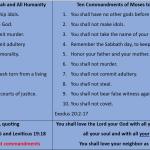

Several years ago, my colleague Susy Flory introduced me to Scott LeRette. Susy is a collaborative writer who had been hired to work with Scott to write a memoir about his family’s unusual story. Susy introduced us because Scott’s son Austin and his wife Teresa have osteogenesis imperfecta, the same brittle bone disorder I and my daughter have. Austin also has autism. And a love of really big hats and unique fashion combinations. And a sense of humor and a deep wisdom. Susy and Scott’s book, The Unbreakable Boy, is, as I said in my endorsement, about an entire family as much as it is about Austin. Their story is as wrenching and sweet and remarkable as it is unusual—not just because of Austin’s dual diagnoses, but because of how this family has coped with many other challenges, including a sometimes troubled marriage, addiction, and social isolation. Shortly after Susy introduced us, Scott asked me to write something for his award-winning blog “Austintistic” about pain and the bone disorder that I and half of his family share. Scott has allowed me to reprint that post here, with my hearty recommendation that you check out the Patheos Book Club page for The Unbreakable Boy to learn more about this remarkable family.

Our culture has a funny way of understanding pain. “Pain is gain,” we like to say. And it can be gain. The sore muscles and blistered feet from running miles every day are worth the thrill of crossing the finish line at your first marathon. The searing, tearing pain of childbirth leads to a warm bundle of impossibly tiny toes and rosebud lips and staggered breath that inspires love at first sight. Intellectually, we understand that the pain of a deep gash or scalding burn or broken bone is fundamentally good, because it tells us that something is wrong, that our vulnerable body needs help and protection.

If pain is gain, we think, then certainly there must be something good in all pain, right? So we offer up clichés to those in pain. We tell them that “everything happens for a reason” and “God won’t give you more than you can handle.” And then, being a culture of optimists, a people absolutely dedicated to the notion that through hard work and good decisions, you can fix anything, we expect people in pain to figure it out. When someone tells us they have chronic pain, we suggest diets and supplements and yoga and antidepressants and a good attitude.

But not all pain is gain. Pain is not always fixable. This is the truth. But it is not a hopeless truth.

Like Austin, I have osteogenesis imperfecta (OI)—a genetic collagen disorder that causes fragile bones and other connective tissue problems, such as scoliosis, muscle weakness, and skeletal deformities. Before my 11th birthday, I had about three dozen fractures, mostly of the legs, along with about a dozen surgeries to replace metal rods that helped stabilize and straighten my leg bones.

Like Austin, I have osteogenesis imperfecta (OI)—a genetic collagen disorder that causes fragile bones and other connective tissue problems, such as scoliosis, muscle weakness, and skeletal deformities. Before my 11th birthday, I had about three dozen fractures, mostly of the legs, along with about a dozen surgeries to replace metal rods that helped stabilize and straighten my leg bones.

For many of the past 30 years, I lived in a healthy denial of my condition. It was still obvious to me and even to casual observers that my body was compromised. My spine is crooked and one leg is longer than the other, so I walk with an awkward swaying limp. I haven’t ever been able to carry heavy loads, run, or walk long distances without pain. But from my teen years through my late 30s, I could go through most days without giving much thought to having OI. I could hike on the weekends with my husband, keep house and cook meals, walk to the drug store with a baby or two in a stroller—and rarely have to accommodate my bone disorder into my typical stay-at-home-mom routine.

That all changed when I was pregnant with my third baby, and tore some cartilage in my knee. I eventually had it surgically repaired, but in the years since, I have developed severe arthritis in both knees.

This pain is not gain. This pain means that I struggle to keep up with my family on outings, even with the support of a walking stick (I refuse to call it a “cane”!). This pain means that I hobble, hunched over, like someone twice my age when I take my first few steps out of bed in the morning. This pain doesn’t leave me alone even at night; changing position in bed can lead to shooting pain that wakes me up.

When it comes to remedies for arthritis pain, I have tried them all. I swim and do yoga. I have tried acupuncture, dietary changes and supplements, and homeopathic concoctions. I have had various types of injections. Most of these remedies have proved useless.

I have found two treatments that really help: Frequent, intense application of heat (via heating pads, very hot baths, and time spent outdoors in direct sunlight) and opioid medications. Neither remedy banishes my pain entirely, but together, they allow me to keep my house relatively clean and in order, prepare simple meals, and do things with my kids. (Knee replacements are a possibility long-term, but will be more complicated for me than for the usual arthritis patient. My orthopedist and I are agreed that, with three dependent kids still at home, I am not a good candidate for such drastic surgery right now.)

