The End of Ownership: Why Aren't Young People Buying More Houses?

Richer couples! Cheaper mortgages! Millions of unwanted houses! Despite all this, young home owners declined for 30 years, even before the Great Recession. Here's how the American Dream shrank.

[Update: Read our round-up of your amazing comments here: "We Wish Like Hell We Had Never Bought"]

Reuters

When older generations wonder what's the matter with Millennials, they often judge their younger cohorts against such financial and social benchmarks as finding a job, getting married, and buying a home. These observations often come wrapped in weak science -- "blame Facebook for their indolence" -- or dripping with judgment -- "blame their parents for making them weak." The science is weak, but the observations are true. Fewer young people are finding jobs. Fewer young people are getting married. Fewer young people are buying homes.

Between 1980 and 2000, the share of late-twenty-somethings owning homes had declined from 43% to 38%. The share of early-thirty-something home owners slipped from 61% to 55% in that time. After the boom and bust were over, both rates kept falling. The rate of young people getting their first mortgage between 2009 and 2011 was chopped in half from just 10 years ago, according to a recent study from the Federal Reserve.

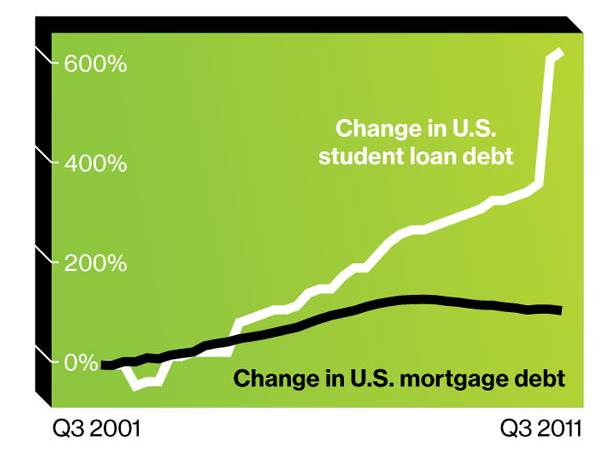

One headwind is student debt. "Close to $1 trillion, America's mounting pile of outstanding student debt is a growing drag on the housing recovery, keeping first-time home buyers on the sidelines and limiting the effectiveness of record-low interest rates," Bob Willis reported in Bloomberg Businessweek.

One headwind is student debt. "Close to $1 trillion, America's mounting pile of outstanding student debt is a growing drag on the housing recovery, keeping first-time home buyers on the sidelines and limiting the effectiveness of record-low interest rates," Bob Willis reported in Bloomberg Businessweek. This is good news and bad. Rising student debt is a sign of more students. We should want (and expect) more people to go to school in a recession. But the trepidation of first-time home buyers hurts housing sales, feeding a pernicious cycle. Bad housing numbers circulate back through the economy in the form of low residential investment, scant construction, and fewer housing services.

The decline in young home owners is a puzzling trend. Interest rates have steadily declined over the last 30 years. Mortgage lending has loosened. Women have ascended in the workplace and supplemented their spouse's earnings. How in the face of all of these positive developments did home ownership among the young keep falling?

ALL THE SINGLE RENTERS

To understand why young people are buying fewer homes, begin by asking yourself: What do you need to buy a home? We'll start with three basics. You need a mortgage. You need income for the downpayment. And you probably need a spouse. Controlling for income, gender, and education, a married person is 23% more likely to own compared to someone who is not married, and many more couples buy a home as they are preparing to wed.

"The 1980-2000 decline in young home ownership occurred as improvements in mortgage opportunities made it easier to purchase a home," Martin Gervais and Jonas D.M. Fisher write in their seminal paper Why Has Home Ownership Fallen Among the Young? So we can't begin by blaming too few available mortgages. Government interventions and mortgage innovations (remember subprime lending?) should have meant more young couples buying houses. With the rising employment and earnings of women, households should have gotten richer. That, too, should have increased homeownership. It didn't.

Instead, we can begin by blaming a shortage of couples. The decline of marriage and the increase in "household earnings risk" account for practically all of the decline in young home ownership, Gervais and Fisher conclude. So, to understand the decline of young home ownership, we have to understand the decline of marriage.

Unfortunately, the decline of marriage isn't an easier trend to unpack. I offered some thoughts here, which I'll try to sum up in a sentence: Higher college-graduation rates have delayed marriage for many, and as women moved toward financial equality with men (and as technology made it easier to be alone) financially motivated marriages went down, and contently single ladies went up. "A decline in the incidence of marriage mechanically lowers home ownership," Gervais and Fisher write.

But that's not all.

FREAK OUT!

It's not just the marriages. It's also the money.

