ANN ELLISON IS SLEEPING WHEN HER husband quietly wakes the kids, gets them dressed, and drives them to church. When they return, she still hasn’t awakened. Her husband, James, gets panicky when Ann sleeps too long. Once, afraid Ann wouldn’t wake up, he shook her until her eyes opened. Sometimes, in the middle of the night, he leans over to shake her when she begins to scream during one of her nightmares. Ann regularly dreams that she is being buried alive, or that one of her children is dying. Sometimes she dreams that her children are alive, but when they look at her photograph, they can’t remember who she is. On this morning, when James comes in to wake her. Ann looks shriveled. Drops of sweat slide down her neck and soak the pillow. Her weight is down to eighty-eight pounds and her breathing is shallow. When she coughs, the sound is dry and empty, like the noise of one small rock scraping another.

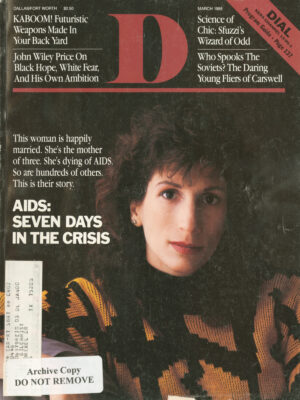

Ann, twenty-nine, is dying of AIDS.Ann (not her real name, though she did pose for photographs) believes she contracted the AIDS virus several years ago when she was dating a lawyer who did not tell her until the end of the relationship that he had had homosexual experiences. In December 1986, she came down with an AIDS-related pneumonia. She is the mother of three young children, all of whom are just beginning to sense that something very wrong is happening. Even her two-year-old son will get up on the other side of the bed and stare solemnly into her face when she coughs and spits mucus into a cup. When she awakens, Ann Ellison smiles weakly at her children; with her husband, she puts on her most cheerful, stoic manner. She knows it is the only defense she has against the most harrowing plague of our lifetime, a medical mystery for which there is no cure. Since 1981, AIDS has afflicted a reported 935 Dallas residents, only 370 of whom are still living. The epidemic here is just beginning: in 1986 Dallas had the largest percentage increase in AIDS cases of any metropolitan area in the nation (287 new cases, a 73 percent increase over the previous year). In 1987. the number of AIDS cases rose 74 percent with 397 new cases. For 1988, the Dallas County Health Department predicts 680 more cases. By 1991, according to the most conservative estimate, AIDS will have blighted the lives of some 6,000 people in Dallas County. Nationwide, by 1991, at least 270,000 will have been stricken (although other studies claim the number will approach 400,000), and at least 179,000 will die. The disease that we once could say was someone else’s problem-gays, IV drug users -is suddenly our disease,

This story is a portrait of one week in the AIDS crisis he re. From December 6 through December 12, 1987, D interviewed dozens of those fighting this killer virus-victims, doc-ton, activists, volunteers. Though for some people, AIDS is merely a subject upon which to argue speculative moral questions, and. though for many more, it is still “a gay thing,” the disease is quietly making its way into the mainstream, terrorizing those who never thought they would have to deal with it, forcing thousands of others to cope with the desolation of young lives cut down too soon. Some still find reassurance in the fact that 94 percert of the AIDS cases in Dallas involve homosexuals-though statistics tell us the heterosexual cases will increase tenfold in the next three years. But many more are beginning to realize that a pestilence tearing at any corner of the communal fabric tears at the community as a whole.

The week, chosen arbitrarily, was relentlessly tragic, darkened by hopelessness and rage, illuminated by courage and endurance. Some of the AIDS victims you will meet in this story have been abandoned like lepers; some have deliberately hidden themselves away. Some wait to die; others cling adamantly to any hope of life. Some cannot cope with the uncertainty, but others experience a new sense of purpose and discover the fragile human bond that links those who learn to live and die together. This is the face of AIDS in Dallas.

Sunday Morning, December 6- The Church Service

While Ann Ellison sleeps, Don Flaigg, the former assistant director of nursing at Methodist Hospital, is dressing to attend services at the Episcopal Church of Saint Thomas the Apostle, just west of Highland Park. Though he tries to eat six meals a day, Flaigg, forty, looks alarmingly thin. His legs quickly grow numb when he stands for too long. Knowing he only has the strength to be out a few hours a day, Flaigg plans his schedule carefully, and each Sunday he always plans for church. Since February 1987, when he learned he had contracted AIDS, he has come here to Saint Thomas, which has the most active ministry to AIDS patients in the city. The church had no acknowledged homosexual members until 1984, when a man walked into the priest’s office and said he was dying of AIDS. The priest, the Rev. Ted Karpf, befriended him and asked him to come to Sunday services. When the other 180 members heard an AIDS patient was in their midst, most of them left. Within a year, only fifty people were attending Mass. Karpf, married with two children, persisted in what he felt was his duty to serve those who were not cared for, “While you may be scared,” he would say in his powerful, deep voice, “you must know you are never alone.” Now the church is back to 200 members, 40 percent of whom are gay.

On this, the second Sunday of Advent, a time of celebration for Christians, the tenor soloist at the little church sings “Comfort Ye My People,” an aria from Handel’s Messiah that speaks of a coming promise of joy. But the song seems to hold a different meaning for the solemn congregation at Saint Thomas. Over the weekend, another of their members, Jeff Lewis, has died of AIDS. When Flaigg, sitting by himself on the third row, reads about the death in the bulletin, his face turns ashen. “He was just having a party last week,” Flaigg says. In the church that morn-ing are seven other people dying from AIDS. They hardly move as Karpf announces that Lewis’s funeral will be that afternoon. The last words Jeff said to his lover, Karpf tells the group, were, “just remember that I love you.”

Like many homosexuals, Flaigg moved to Dallas in the mid-Seventies just as the Oak Lawn area was blooming with gay life. Along Cedar Springs came the first gay bars and stores that catered to gay clientele. In the early Eighties, the gay community began to hear of something called “gay cancer,” a disease that affected homosexuals. But for most of these men, who at last had the opportunity to publicly acknowledge their sexuality after years of hiding it, the idea that a new plague was jeopardizing their lifestyle just seemed impossible.

Nevertheless, the truth was seeping out: something called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, resistant to anything science could throw at it, was being transmitted through semen, usually through anal sex; or through an exchange of blood that occurs when the needle of an infected drug user is used by someone else; or through a blood transfusion from another infected person. But even after the National Gay Leadership Conference, conducting its 1982 annual meeting in Dallas, announced that AIDS was the dominant issue for gays-or when Joe Fillpot, a popular gay bar owner, died from AIDS in 1982, the first well-known figure among Dallas homosexuals to succumb to the disease-there were only a few tremors of concern.

Flaigg himself didn’t even see an AIDS patient at Methodist Hospital until early 1985. “I walked in and looked at him,” he remembers, “He had lost a lot of weight, and he had these vacant, dark eyes. No one came to see him. He just stared at the ceiling. All the nurses and staff members were afraid to go into his room.”

Two years later, Flaigg would find himself stricken with AIDS. He had to quit his job, and he went to Karpf to plan out his funeral: Flaigg asked Karpf to play music “that will make people’s ears stand back.” Though old friends dropped by for occasional visits, he became more and more isolated. He did meet a new friend, another AIDS victim: each morning they would find an odd sense of reassurance simply talking on the phone about their latest pains. “But I don’t think about dying,” Flaigg says. “I only accept the fact that my life is being shortened.”

When the Sunday service ends, Flaigg hugs Karpf at the church entrance. Slowly, gingerly, he heads for his car. He is aware of his fate and accepts it with grace. “He was so sick a few months ago,” says Karpf, “that he should have died. But he’s a quiet fighter. He’s one of the few winning stories I’ve still got left to talk about.”

Karpf, however, has little time to talk. The rector hurries into his office so he can prepare his eulogy for Jeff Lewis’s funeral that afternoon. For Karpf, it will be the forty-seventh funeral in three years for someone who has died of AIDS; he has buried more people than he has married or baptized. Now. alone in his office, surrounded by stacks of books that try to iathom the power and goodness of God, Karpf writes, “We are feeling rage, rage at what this has done to him and so many others. But this passing cannot be the last word on his life. He did not die because of God’s will. He died because of a tragedy.”

Sunday Evening-The Goodbye Party

The ironies continue. Mike Richards, the most important leader in Dallas’s fight against AIDS, has come to a party to say goodbye to his friends. Since 1982, he has run what is now the AIDS Resource Center on Cedar Springs, a small, shabby storefront that is, astonishingly, the main operation in the city devoted to providing services for those stricken with AIDS and unable to care for themselves. It was Richards who helped create a volunteer network to assist AIDS victims. He started a food bank and financial assistance programs for persons with AIDS. He lobbied local politicians for money to combat the disease, he traveled at his own expense to AIDS conferences to learn more, and he started an AIDS hotline to educate those who knew nothing. At the dawn of the crisis, in 1982, the Dallas Gay Alliance gave him one room of their offices, where he would sit throughout the day and answer the phone, counseling those who had come down with this strange disease. He worked for two years, seven days a week, without pay. Now, all the offices of the Dallas Gay Alliance are devoted to AIDS, and now, Mike Richards is dying of it.

Richards, forty-one, is moving to Hawaii to spend the last days of his life. “If I stay here,” he says, “I will keep working on AIDS, getting angry all over again that nothing will be done. It might be dramatic to die at my desk, but I figure maybe it’s time to step back.” Though he has no friends in Hawaii, his parents, a small-town West Texas couple in their eighties, have decided to move with him.

Tonight, in the back room at the Cadillac Bar, the leaders of Dallas’s gay movement have gathered to wish Richards farewell. In some ways, for them, this is the cruelest blow. The first prominent local AIDS leader, Howie Daire, who created the Oak Lawn Counseling Center to address the needs of the gay community, died of AIDS in 1986. Now comes Richards, who didn’t learn he was suffering from the disease until last September (he says he began practicing safe sex in 1982). Two days after the diagnosis, he walked into a reception for the AIDS Action Council national meeting that was taking place in Dallas and acted as if nothing was wrong. Richards had been a forerunner in the fight for so long, he could not stand the thought of being the victim.

“We’re saying goodbye to an era,” says William Way bourn, president of the Dallas Gay Alliance, as he looks at Richards. Richards is still pale, the aftereffects from a recent bout of pneumonia; his spleen and liver are enlarged; he has a gum infection. The dreaded night sweats have returned and he has little energy. “Something could happen tomorrow,” Richards says. “That’s the way this works.”

At the party, several people recall some of Richards’s efforts to increase awareness of AIDS-from a rather embarrassing fundraiser in which two drag queens were featured in a mud wrestling competition, to his successful attempt to get former Mayor Starke Taylor to sign a Safe Sex Week proclamation for Dallas. Richards, of course, knows that one of his biggest campaigns a few years ago was persuading some of these very men here at the party that an AIDS crisis existed. Repeatedly he told them that they were all susceptible and that the disease, left unchecked, could destroy a generation of gay men. Today, he needs to say no more.

Monday Morning, December 7- The Hotline

The post-weekend “guilt calls” are coming into the AIDS hotline. Andy Abernathy, a twenty-five -year-old computer graphic artist who volunteers once a week at the AIDS Resource Center, listens sympathetically as a woman calls about a man she slept with over the pas weekend. In a moment of passion, she says, she got carried away, and she’s certain now that she has AIDS. Why? asks Andy. It just feels that way, she replies. She wants to get he HIV (AIDS antibodies) test immediately Andy tries to reassure her that there is no reason for panic, but if she wants to take the test, he suggests waiting two months; it can take that long for the AIDS antibodies to appear.

The phone lights are blinking. Another woman whose voice Abernathy recognizes calls to ask about AIDS. “She’s been tested a dozen times,” whispers Abernathy, “but whenever she reads another AIDS article in the newspaper, she gets paranoid and calls here and go:s to get tested again.” A call comes in from a man who in very measured tones asks at out symptoms of AIDS. Abernathy recognizes this kind of call as well. “They act totally nonchalant,” he says, ’”but if you keep them on the phone, toward the end they’ll admit they are scared to death.”

