Reviewing a recap of five decades of the Booker prize feels like the definition of fiddling while Rome burns. However, if you have a fiddle and the raging conflagration – the colour of a madman’s hair, spreading as furiously and unstoppably as a Brexiter’s lie – is beyond the control of mere humans … well, what is there left to do?

So, let us shove the chinrest betwixt our collarbone and trembling jaw, wrap our hands, palsied with despair though they be, round the pegboard and enjoy Barneys, Books and Bust Ups: 50 Years of the Booker Prize – Air on an alliterative B string.

What larks they have all had since Tom Maschler looked at the Prix Goncourt, wondered why the French got to have all the fun (and sales uplifts) and persuaded Jock Campbell at the sugar trader Booker McConnell to sponsor a UK-based equivalent. Campbell had been instrumental in the company purchasing the literary copyrights of Ian Fleming, Agatha Christie, Dennis Wheatley and the like.

The first winner was PH Newby for Something to Answer For. Interviewed afterwards, he said: “I don’t regard myself as a very good writer, because I know too much about the literature of the past to delude myself in that way.” He and his family knew he had won before the ceremony, but his daughter declined to take part in the betting that was going on in the loos beforehand.

Sure, you can do it that way. But why not be an obnoxious pig instead? In 1980, Anthony Burgess sulked in his hotel room instead of coming to the do because the judges wouldn’t tell him whether he had beaten his rival William Golding to the prize (mainly, it turned out, because he had not). In the aftermath, Burgess intoned that he had been shortlisted twice for the Nobel prize: “Which is of some significance. This is a rather small, parochial prize for small, parochial novels.”

I am reminded that the violin is an instrument that sports something called an F-hole.

The clip of Burgess, by the way, netted two points in Booker bingo: for use of the word “parochial” and for the sighting of a literary lion skinning himself in public to show the quivering prawn-child within. (A full house is earned, of course, when Julian Barnes’s description of the award as “Booker bingo” is cited, which happened about five minutes into Kirsty Wark’s voiceover. The winner gets to drink a pint of the berk cocktail – red wine, lard, vitriol and cigarette ash – from the Kingsley Amis toby jug and goes on a three-day bender with John Banville.)

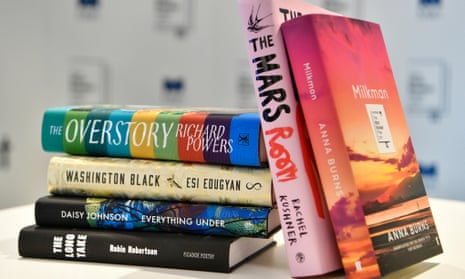

The programme tracked the prize’s progression (or regression) from small, intimate award to gape-mawed monster. Over the years, it has become capable of turning unknown authors into millionaires overnight and is famous primarily not for its contribution to English letters, but for the wrangling between judges and the controversies that are no such thing, except to the three people who think so.

The programme kept trying to slide past the millionaire issue with talk of the Booker’s fine work discovering new and diverse voices (footage of Salman Rushdie and Ben Okri doing a lot of work here) but somehow, like heads swivelling towards an accident on the motorway, it couldn’t help but keep returning to the subject. If you win the Booker, your sales will rocket. Small publishers can become players in a heartbeat – when Yann Martel won for Life of Pi, Canongate’s turnover increased by 50% that year and hasn’t stumbled since. Lives are transformed. It’s like winning with a lottery ticket you have earned instead of bought. What could be sweeter?

It didn’t dwell much on any broader questions about the idea of identifying a “good” or “best” book, what happens to readers and writers when a market can be skewed by such a big beast, or on what was claimed to be the Booker’s central concern – to answer the question of why The Novel still matters – but it was a hilarious (sometimes wittingly, sometimes not) jaunt through a little bit of very English history. While the future burns! Play on!

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion