innate preference—took hold. This new tale of gender difference, which emphasizes freedom and choice, has been woven deeply into the fabric of contemporary childhood. The reformulated story does not fundamentally challenge gender stereotypes; it merely repackages them to make them more palatable in a “post-feminist” era. Girls can be anything—as long as it’s passive and beauty-focused.

Many who embrace the new status quo in toys claim that gender-neutrality would be synonymous with taking away choice, in essence forcing children to become androgynous automatons who can only play with boring tan objects. However, as the bright palette and diverse themes found among toys from the ‘70s demonstrates, decoupling them from gender actually widens the range of options available. It opens up the possibility that children can explore and develop their diverse interests and skills, unconstrained by the dictates of gender stereotypes. And ultimately, isn’t that what we want for them?