A mother phones to ask about a cut on her daughter’s head. It hasn’t yet healed. Could it be AIDS? Virtually impossible, says Aber-nathy. A man calls and says he hasn’t been able to shake a cold. Could it be AIDS?

“How long have you had the cold?” asks Abernathy.

“Twenty-four hours,” the man says. Abernathy tells him to stop worrying.

There are the usual assortment of calls about casual contact. Can you get AIDS by touching an AIDS patient? Can you get it by swimming in the same pool as a person with AIDS? Letting him wash your hair? No, says Abernathy, over and over. If someone who suffers from AIDS sneezes, coughs, or spits on you, even then it is highly improbable you will get AIDS, he tells the caller.

“One of the worst things about this crisis is that people are afraid to talk about it,” Abernathy says, “and that just makes the ignorance worse.”

But even more discouraging is the kind of phone call that he has to take later in the day: a worried young voice says he’s just learned he’s tested positive for AIDS.

“I’m scared,” the man says.

Abernathy sighs. “I know you are,” he says softly.

Monday Afternoon-The Clinic

At the Parkland Memorial Hospital AIDS clinic, the clinic’s director, Dr. Daniel Barbara, thirty-four, moves from one examination room to another, haplessly trying to keep up, With 469 patients now regularly coming to the clinic, there is never enough time. The hospital has promised Barbara an assistant physician in January, but that will only put a dent in the backlog. Barbara shrugs, studies the chart of a young man who is in to see him for the first time, and begins to find out what’s wrong.

“You’re cold, huh?” he asks, toying with the ear plugs of his stethoscope. He can tell the young man, who’s wearing cowboy boots, jeans, and a Western shirt, is nervous. His HIV test came back negative, but many of his symptoms-from weight loss to fevers to anemia-point to the disease. Barbara gives him a reassuring smile.

There are hundreds in this condition who come to see Barbara-knowing something inside them is wrong and fearing the worst. Barbara tells the young man that he needs to take the HIV test again to see if, this time, it will come up positive. Other than that, they must wait.

Barbara heads into another examining room where a gay couple sits silently. One has contracted AIDS and the other is showing signs of it. In another room is a patient with extreme dementia (the AIDS virus sometimes attacks the brain) who barely seems to understand any of Barbara’s questions. His next patient is suffering from pneumocystis, the unusual form of pneumonia found in AIDS victims.

Many of the patients ask Barbara if they have moved up on the waiting list to receive AZT, the only treatment known to prolong the life of AIDS victims. Because of the expense-AZT costs between $8,000 and $10,000 a year per patient-Parkland has limited use of the powerful drug, which must be taken every four hours around the clock and can cause severe bone marrow damage and anemia. Only ninety-three people are given the drug at a time; there is a waiting list of another thirty-two.

The AIDS crunch has indeed hit Parkland, the county’s public hospital. It costs almost $900 a day for an AIDS patient to be hospitalized at Parkland (up to fifteen are hospitalized at a time), and since most AIDS patients cannot qualify for insurance and are unable to contribute much to the cost of their stay, Parkland absorbs most of it, recovering only 17 percent of those costs from insurance and Medicaid. Parkland spent $3 million for AIDS care in 1987, but Ron Anderson, chief of Parkland, says the costs for 1988 will nearly triple because of the increased number of cases, soaring to $9 million-money that Anderson says Parkland does not have.

One of the big political questions of the late Eighties is: who will pay for AIDS? Certainly not those who have the disease. Wandering through the AIDS clinic waiting room is Mac McMurtry, the hospital’s social worker for AIDS who spends the bulk of his time working with patients on their finances. “Most of these guys,” McMurtry says, “are from middle-class incomes. They’ve made it in their own ways and they’re successful. And then suddenly they can’t work and they can’t get insurance and they start getting maybe $330 a month in Social Security disability income-and that won’t even pay for their car.”

Late Monday Afternoon-The Well ness Session

In a dark little room at the Oak Lawn Counseling Center, where many victims of AIDS go for psychological counseling, a group of men and women sit on the carpet, striving to outwit the disease. “Healing can be on any level,” says Mary Grigsby, a staff therapist, “even through something as simple as a positive attitude. If someone with AIDS spends his time worrying that his immune system is about to break down and that he’s going to get sick, then his mind can actually pull the body toward that sickness.” As they shut their eyes, a young man with AIDS. Doug Byrd, leads the group in a meditation. “Imagine yourself,” he says, “in a forest, and light conies streaming through the trees.” Later, they get in a circle and massage one another’s hands. Then they tell three things for which they’d like to be forgiven. At the meeting’s end, everyone in the room gets a hug.

Can right thinking triumph where medicine is helpless? To an outsider the efforts might seem futile, but not to the OLCC. “What’s wrong,” asks Grigsby, “with trying to focus on the idea of loving oneself?” Or, as John Etheridge, another AIDS sufferer, puts it, “It will be sad to die of AIDS. But, God, how much worse would it be to die of skepticism?’

Monday Evening-The Banquet

They are known as “buddies,” They are the volunteers who care for victims of AIDS, and tonight they get to do something rare: celebrate. He re at their annual banquet at the Regent Hotel, attended by nearly 200 “Buddies,” awards are passed out to the top volunteers. People applaud and tell funny stories. The know that tomorrow, their life with AIDS begins again.

The Buddy project, run through the Oak Lawn Counseing Center, offers a seventeen-hour trainirg course (which includes a lesson in funeral planning) in order to prepare a volunteer to help support a person with AIDS.’ The volunteers, who four years ago consisted entirely of gay men, now come from everywhere: there are teenagers and senior citizens, dental hygienists, housewives, bankers, blue-collar workers, all responding to the plague with compassion instead of fear. They help a person with AIDS do his shopping or prepare meals. As the victim gets weaker, they’ll bathe him and slay with him at the hospital.

“We must Jo the things we never expected to do,” says the banquet’s speaker, Paul Kuwata, executive director of the National AIDS Network, a clearinghouse and lobbying agency in Washington, D.C. Kuwata says he is “frightened for Dallas.” He knows that beyond the $730,000 that the county will spend on AIDS testing and education in 1988 ($600,000 of that coming from federal funds), there is no money for AIDS prevention other than that raised through private donations and grants. Texas has made a pathetic response to the crisis: though it has the fourth highest number of AIDS cases among stales, it ranks forty-seventh in spending for AIDS. Two years ago the private, nonprofit AIDS support organizations staved off near collapse when the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provided a $1.5 million grant, but even that money is rapidly being depleted. The care of AIDS patients in Dallas largely depends on the volunteers.

“We must learn not to cry,” Kuwata says to the Buddy volunteers, his voice choked with emotion, “because if we cried every time someone we loved died, then we’d never get anything done.”

Tuesday Morning, December 8- The Baby

Lindsey, wearing little red earrings and bows in her hair, is sitting on her grandmother’s lap, kicking her legs, staring curiously across a waiting room at other babies who come to Children’s Medical Center. It is as close as she ever gets to them. Lindsey, ten months old, has already lived four months longer than doctors expected. Diagnosed with AIDS soon after birth-her mother, a prostitute and drug addict, also has AIDS-Lindsey lives in Oak Cliff with her grandmother, Gloria (not her real name). Frightened that the neighbors will run her out of the neighborhood if they find out about Lindsey’s condition, Gloria hides the child in the house, never letting anyone see her. But there are still complications. The minister at her church asked her not to come there with the child. Gloria’s husband, a carpenter, never touches the baby. He won’t let Gloria sleep in the same bedroom with him because he is afraid of catching the disease. “He says the baby is going to die, and that she should die because she has a disease that could kill us all,” says Gloria.

“But nothing is as important to me as this baby. She has a right to know what it’s like to play with dolls, or to be hugged. If my husband can’t stay with me on this, then I’m going to leave him.”

It is time for Lindsey’s monthly appointment with Dr. Richard Wasserman, immunology specialist at Children’s Medical. She tries to grab Wasserman’s stethoscope and babbles like any normal baby. The baby, weighing twenty pounds, looks deceptively healthy. However. Lindsey developed a terrible case of diarrhea soon after birth. Then her heart muscles began to deteriorate. Now, Gloria constantly watches her, keeping her clean to avoid any infection: the baby goes through thirty-three diapers every two days. Gloria washes the baby’s room daily with a pine cleanser and Purex.

This is one of two AIDS babies in Dallas that Wasserman is treating; the other is the child of a hemophiliac father who received a transfusion of infected blood. At least 475 children across the country have been diagnosed with AIDS; there have been only three reported cases in Dallas County since 1981. But Wasserman estimates he will see fifteen new babies a year from mothers who have been infected by the AIDS virus-and half of those, he says, will develop AIDS themselves. There is, of course, little he can do. “I monitor the growth and optimize the nutrition of these children,” he says grimly. “That’s it.”

Lindsey and Gloria gather their things to spend another lonely month at their home. Gloria pulls out a packet of pawn shop tickets as she searches through her purse for her keys. “I’ve had to pawn off most of my possessions to pay for this child’s medical bills,” says Gloria, who has no insurance. “Look here: my pawn ticket for my 14-karat wedding band. Lindsey might be forcing us into the poor house, but that’s where I’ll go if I have to.”

Tuesday Afternoon-The Old Woman

AIDS knows no boundaries. Emma Kelly (not her real name) is retired, sixty-four years old, living by herself in a one-bedroom Oak Lawn apartment. Seventeen years ago, she says, she met a man, fell in love, and remained loyal to him. When they broke up in 1983, Emma says, she didn’t have sex with anyone else. Last April, after a doctor ran a series of blood tests on her to discover why she seemed to be growing weaker, he came across the AIDS virus. By July, Emma Kelly was in the hospital with pneumocystis pneumonia.

“Where did it come from?” she asks now, staring out her window. “When I found I had it, I called the man up at work to ask him if he knew anything. I hadn’t spoken to him for years. The woman at his office answered the phone and said, ’Why, he’s dead!’ ’Of what?’ I asked. She said he had died of some blood disease.

“Well, I went down to the city’s office of vital statistics, looked up his death record, and there it was. Cause of death; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. It took at least four years before it showed up on me.” She pauses. “I wish I could ask him how he got it,” she says.

On this afternoon, Emma is being visited by Katherine Wright, a coordinator from the AIDS Arms Network, the organization that acts as a clearinghouse for people with AIDS in Dallas. The counselors help their clients get whatever government assistance or insurance is available; they also direct them to local AIDS assistance programs. The problem, of course, is that there are barely a handful of programs to recommend.

Katherine and Emma exchange small talk. Emma seems to show few signs of the disease. Since her pneumonia, her weight has risen from 123 to 140 pounds. She takes AZT, and she spends most of the day out of bed. But to Katherine, she admits she isn’t eating well.

After Emma pays her rent from her Social Security check, she only has $29 left. She rarely goes out of the apartment because she has so little money. “Somewhere along the line,” says Katherine, “we may have to look at a less expensive apartment.”

“Oh, my.” says Emma softly. This is her final exile. “I know it’s not much,” she says, “but it’s all I’ve got to call home.”

Wednesday Morning, December 9- The Caretakers

Margaret Gallimore, the nurse who has turned her home into a shelter for dying AIDS victims, is changing the sheets on the bed, preparing for another arrival. A few days ago, another one of her “sons” died. He was James Santiso, the sixteenth AIDS patient she has kept in her home, Santiso, thirty-nine, had been with her for seven months. Since last April, the forty-five-year-old Gallimore, a nurse for twenty-three years, has been taking in bedridden AIDS patients who can no longer care for themselves and have no one to care for them.

Why does she do it? “That’s not the question,” she shoots back. “That’s just not the question. The question is why aren’t there more people doing it?”

Keeping two men at a time, she provides for all their needs. Though she works as a private duty nurse at night, she still cooks three meals a day for her “sons,” changes their sheets five or six times a day when they have diarrhea, and drives them to their doctor’s appoint nents. Sometimes, her eighteen-year-old daughter helps. Often the money runs out, and when it does, Margaret calls organizations asking for more. She is constantly bitter at AIDS organizations for not helping her more.

But now she is grieving for James. “No one knew him, no one at all,” she says. “There were no friends. His family wouldn’t accept him. He didn’t even want them to know he was dying.” In the room where James died, where he read one book after another and said little about himself, Margaret grimly changes the sheets, preparing for another who will bring with him the shadow of death. “’It isn’t right that someone has to go through this alone,” Margaret says.

Early Wednesday Afternoon-The Test

Scott saunters down the linoleum hallway of the Dallas County Health Department and into the office, no bigger than a closet, of Paula Anderson, an HIV testing counselor. He is here for his HIV test-an average of 200 people come to the health department each month for the antibodies test-and this is tar from easy for him. “First off,” he says, “I want you to know that I’m not a homosexual.” Paula nods while Scott explains that his ex-wife had been an intravenous drug user in the last few months of their marriage. She had become drug dependent and moved out to live with another man. leaving Scott, twenty-nine, to raise their three-year-old daughter.

She asks him if he’s slept with any women since his wife left. A couple, says Scott.

“Did you use a condom?” Paula asks. Scott replies that he hasn’t, but he isn’t worried-the women weren’t the type to have AIDS.

Paula gives him a hard look. “So many times I hear that,” she says. “If you could see the people who come in here every day you would say that they weren’t the type.” She leans back in her chair, makes sure she has Scott’s attention, and says: “You would be wise to assume that anyone you are dating is infected.”

For the next half hour, Paula and Scott talk analytically about sex. She tells him that condoms should be worn always, even during oral sex. “What will it mean to you,” she asks, “if you test negative?”

“Well, I’m not going to rush down to Greenville Avenue and pick up women,” Scott says. “But it would mean I’d have a future. I’d have another chance to find someone to start a relationship with and maybe someday have some more kids. I plan to stay uninfected, if that’s what you mean.”

Paula can only hope he means that. The health department estimates that at least 28,000 people carry the virus in Dallas County, and 90 percent of those don’t know they have it. Of those who come in for testing at the Dallas County Health Department, around 15 percent test positive. There are estimates that 1.4 million to 4 million Americans carry the AIDS virus but display no symptoms; the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta estimates that 30 percent to 40 percent of them will develop the disease within five years.

After the test, Scott says he won’t stop worrying until he gets the results. Or, he adds, maybe his worrying will just begin.

Late Wednesday Afternoon- The Exercise Class

If there is a single image that can instantly change one’s perception of AIDS, it is the sight of Jack Hayes leading his aerobics class. Eight men-some in peak condition, a couple of others lagging behind in the back of the room-strain to get through Hayes’s workout. A large, muscular athlete, Hayes has the men stretching, running in place, moving back and forth in the same routines that any other aerobics class would do.

Except in this class there is a difference. It might first be noticed in the encouragement the men give to one another. Or it could be picked up in the way Hayes talks to the men. “I want positive energy,” he yells. Here, at the Fitness Exchange on Inwood Road. Hayes and the other men in the class have AIDS.

People with little knowledge of AIDS often mistakenly assume that a victim must wither in bed until he dies, that there is no improvement possible from any illness that comes with the disease. But there are temporary reprieves in the battle with AIDS just as there are with cancer. After his recovery from a severe MDS-related pneumonia last summer, Hayes, an aerobics instructor before he got sick, started a class just for those with A. DS. “It was done at a time when people needed to get in control of themselves,” he says. “All we did was stand in line to get things. It was demeaning, in a way. We’d stand in line for Social Security or something, an 1 people would think we were unable to do anything.”

Hayes wants his fellow PWAs (Persons With AIDS) to believe that a sound body can strengthen the emotional and spiritual life as well. “It makes you feel something positive about yourself,” he says, “a feeling that doesn’t come so easy when you spend your days fighting a disease.”

And so, the men struggle to finish his class, their faces pale from the exertion. “The guys here could have given up long ago,” Hayes says. “They were all sick enough once to have died. But watch them. They care enough now not to stop.”

Wednesday Evening-The Support Group

This is how AIDS strikes at the heart of American life in the parlor of St. Thomas Episcopal Church, nine young adults gather to talk about their impending deaths. There are both gays and straights here, men and women. One is an engineer for a defense contractor. Another is a high-powered salesman. Another works for a financial institution. But instead of the usual Yuppie conversation that normally arises at such gatherings-getting ahead in a career, becoming rich, falling in love, building a family-the people here seem at a loss for words. After a long silence, one woman says, “1 realized last week that I was getting over the denial. I could finally admit I had AIDS. Then I started feeling a little weak, and I began to panic. Now I have to get over the fear that if I get a little cough I’ll die by the end of the day.” She stares into her lap. “My God, where does it all end?”

The weekly meeting of the Positive AIDS Recovery Group is designed to help those with AIDS learn to live with the disease instead of marking time until their death. Many here recently have learned they contracted AIDS, and they are still reeling from the news. Judy Locke, a therapist from Baylor Hospital who leads the group, reads from a devotional book: “Difficulties are of God’s making, and when they come, they should be taken as God’s confidence.” For the group here, however, the tendency is to curse God.

“I wonder why I got it,” says one gay man, “and I wonder why my lover didn’t. There is only one thing to think about something like this: why the hell me?”

Thursday Morning, December 10-The Classroom

The students in Chris Elrod’s health class take their seats at W.T. White High School in North Dallas, the ring of the tardy bell silencing their jokes and wiggles. These are sophomores, juniors, and seniors, held captive on this unseasonably warm morning by the task at hand: to learn more about AIDS.

