The Man Who Kept Trader Joe's Whimsical

As the West Coast chain expanded eastward in the ‘90s, former CEO John Shields—who died recently at the age of 82—sent out a cohort of upbeat Californians as cultural emissaries.

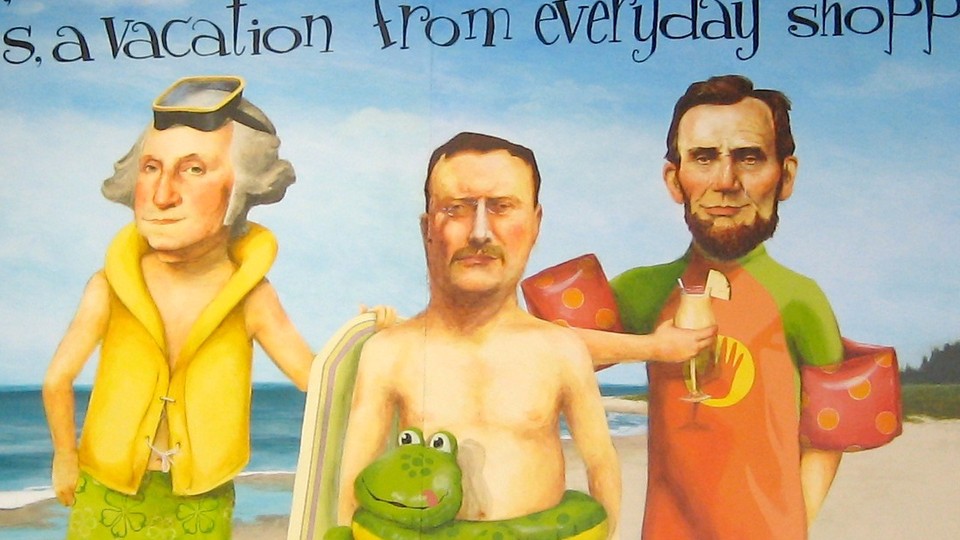

At the Trader Joe’s I frequent here in Washington, D.C., there is a painting of a teary-eyed John Boehner on one wall and a WPA-style mural of protesters outside the Supreme Court demanding better cheap wine on another. At the Trader Joe’s in Philadelphia's Center City, each checkout line is named for a local thoroughfare: Race St., Market St., Walnut St. And back in Northern California, the Trader Joe’s two blocks from the house I grew up in has a painting of a historic stretch of downtown. In every city I’ve lived in, I’ve marveled at how Trader Joe’s can feel at once local and national.

How does it manage to pull off that duality? With a lot of calculation. Trader Joe's started out as a small chain in Southern California in the '60s, and its ambitions remained small until the early '90s, when the company began eyeing the East Coast. Executives were wary, though, that the chain's distinctly Southern Californian warmth would get lost in transit. That concern was routinely headed off under the guidance of CEO John Shields, who started in that role in 1989, when the chain had only 27 stores. By the time he retired in 2001, there were 158 Trader Joe's locations, revenues had increased roughly 15-fold, and the brand's quirky novelty hadn't faded. Shields died late last month at the age of 82.

The whimsical, upscale shopping culture that he was instrumental in preserving is one that has been with Trader Joe’s since the brand was first dreamed up by its founder, Joseph Coulombe, in 1966. Over the years, the chain eschewed some of the technologies their competitors unquestionably adopted, such as PA systems (Trader Joe’s has its staff communicate by ringing bells) and checkout scanners. And even when Trader Joe’s did cave in on checkout scanners, it did so mindfully, phasing them in with pilot programs and making sure to quiet the machines’ checkout chimes so shoppers and cashiers could still keep up a conversation.

This was the folksiness that Shields aimed to keep intact as Trader Joe’s made the jump from regional to national. After looking for fresh territory, Shields eventually came to the conclusion that the 500-mile span from Boston to D.C. would be particularly hospitable to Trader Joe’s. The company had long pursued educated consumers over wealthy ones, and Shields knew this region had more colleges than any other part of the country. (Coulombe, the chain's founder, once said that Trader Joe’s envisioned its prototypical customer as “an unemployed Ph.D.”)

As Shields went forward with the expansion in the late ‘90s, slight tweaks were made to the product line—there’s more demand for kosher products in Long Island than in Pasadena—but most of the efforts went into transposing Californian peculiarity onto a relatively brusque Northeastern culture. Shields enlisted roughly 25 bubbly Trader Joe’s managers, Hawaiian shirts and all, to go train the new East Coast employees. (“They’ve kind of got the droid thing going,” one goateed emissary told The Los Angeles Times of the shoppers from Scarsdale, New York.) Shields even flew out to interview new managers himself, rejecting any candidate who didn’t smile within 30 seconds of shaking his hand.

A bit paradoxically, it was this insistent stubbornness on a laid-back culture that produced Trader Joe's remarkable results. The stores stock about five times fewer products than most grocery stores, and produce a revenue-per-square-foot that is three times the industry norm. And, perhaps because it pays its staff well relative to other grocers, Trader Joe’s has an employee turnover rate that's a fifth of some competitors'. The company now has more than 400 stores, and, if a 2005 estimate is any indication, might bring in around $8 billion this year, though the company doesn't make those figures public.

Trader Joe’s has been around for nearly 50 years, yet no competitor has successfully encroached on its clientele. Some industry experts say this is the case because Trader Joe’s is selling not food, but worldliness and playfulness. "There really only is one Trader Joe's," one analyst told The Los Angeles Times back in 1997. "They buy a lot of close-outs, they buy wine and spirits and unusual items in small batches, and then they romance the hell out of them in their brochures."