This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

The California schools where the kids are all the same race, all in one map

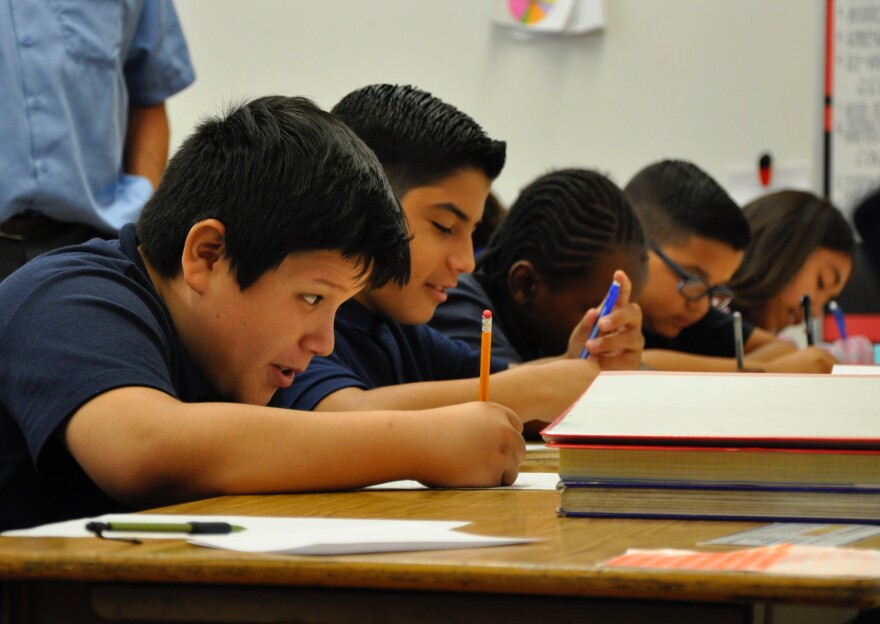

Across Los Angeles and Orange counties, one out of every five Hispanic children — 259,000 kids — attended a school in 2014 where practically every other child shared their race: the student body was at least 95 percent Hispanic.

And in the 550 or so of those most racially isolated schools in Southern California — as rated by an analysis published Sunday by data journalists at the Associated Press — students are less likely to have met state standards in reading or math.

In its analysis, the AP reported measures of school segregation across the U.S. have regressed to levels not seen since the days of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, or since the 1970s, when courts across the nation began ordering districts to institute busing programs to integrate their schools.

That segregation persists in Southern California isn't news to many educators, experts and practitioners in the region's schools, like Alberto Retana, who leads the non-profit Community Coalition of South Los Angeles.

Retana readily rattled off school segregation's causes, both historic and systemic: "Red-lining, [housing] covenants, chronic disinvestment in where development happens, white flight, capital flight — it’s totally not surprising that our schools are an indicator of our society as a whole."

But the Associated Press's findings do shed fresh light on where to find racially homogenous schools across California.

In fact, put the AP's data on a map, and it shows pockets of racially isolated schools spread south and east of downtown Los Angeles, scattered across inland L.A. and San Bernardino counties and clustered in Santa Ana and Oxnard:

(Click here view this map in its own window.)

How to use this map

This map displays around 900 of the schools in California the Associated Press rated as the state's most racially isolated — meaning, schools in which a single racial group was heavily over-represented.

Using federal government data from 2014 and a U.S. Census methodology, the AP calculated a racial isolation measure — an "entropy" score — for every school.

These scores range from zero to one. A school with an entropy score of "zero" is entirely composed of a single racial group. A school with an entropy score of one would be evenly mixed between racial groups.

This map shows the 900 or so schools across California with entropy scores closest to zero, indicating one racial group essentially prevails there. Around 500 of these schools — charter, magnet and district-run — are located in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties.

To view schools with higher entropy scores — and thus, more racially mixed student populations — adjust the slider on the bottom of the map. When a broader range is selected, the darker-colored dots represent more racially homogenous schools.

What this map shows

Almost without exception, in Southern California, the schools the AP identified as the most racially isolated were heavily populated by Hispanic students. (When referring to the AP's findings, we're using the term "Hispanic" only because the data on which this analysis was based did not use the term "Latino.")

That's no surprise to Ann Owens, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Southern California who studies segregation. Owens notes that Los Angeles County's child population is 61.3 percent Latino. In the L.A. Unified School District, Latinos comprise nearly three-quarters of the student body.

"Every map I’ve ever seen of racial composition in L.A. of neighborhoods looks like this," Owens said.

To scholars like Richard Rothstein, the map reinforces the conclusion that residential segregation prevents public school integration — and unless housing is integrated, schools will remain racially isolated.

"We've spent about the last 30 years trying to evade the obligation and obvious necessity of desegregating neighborhoods," said Rothstein, a research associate at the Economic Policy Institute.

In their national analysis, AP journalists found that charter schools were heavily racially isolated. Charters were more likely than traditional district-run schools to be non-white. In California, charter schools' entropy scores appeared to mirror those of district schools.

The degree of racial isolation in schools matters a great deal, because "school segregation exacerbate achievement gaps," said Carrie Hahnel of Education Trust-West, a non-profit advocacy organization that focuses on measuring and narrowing the gulf between privileged and underprivileged students.

"When we take those students," said Hahnel, the organization's deputy director for research and policy, "that have had fewer opportunities in their communities — fewer preschool opportunities, less access to healthcare, prenatal care even — and concentrate those children with disadvantages in the same schools … and then provide those very schools with fewer resources — less qualified teachers, less-rigorous coursework, fewer librarians — what you’re going to do is exacerbate the inequality."

What this map doesn't show

Several educators and experts noted the map of the Associated Press's racial isolation scores, as mapped above by KPCC, can be misleading.

For one thing, the AP's entropy index shows schools in which only one racial group is overwhelmingly represented. But Retana noted his organization runs after school programs on campuses in South L.A. in which two racial groups are overwhelmingly represented: Latinos and African-American students.

Such schools would not receive entropy scores that are quite as low, even though these schools are arguably still segregated — if not racially, then certainly socio-economically.

"It’s an opportunity to talk about Latinos, but it’s also a stark reminder of the work we still have yet to do with our black students," said Retana.

On the opposite end of the scale, it's not clear to Owens that schools with more racially mixed student populations — and thus, higher entropy scores — represent models of integration.

For instance, a school that's evenly divided between white, black, Latino and Asian students may have a high entropy score, but it also wouldn't reflect the demographics of any Southern California county.

"In a county that's 60 percent Hispanic, [if] you have a school that’s 25 percent Hispanic, it means somewhere else, Hispanic kids are over-represented in a school," Owens said. "If we’re going to create integrated schools across L.A. County, they need to reflect what L.A. County looks like."

What should we do about it?

Rothstein, who recently published a book on segregatory housing policies, said integration efforts such as magnet programs — which aim to draw privileged children into underprivileged schools — may be steps in the right direction.

But they're only "marginal" steps, he said: "Unless we desegregate neighborhoods so that families can live in high opportunity neighborhoods, we’re not going to have integrated schools."

It's a solution that would take years to realize, Rothstein said — and there's no single policy change that can bring it about.

"In the short term, though," said Retana of the Community Coalition, "I think that we should be concerned about the quality of education, not the composition of the schools. We have to do both, it's not either or, but … my worry when we talk about racial isolation is that we then focus on how to integrate the schools and we never talk about the quality of instruction, programming, resources."

In Los Angeles, particularly, school choice has added another wrinkle to the integration challenge. Many education advocates say students and parents need more options if their default, neighborhood school is a poor fit.

But "just because you give people choice, that’s not going to achieve integration on its own," said USC's Ann Owens. "It’s putting the onus on families to sort themselves perfectly, and they’re not going to do that."

Take charter schools, Owens said: "Are charter schools themselves providing a racially balanced experience? And are charter schools contributing to segregation in the traditional public system by pulling white kids out? On both of those scores, the narrative [among segregation scholars] has generally been that charter schools are not achieving integration."

But Carrie Hahnel of Education Trust-West said the AP's findings — and others like it — lay down a challenge for privileged families in particular.

"We can say we value diversity," she said, "but when it comes to a parent’s own child — to many in the white community — there’s only so much tolerance that we have for integration and diversity.

"Until parents," Hahnel added, "are willing to make a different kinds of choices for their own children, it’s going to be difficult at a micro level to solve this problem. But also, at a macro level, if our politicians are not hearing a collective demand from voters and from families for a different kind of schooling experience, I think this is going to be difficult to change."