In the Dallas Independent School District’s high school health course, required of all students, one week each semester is reserved for AIDS study. Though the school district has been criticized before for its limited coverage on human sexuality. Elrod’s AIDS class is honest.

They talk of the importance of condoms if they’re going to have sex, avoiding multiple sex partners, and avoiding exposure of the vagina, penis, anus, or mouth to someone else’s blood, urine, or vaginal secretions. Though Elrod rattles off terms describing human genitalia and sexual activity, no one smirks, And while the public at large may know little about the nature of AIDS, these kids seem to know about all the disease’s pathology.

Elrod asks: “Who can tell me what the initials AIDS, HIV, HTLV-III, and LAV have in common?”

Hands go up all over the room. Elrod points to a girl, who says, ’They all stand for the virus that attacks the white blood cells in the blood.”

“Yes,” says Elrod. “Those initials stand for the virus that particularly attacks T-4 cells in the blood. The T-4 cells are the cells that help make the antibodies that fight off infections. The AIDS virus takes the T-4 cells over.” When that happens, Elrod explains, the body’s immune system crumbles, leaving it vulnerable to a host of infections.

A student asks how much blood it takes from someone with AIDS to infect someone else. “Picture a hypodermic needle,” replies Elrod, “like the one you used when you got a vaccination. When an IV drug user uses it, there might only be a very small amount of blood left inside that needle. The blood goes back and forth in the needle. And if you used that needle and if the smallest portion of that blood entered your bloodstream, chances are you’d contract the disease.”

The Dallas school district is taking no short cuts in AIDS education. In November, the district was notified that it would receive $625,000 in federal money over the next five years to improve AIDS instruction from third grade through high school. Now, AIDS education (already a part of fifth grade, seventh grade, and the high school curriculum) will be introduced in the fourth grade and added to high school biology and home and family living courses.

The courses are obviously making an impression. As the period draws to a close, Elrod says that a person who tests positive for the AIDS antibodies may never actually develop the disease. Research is inconclusive. “But if you have AIDS,” she says, “and since at this time we have no cure, then you’re going to die.”

The class is utterly quiet.

Thursday Afternoon-The Cures

In his modest Grand Prairie office, family practitioner Dr. Terry Pulse wonders if there is a way to break the mysterious stranglehold of AIDS. Although AZT is the only drug licensed in the U.S. as treatment for the disease, researchers have been investigating dozens of other substances to reverse AIDS symptoms. There is an enormous scientific war being waged against this Andromeda-like strain of a virus-new drugs are constantly being promoted-but though there have been a lot of theories, there have yet to be any answers. Pulse’s theory involves a derivative of aloe vera, one of the oldest plants known to man. Aloe vera is mentioned in the Bible for its healing properties.

Two local researchers, Dr. William McAnalley and Dr. H. Reg McDaniel, were instrumental in discovering that aloe vera, long known as a beauty treatment, has a certain rare ingredient in it that works as an antiviral and immune booster agent-ideal for combating AIDS. McAnalley isolated and extracted the ingredient and McDaniel did the first pilot testing of it. Then, in an experimental program in 1986, Dr. Pulse started giving the extract to his AIDS patients. Though the trial program has now ended, he says his patients have shown amazing improvement. He pulls out the records of the AIDS patients (he has around sixty) whom he continues to monitor. “Look,” Pulse says, pointing to one record after the other, “their night sweats, their persistent fatigue, their documented fevers all seem to be eradicated.”

In March. McDaniel and McAnalley will deliver a paper showing their results in London at the First International Conference on the Global Inpact of AIDS, hoping their aloe verad drug will become accepted. Their research is being conducted through Car-rington Laboratories of Irving, which hopes someday to market an anti-AIDS drug. Obviously, AIDS research in Dallas, as elsewhere, is becoming a big business. It goes without saying that whoever makes the first AIDS breakthrough will not only make headlines, but a small fortune as well. Bio-Research Laboratories here is seeking governmental approval for a test for the AIDS virus that purports to give accurate results in fifty minutes. Earlier in the week, Wadley Technologies, a Dallas company that has been researching human protein drugs since the late Seventies, announced a $4.5 million joint venture with Phillips 66 Biosci-ences Corp. to develop an anti-viral drug that they hope will one day be used for AIDS treatment.

In Oak Lawn, in his kitchen that he calls “the laboratory,” a gay man with no medical training prepares AIDS drugs not yet federally approved, and secretly sells them to AIDS patients. He travels abroad to get such ingredients as isoprinosine, which many AIDS patients say makes them better.

Pulse says he’s looked at most of the underground cures, “and they border on a kind of desperate voodoo.” Until a cure comes, he says, there is only one way to halt the spread of the disease. “You’re either going to have to be celibate or faithful. People either have commitments to a relationship, to integrity and honesty, or they’re going to wipe themselves off the face of the earth.”

Thursday Night-The Bars

In the hottest singles bars in Dallas, Thursdays are always known as the “no date” nights. People flood into the nightclubs for nonstop partying, and few have come with escorts. “That’s for the weekend,” says one pretty woman who is with another female friend. Both of them are perched on stools at Pasha, the popular private dance club, and men circle them like little toy railroad trains around a Christmas tree. The women are asked to dance, they flirt with the men they like, and by the end of the evening, one of them is in a close embrace on the dance floor with someone she’s just met. Even in the era of AIDS-where casual sex now means a lot more than, “Will you respect me in the morning?”-nothing seems to have changed.

“I think everyone was scared to death for a while,” says one man at the bar. a long-time nightclub regular. “And I think everyone says that they’re not going to sleep around and all that. But when two people might have a little too much to drink and start feeling passionate toward one another, do you honestly think they’re going to start asking questions about whether they’ve had an AIDS test?”

At Sam’s, the elegant restaurant on lower McKinney, the chic crowd at the bar seems to have the same attitude. “If you stick to intelligent, upper-class women,” one man says. “I figure you’re safe.” The preppy crowd at The Chaise Lounge jokes about the problem, perhaps as a way of hiding their fear, perhaps because they cannot confront the idea that their lifestyle will have to change. “Well, I know you need to use a latex condom,” cracks one young man, “but are some colors safer than others?”