My pain is not gain. My pain is a cold, hard fact, the source of much frustration and even shame. I am, after all, dependent on medications that are the target of suspicion and fear, because of a prevalent pseudoscientific mindset that considers “natural” (unregulated and often untested) remedies as automatically safer and better than “unnatural” remedies produced and sold by Big Pharma, and because of a well-meaning but often misinformed media frenzy around prescription drug abuse. And my children, while of course they love me, don’t always understand my limitations. They roll their eyes when I say I’m heading upstairs to take yet another hot bath. “Mom!” they say. “I think you’re already clean enough!” They whine when I can’t do what they want me to do because I need to sit down and give my knees a break.

Our culture loves stories of people who triumph over pain and adversity. I do not triumph. I take lots of breaks. I complain. I wish I could do more than I can. I get angry when I’ve taken a pill and taken a hot bath and sat out in the sun and still one of my knees is screaming. I get angry because I know there is nothing else to do.

There is nothing else to do, that is, except the most important thing: Cope. I do not triumph, but I do cope. I cope pretty darn well. And I wonder if, in our culture that so loves stories of triumph and strives so mightily to fix whatever is wrong with us, glomming onto the latest technologies or natural remedies or self-help plans or diets or experts that populate the best-seller lists, we have forgotten the value of coping.

Coping is about continuing to put one foot in front of the other, admitting that some things are hard and frustrating and unfixable while giving thanks for other things that are good and inspiring and helpful. Coping is doing what we can while acknowledging all we can’t.

Theologian Stanley Hauerwas, in his book God, Medicine, and Suffering, quotes Nicholas Wolsterstorff, author of Lament for a Son—a memoir of losing his grown son in a mountain climbing accident and a meditation on parental grief. Wolsterstorff says, “I know now about helplessness—of what to do when there is nothing to do. I have learned coping. We live in a time and place where, over and over, when confronted with something unpleasant we pursue not coping but overcoming. Often we succeed. Most of humanity has not enjoyed and does not enjoy such luxury.”

Our culture doesn’t like helplessness. We are uncomfortable with pain and grief. So we pull out our clichés about everything happening for a reason and pain being gain. Mere weeks after the Boston marathon bombing, we pick up a People magazine with smiling amputees on the cover. We admire them for overcoming their trials with grit and determination, failing to acknowledge that they likely have days and weeks and years of hard coping ahead of them, of getting out of bed and going to work and caring for families under the weight of pain and grief and horrific memories.

Austin has OI as I do, and his dad Scott tells me that Austin lives with chronic pain as well. I have never met Austin. But if I could say one thing to him and to other kids living with challenges, such as OI or autism or other conditions affecting body and mind, I would say this:

You have had to deal with a lot of stuff in your young life, and you have borne that stuff with grace and strength. But I know—and I think you know too—that you are not a superhero. You are human. And stuff hurts. Sometimes it hurts a lot. When stuff hurts, whether it’s your body or your heart that is bruised, you don’t have to overcome the hurt. You don’t have to triumph over it. You don’t have to find a reason for it. You don’t have to learn a lesson from it (although once in a while, you will). You don’t always have to be brave and strong. You don’t have to inspire other people.

All you have to do is cope. Get up each and every day, decide what you really want and need to do, and then figure out how to do it. Figure out what eases the struggle a little bit, whether it’s finding meds or exercises or foods that really help, getting lost in a good book or a favorite video game, or spending time alone or time with other people. Admit when you’re hurt, exhausted, or frustrated, and ask for help—or just a listening ear. Push yourself to stretch beyond your limits, but only if you’re pushing in response to a deep yearning that’s inside yourself, not to impress others or fulfill their notion that you are some kind of symbol of how to overcome adversity. You are not a symbol. You are a person. And the people who really love and need you, they love and need you, the person you really are, with all of your gifts and limits and strengths and weaknesses.

It took me a long time to figure this out. I have spent far too much time comparing myself to other women my age, with their toned muscles and triathlon finishes and ability to come home from work to create a lovely homecooked meal and then go for a run and then take the dog for a walk, all without hurting. I have spent far too much time comparing myself to other mothers, who can ride bikes with their kids and keep up with them on strolls through town and carry them when they are exhausted. I am not happy about being a 46-year-old mom who has severe arthritis. But happy about it or not, that’s who I am. I am the best mom for my kids, the best wife for my husband, the best friend for my friends simply because I am theirs.

And I am coping. Not triumphing. Not overcoming. Just coping. Which is a lot, and really all any of us need to do.