Marriage rates for the 25-44 set fell by 15 percentage points between 1980 and 2000. But this only accounts for half of the decline in Gervais and Fisher's model. The other half comes from stagnating wages, and the worry that the dynamic economy will destroy a couple's earnings with inflation, recession, or job loss. Basically: People aren't buying homes because they're freaked out about the economy.

The freak-out transcends gender and class, and it crystallized within a generation. In one survey comparing early Boomers (born in the late-'40s and '50s) and late Boomers (born in the late-50s and -60s), overall economic uncertainty in the second group rose by 11% for college graduates and 52% for high school graduates. Uncertainty about the value of college rose, too.

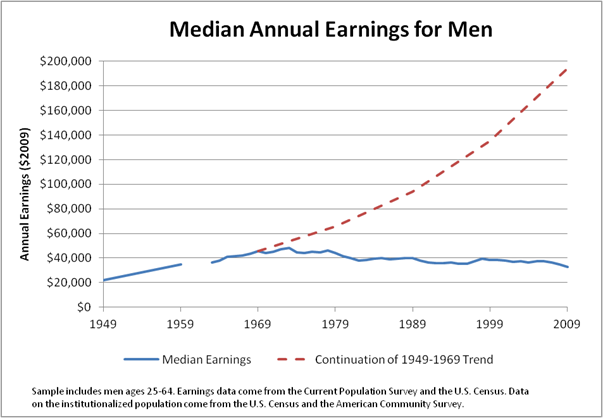

It's not all in their heads. Between 1950 and 1970, wage growth was something special. Earnings grew 44 percent per decade -- more than three times faster than they've grown over the last 30 years. If that trend had continued, the typical working guy would be earning a $194,000 per year today. (He's not.) Michael Greenstone, the director of the Hamilton Project, prepared for us this graph to illustrate the difference between where median earnings for men were headed, and where they've really gone. This is what the uncertainty gap looks like.

BROKE AND CROWDED

Houses are expensive. I'm not going to win an award for this observation, but there it is. The problem with expensive things, like houses, is that you can't buy them with only your own money. You need somebody else's money, too. This is why mortgages exist.

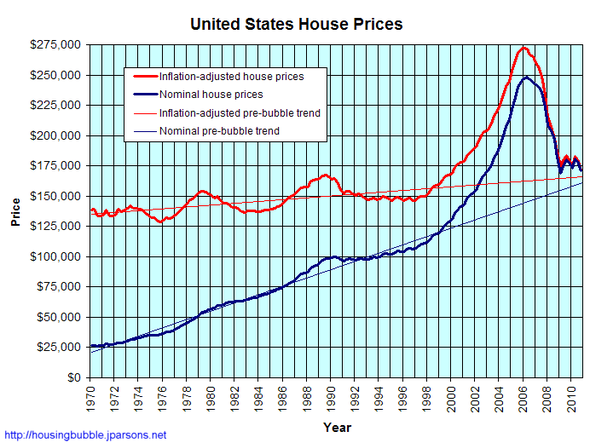

In the years before the Great Recession, mortgages bloomed thanks to financial innovation. This was creative destruction, in that order. First came creation. The subprime boom was, in Karl Smith's words, "a technological innovation that allowed millions of households to switch out of the market for multi-family homes [like duplexes] and mobile homes and into the single family market ... [pushing] up the price of existing single family homes." Then came destruction. This happened:

Before the Great Recession, we spread apart -- out of cities and into the suburbs and single-family homes. After the Great Recession, we came together. A quarter of young adults have moved back in with their parents for a significant period of time. More have shacked up in apartments and tripled up on roommates to split the costs. In the last three years, mortgage interest rates have fallen tremendously, creating a good opportunity for people with means to get in on a house. But who's got the means and opportunity? Unemployment for twenty-somethings is twice as high as the national average. Banks have tighter credit conditions on all but the highest-quality borrowers.

You can focus on the loudest numbers and conclude that young peoples' aversion to home owning is an overreaction to a unique recession. Housing prices have fallen by a third in some cities. Couples have had a few years to pay off their debts. Mortgage interest rates are historically tiny. Could there possibly be a better time to buy?

Maybe not. But if the last 30 years have taught us anything, it's that planning for the future is an act of faith. Supply chains and software eat our jobs. Financial wizardry eats our savings. The cost of insuring against these risks -- that is, both college and literal insurance -- is rising. "It feels like anytime we hit around $20,000 something terrible or some unexpected thing happens," Steve Kinney, a Brooklyn resident, told the New York Times last year. He's part of a new renters society, and rental prices are rising now that housing prices aren't. Three in five net jobs in the last two years have gone to people in their twenties and lower-thirties, "a crucial rental group," according to an analysis of Labor Department data by G. Ronald Witten, an apartment firm consultant.

It's no wonder that in an environment that punishes the long-term faithful, more young people are planning month to month.

><