Wandering the topless bars and modeling studios is Yolanda Rivera, an AIDS educator with the county health department. She tells the women, most of whom are starved for information, about the details of the epidemic. They are usually surprised, she says, to learn that AIDS can be transmitted through oral sex. Rivera brings with her a “condom board,” showing the different condoms available and the ones that the women should use. But she doesn’t know how much her work is helping. “Some tell me that they think their bosses will kill them if they demand their customers wear condoms,” says Rivera.

Meanwhile, the scene in the gay nightclubs along Cedar Springs is as hot as ever. Some clubs, like JR’s and the Village Station, offer condoms to men, “but I think a lot of gays feel,” one bar regular says, “that if they go to these upscale gay bars, they aren’t in as much danger of getting AIDS as if they go to the cruise bars on Fitzhugh.”

One of those who looks oddly out of place in this environment is Dallas Police sergeant Earl Newsome, who for the last three years has been walkeing Cedar Springs five nights a week, working to gain the trust of the gay community and to educate everyone, including his sector’s nine fellow officers, about AIDS. Newsome goes into all the nightclubs-from Big Daddy’s, where musclebound dancers writhe and pump as young men tuck dollar bills in their bikinis, to the Round-Up Saloon, where gays dressed as cowboys (“buckarubies”) do the Texas two-step. Men gather around Newsome to swap gossip on friends, crime, and inevitably, AIDS. Because of him, fewer Cedar Springs habitués refer to cops as “Petunia pigs” or “Gay Stoppers” (a pun on Gestapo), and Newsome, who’s straight and married, tolerates no officer under his command using the words “fags” or “queers” when referring to homosexuals.

Though Sgt. Newsome constantly preaches AIDS prevention to those around him, he is not sure who is listening. Late in the evening, while slowly driving through Rever-chon Park. Newsome shakes his head in bewilderment as he passes men sitting in cars waiting for sex partners. “Don’t they know they’re playing Russian roulette with a Derringer?” he asks.

Friday Morning, December 11-The PWA House

A scandal erupts this morning in the AIDS community. It has been learned that the man who in 1986 gave $175,000 to start a desperately needed home for AIDS patients embezzled the money from a savings institution. Now the bank wants the money back, even if it has to take over the home and sell it.

“Today is a disaster, one that is going to set back AIDS care in Dallas for a long time.” says Mike Merdian, the leader of the People With AIDS Coalition that runs the twenty-unit home. Called A Place for Us, the house is the only group facility in Dallas that provides lodging for those who. because of the disease, have lost their jobs and have little means of support. A Place for Us has become nationally recognized as a model residential center for AIDS patients, but it has also gone through a storm of controversy. At its opening, neighbors picketed outside with signs that read, ’The Only Safe Sex is Abstinence.” Today there is still resentment to the project, which is home for twenty-five residents. The mailman puts on gloves before he enters the house to deliver the mail.

When Merdian, who was diagnosed as having AIDS in 1986, began raising money to open a home for AIDS patients, he found a savior in a man named Patrick Debenport, also afflicted with AIDS, who said his grandmother had left him a large inheritance. Merdian used the $175,000 given by Debenport for a down payment and renovations on a run-down apartment building in Oak Cliff. Then Merdian learned that Deb-enport’s gift came from $1.7 million that he admitted he embezzled from First Texas Savings Association. Debenport thought he was acting as sort of a Robin Hood. But First Texas Savings came to the PWA house asking for its money back; Merdian said the money had been spent.

Merdian has been suggesting the bank write off the $175,000 as a loss, considering it used it for an important cause. He says the house can barely afford to stay in operation now and cannot possibly repay the embezzled money. The bank says theft is theft, regardless of the purpose. Bank officials say they will use whatever means are available to retrieve the stolen money; they have asked the home’s leaders to sign a lien surrendering their ownership of the home.

There is further discouraging news on this Friday. At the end of the day in Houston, the nation’s first hospital devoted exclusively to AIDS will close after running up an $8 million deficit in its fifteen-month existence. The hospital, which treated 723 AIDS patients, many from Dallas, cannot attract enough governmental funding or community support. The AIDS Resource Center receives up to five calls a day from AIDS victims asking where they should move to receive experimental treatments that they cannot get in Dallas. “Just when you think there’s a glimmer of hope.” says William Waybourn, president of the Dallas Gay Alliance, “you realize how badly you’re losing the battle.”

Friday Night-The Last Visit

The chairman of the Foreign Language department at North Texas State University takes a deep breath and heads for Room 994 of Parkland Hospital. “This next one looks like a concentration camp victim,” whispers Douglas Crowder, fifty-four. But the patient lying in bed doesn’t hear him enter. Tom (not his real name) is curled fetus-like in the bed, a green plastic oxygen mask strapped around his face. It is almost impossible to imagine that this ninety-eight-pound man is alive. On his arm is a tattoo that reads, “Mom-Dad.” Once handsome and energetic. Tom was a well-known figure in the Dallas gay bars. Now, no one comes to see him.

For the past two years, Crowder has tried to visit every AIDS patient he can. Working for no pay. Crowder directs the AIDS Resource Center’s visitation and financial assistance programs, allocating money to pay bills, such as rent and staple groceries, for indigent AIDS victims. Since December 1985. he has visited 310 AIDS patients, 106 of whom have died. Another of his “boys,” as he calls them, died earlier this week, a young man named Tiny who had become blind and deaf because of the disease. Tiny had developed his own language with his friends to communicate: two fingers to the forehead meant, “I love you.”

Crowder says he doesn’t have time for close friendships anymore. He doesn’t take vacations. “The only people I know well,” he says, “are those who are dying.” Whenever he goes to the AIDS Resource Center, his mailbox is jammed with messages about people who need to be visited.

A nurse brings Tom a tray of food and props him up. With a huge effort, the young man sticks his plastic fork into the mashed potatoes. But he can’t lift it to his mouth. Crowder moves over to the bed to help him. He stares into the young man’s hollow eyes.

Tom struggles to get out a sentence. “I’m feeling better,” he finally says.

Saturday Morning, December 12- The Funeral

Outside Saint Thomas Episcopal Church, six people have gathered for James Santiso’s funeral. There is Margaret Gallimore, the nurse who kept James at her home until he died, and some of her friends. A social worker has come, and a volunteer who briefly knew James, and the Rev. Ted Karpf. They are waiting, before they start the service, to see if any of James’s relatives will come.

A car slowly pulls up: it’s James’s father and stepmother. Before his death, James had not spoken to them for more than a year. He didn’t let them know where he was and refused to tell them that he had AIDS. After his death a social worker called with the news. Now, as Margaret Gallimore introduces herself, the father, a tall man looking anguished and perplexed, says, “Lady, I’m so bitter about all of this that I don’t know if I can shake anyone’s hand.”

Karpf tells them what lames went through in his last months, the pain of his disease and his suffering. The father is not sure how to respond. “Well,” he says after a silence, “I appreciate you telling me about that.”

When they file into the little chapel, Karpf reads from the standard funeral service printed in the Book of Common Prayer. Then he delivers a eulogy about a man he hardly knew. “Perhaps with James’s death,” Karpf says, “our pain is doubled because he came to us virtually a stranger, troubled and upset. We only hope that in the end, he finally snatched a bit of peace.”

Karpf then asks if there are any who would like to share their memories of James. After a pause, James’s stepmother stands up, walks to the front of the chapel, and says, “If you see any bitterness this morning, it is because our family never stopped trying to reach out to him. He did live his life in chaos, but we never stopped trying to love him. And the bitterness has only increased because we lost our final chance to reach for him again.”

Saturday Evening-The Ellisons

For the first time, the Ellison family has decided to buy a real Christmas tree for the holiday season. “No more fake stuff.” says Ann. “I want to remember that pine smell.”

Tonight, while her husband is at work, she and her children have pulled out a box of ornaments to decorate the tree. Ann, her dark hair falling over her shoulders, has put on street clothes for the occasion. “Whenever the children see me in anything other than my gown,” she says, “they think I’m headed for the hospital.” But she is feeling better than she has in months. She actually gets hungry during the day, and color is coming back into her face. “When you feel good, it’s real easy to deny that you have AIDS,” she says. “You start to think the doctor had to have made a mistake.”

When Ann was last hospitalized, for eleven days in September, most of those close to her thought she was about to die. She could hardly breathe. A well-intentioned friend had a minister come up with a tape recorder to record her last words. A few days later on her daughter’s birthday. Ann, still very weak, sang “Happy Birthday” to her over the phone from the hospital, her mouth covered with an oxygen mask.

Ann’s two oldest children-ages seven and ten-came from her first marriage, which ended in divorce in 1981. After her divorce, she dated a lawyer for seven months, then broke off the relationship after he admitted his bisexuality. She married her present husband in September 1984 and gave birth to another baby, Two years later the man called to tell her he had AIDS. Panicked, she went to be tested and discovered that she was positive as well. Both her husband and the baby were tested for the AIDS antibodies. Both of their results were negative (though there is a chance that either of them could later test positive).

Ann’s husband has had his own burden in adjusting to the inevitability of her death, “He would stare at the diaper bag and begin to panic,” she recalls. “At times he would feel like he had to escape from it all. He didn’t know how this could have happened to his family.” They have told none of their neighbors about the cause of Ann’s illness, nor do the children exactly know-even though the two-year-old walks around the house imitating his mother’s cough or putting a Kleenex to his mouth. The Ellison family has been helped through the ordeal by the Richardson East Church of Christ, one of the few conservative Protestant churches in the city that has not shied away from an AIDS ministry.

The kids sneak into the bedroom to wrap the Christmas presents that they bought with their allowance money. With the excitement of the holiday season building, the children talk about gifts. They want to go see Christmas lights and nativity scenes. The little girl asks her Mom if she’ll feel well enough to take them to the mall. She asks so politely that tears well up in Ann’s eyes.

“Holidays are real bad for me,” Ann says later when she is alone, “because I wonder how many more Christmases I’m going to have anymore.” She looks at her small living room, with a “Home, Sweet Home” plaque hanging on the wall. “Sometimes, even now, I miss the kids. I realize that they’ll always have each other. What scares me about dying is that I’ll be alone. I just hope that they’ll remember me, and what a good mother I tried to be for them.”

Epilogue

Late in January. Ann Ellison learned shehad developed CMB, another opportunisticinfection that attacks the intestines, eyes, andbrain. She has already lost 30 percent of hersight in one eye, and says she knows she isgetting weaker. Meanwhile, others havedied. Following the funeral of James Santiso,the Rev. Ted Karpf gave funerals for fivemore AIDS victims. The future for the PWAhouse continued to look bleak. Though legalaction has yet to be taken, PWA leaders wereprivately saying there was little hope for thehome’s survival. As the number of AIDScases increased at Parkland Hospital, hospital administrators in late January beggedfor private physicians to volunteer their services at the overburdened facility. But therewere also flickers of hope. Researchers atBaylor Hospital announced they had developed a process that might eradicate theAIDS virus in donated blood. And the newDallas AIDS Planning Commission, madeup of business and civic leaders from allparts of Dallas, embarked on a six-monthstudy of AIDS in Dallas. They are determined to hammer out a plan to fight thedisease.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: When Will We Fix the Problem of Our Architecture?

In 1980, the critic David Dillon asked why our architecture is so bad. Have we heeded any of his warnings?

By Matt Goodman

Healthcare

Baylor Scott & White Waxahachie’s $240 Million Expansion

The medical center is growing to address a 40+ percent patient increase in the last five years.

By Will Maddox

Food Events

How the CJ Cup Byron Nelson Became a Korean Food Showcase

The tournament’s title sponsor, a Korean company that includes a culinary division, is literally adding new flavor to a Dallas classic.

By Deah Berry Mitchell