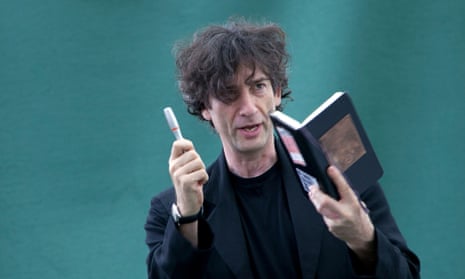

A feral child who was raised in libraries

Toby Litt: You’ve described yourself as a “feral child who was raised in libraries”. What age were you when you were first drawn into a library, and why do you think they hooked you?

Neil: I was probably three or four when I first started going to libraries. We moved up to Sussex when I was five, and I discovered the local library very, very quickly. But I wasn’t really hooked until I got to the point where I was old enough to persuade my parents to just take me to the library and leave me there, which would have probably been about seven or eight. And at that point it was like being given the keys to the kingdom.

Toby: Was it, was it a brand-new, 1960s, idealistic, “we’ll educate the masses” library, or was it a slightly down-at-the-heel one?

Neil: It was a very large, respectable Victorian house, of the kind that looked like it might have once been an upmarket doctor’s practice. The whole of the ground floor was books. In the back was the children’s library. You had a lovely, ancient wooden librarian ‘nest’ in the middle, where the librarians would huddle. Originally I was terrified of the librarians. I thought their job was to enforce fines – the equivalent of the Stephen King library police, you know?

But there was a point, I was probably about eight years old, when I discovered this series of books: the Alfred Hitchcock Presents ... Alfred Hitchcock’s Three Investigators, and I couldn’t work out how to find more of them. They didn’t quite seem to have Alfred Hitchcock as an author. They were Alfred Hitchcock’s Three Investigators, but he didn’t appear to be writing them. And I had to man up and talk to the librarian.

Toby: Approach the nest …

Neil: I did. The librarian – he was a very tall gentleman with a pretty dark beard – went off and figured it out. They managed to order more of these Three Investigators books for me, which made me ridiculously happy. I discovered that librarians were not scary people, which got incredibly important, because as a kid, I was obsessed with Gilbert and Sullivan. There were Gilbert and Sullivan plays that I had never read, and that you couldn’t find, and I discovered the interlibrary loan, which means that if your library doesn’t have the book, they will find it for you. And that was power!

A shelf with unread books

Toby: Isn’t the future of libraries dependent on not having gatekeepers who are scary, on libraries not looking ancient, and not being about distant, old knowledge?

Neil: I’ve probably been in about 6-700 libraries over the years, some of them that I researched in, some of them I took my children to; a lot of them I’ve visited for events, for launches, for opening graphic novel sections. I’ve seen so many wonderful libraries. One of my favourites is in Salt Lake City, in Utah, where they had giant, six-foot-high beanbag things on the kids’ floor, where you could collapse and disappear with your book and not come out for the day. And although those places would have been my idea of the Elysian fields, had someone described them to me as a child, really all I needed at that point in time was a shelf with books on it that I hadn’t read. And a relatively comfy chair. Actually, I didn’t care about the comfy chair. I look around at some of the wonderful libraries I’ve been to, and you know, they’re all glorious. And they have internet, and they have librarians who are delights, and they have “no-shushing” signs. But I think that what is most interesting to remember, always, is the platonic concept of a library. And the platonic concept of a library can be a caravan with some books in it.

Toby: Or library vans, you know, which still go around in Lambeth where I live, or did until a couple of years ago. But if you were a child now, what do you think would draw you in? A lot of the attraction of a library when I was growing up was based on lack. The library had stuff that wasn’t elsewhere. In your case, Gilbert and Sullivan; in my case, science fiction. If you imagine yourself as a kid now, why not get that stuff on your phone? Why do you need the building?

Neil: I think, firstly, nobody is curating the information for you. Nobody is giving you a safe space. I used to love libraries at school. Because school libraries had an enforced quiet policy, which meant they tended to be bully-free zones. They were places where you could do your homework, you could do stuff, whether it was reading books, or getting on with things that you wanted to get on with, and know that you were safe there. And people responded to your enthusiasms. If you like a certain writer, or a certain genre, librarians love that. They love pointing you at things that you’ll also like. And that gets magical. If you like RA Lafferty, you’ll like Ursula Le Guin, you’ll like Tolkien. And there’s web access. I’ve talked to a lot of librarians, and one of the things that they do is help people who do not have web access. Most job applications, and a lot of information on benefits and things like that, are out on the web. We act as if a smartphone and internet access are now handed out at birth. But it’s simply not true. A lot of people don’t have web access.

Toby: So the question is: if libraries are so great, why aren’t they a roaring success like the Tate galleries, with hundreds of people through the door. Surely they must be doing something wrong?

Success demands investment

Neil: Which libraries are we talking about? The new Birmingham library has been getting numbers through its doors that are very similar to the Tate gallery. They invested in a huge, glorious library. It’s a beautiful, beautiful space. And they did it just before the cuts came in … On the other hand, your question is a bit like asking: “Why is it that a local art museum, where they’ve cut the opening hours to three on a Monday afternoon and three on a Thursday, and half of the paintings are now stored around the back, isn’t a success on Tate gallery levels?” Maybe people need a little bit more. Look at Australia, where libraries are an enormous success, because nobody seems to have thought it necessary to cut the budgets. One of my favourite libraries in the world is in Melbourne, which has a grand piano! And when I went and did this fantastic reading, and my wife made music, and people were hanging around, there were about 1,500 people there. Wonderful people, wonderful space. The kind of space that makes you feel welcome.

Toby: But do you think that if a library is going to be around in 20 years’ time, there are things that need to be changed? Is there a point at which a library stops being a library and becomes a sort of civic centre, or something like that?

A safe space for reading

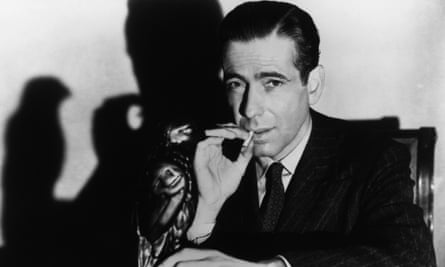

Neil: I think the most important thing is a space that’s safe, and safe in all sorts of ways. Safe to work, safe to think. And [a space that has] librarians, because the librarians are the people who are curating the thing. I would obviously always put a vote up for books around, because there’s nothing quite like the glorious serendipity of finding a book you didn’t know you wanted to read. Anybody online can find a book they know they want to read, but it’s so much harder to find a book you didn’t know you want to read. To just pick it up because the cover looks interesting. Pick it up because it’s sitting next to the book that you meant to pick up. Pick it up because it’s sitting there on the returned book stack, above, below the book that you were putting down. I would always have books around. Because there are studies now that seem to indicate that we absorb information differently if we’re taking it from a static page than if we’re taking it from a screen, which is fascinating. But if you told me that all you’d have is a comfortable room that was a safe space, with a person in it maintaining it, I could believe in that. You’d go over and you’d say, “I’ve heard of a film that was made back in the 20th century, and it’s something to do with a falcon, a black falcon, I think it was Maltese or something.” And they’d go, “Oh yes! Well, there’s a book, there’s a film, what would you like?” And you’d say, “Well, I’d like both.” And they’d press a little button, or wave their hands around, and hand you a unit, on which you would be experiencing both the classic film and the book. I can imagine that happening.

Toby: What do you think about library closures? Some will plead financial prerogatives?

Neil: I think it’s short-sighted. For me, closing libraries is the equivalent of eating your seed corn to save a little money. They recently did a survey that showed that among poor white boys in England, 45% have reading difficulties and cannot read for pleasure. Which is a monstrous statistic, especially when you start thinking about it as a statistic that measures not just literacy but also as a measure of imagination and empathy, because a book is a little empathy machine. It puts you inside somebody else’s head. You see out of the world through somebody else’s eyes. It’s very hard to hate people of a certain kind when you’ve just read a book by one of those people. So in that context, as far as I’m concerned, closing libraries is endangering the future. You know, at least with the libraries there, you’re in with a chance.

☻ This is an edited extract from an interview in Create, which will be published by the Arts Council on 18 November

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion