The Anti-Vaccine Movement Is Forgetting the Polio Epidemic

On the 100th anniversary of Jonas Salk's birth, his son Peter talks about the backlash against vaccines and other human factors that make it difficult to eradicate deadly viruses.

It started out as a head cold. Then, the day before Halloween, 6-year-old Frankie Flood began gasping for breath. His parents rushed him to City Hospital in Syracuse, New York, where a spinal tap confirmed the diagnosis every parent feared most in 1953: poliomyelitis. He died on his way to the operating room. “Frankie could not swallow—he was literally drowning in his own secretions,” wrote his twin sister, Janice, decades later. “Dad cradled his only son as best he could while hampered by the fact that the only part of Frankie’s body that remained outside the iron lung was his head and neck.”

At a time when a single case of Ebola or enterovirus can start a national panic, it’s hard to remember the sheer scale of the polio epidemic. In the peak year of 1952, there were nearly 60,000 cases throughout America; 3,000 were fatal, and 21,000 left their victims paralyzed. In Frankie Flood’s first-grade classroom in Syracuse, New York, eight children out of 24 were hospitalized for polio over the course of a few days. Three of them died, and others, including Janice, spent years learning to walk again.

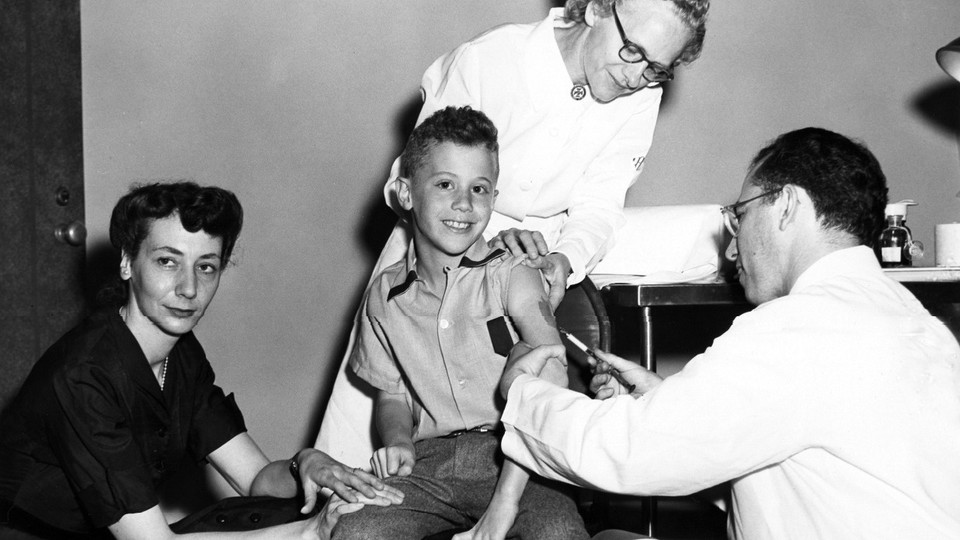

Then, in 1955, American children began lining up for Jonas Salk's new polio vaccine. By the early 1960s, the recurring epidemics were 97 percent gone.

Salk, who died in 1995, would have turned 100 on October 28. He is still remembered as a saintly figure—not only because he banished a terrifying childhood illness, but because he came from humble beginnings yet gave up the chance to become wealthy. (According to Forbes, Salk could have made as much as $7 billion from the vaccine.) When Edward R. Murrow asked him who owned the patent to the vaccine, Salk famously replied, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

I recently spoke with Salk’s oldest son, Peter, an accomplished medical researcher in his own right who spent years working alongside his father at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Peter told me about his father’s late-in-life HIV research and the ethical concerns he explored in such books as Man Unfolding and The Survival of the Wisest. Peter also spoke with impressive thoughtfulness about today’s anti-vaccine movement and reflected on why so many Americans came to distrust life-saving vaccines such as the one his father helped bring to the world.

Jennie Rothenberg Gritz: What sort of person was your father?

Peter Salk: He was a kind person. He really cared about people. In his personal interactions, he did everything he could to uplift whomever he was interacting with. As things went on with polio, there was obviously a great deal of controversy. But he wasn’t one who wanted to engage in battles, even when people attacked him for the approach he was taking.

in May 1955 (AP)

Rothenberg Gritz: What gave him the confidence to keep working on his vaccine when so many people were telling him it couldn’t be done?

Salk: That was sort of his nature. He just didn’t accept dogma if he didn’t understand it. When he was in medical school, taking a course in microbiology, the professor spoke about two bacterial diseases—tetanus and diphtheria—that are caused by toxins that bacteria produce. You can inactivate those toxins chemically and use them to produce a protective immune response. In the next lesson, the professor said that when came it to viral illnesses, you couldn’t do that. You needed to have a living virus to induce immunity that would protect against the disease. My father didn’t understand why one thing would be true for a couple of bacterial diseases but not for viral ones. He thought you ought to be able to do same thing with a virus: inactivate it and then induce an immune response without any risk of the vaccine causing the disease itself.

Rothenberg Gritz: A lot of people thought Albert Sabin’s live-virus vaccine was the better way to go, right?

Salk: Yes, Albert Sabin was an established figure in the field. He was not one to welcome someone with different views about things. And indeed, most people felt that his oral vaccine, where you use a weakened version of the live virus, was going to be the most effective.

Polio gets into the body through the mouth and then grows in the intestines. Sometimes it will travel into the blood stream, then into the nervous system. It’s there—in the spinal cord or the brain—that the virus causes paralysis. To be protected against paralysis, all you need are antibodies circulating through the bloodstream. That’s the kind of protection my father’s injectable vaccine provides.

But in 1962, the Sabin oral vaccine was introduced on a wide scale. It ultimately replaced the injected vaccine in this country entirely. The problem with the Sabin vaccine is that the weakened virus can revert back to a dangerous form in some people. As a result, the wild polio virus was completely gone at the end of the 1970s, but for decades we continued to have somewhere between 8 and 12 cases each year that were caused by the vaccine itself.

In this country, the decision was finally made in 2000 to go back to the injectable vaccine. On a global level, there was an eradication initiative that started in 1988. They primarily used the oral vaccine. By 2012, the number of reported, naturally occurring polio cases was down from about 350,000 in 1988 to 223. But the WHO estimates that something on the order of 250 to 500 cases of polio are caused every year by the live vaccine itself.

claiming that the vaccine for measles, mumps,

and rubella causes autism and even death.

(AP)

Rothenberg Gritz: People have been concerned by the idea that vaccines can cause disease in healthy children.

Salk: There are some subtleties to this. With pertussis, for instance, the old vaccine was based on using the whole killed organism. That was very effective, but because there were a whole lot of different kinds of proteins that were all mixed up, there were some side effects. Later on, they developed a so-called acellular pertussis vaccine, where you use purified materials from the bacterium. It doesn’t produce as strong or long-lasting an immune response—people need to have booster shots when they’re adults, for instance. But it doesn’t cause the same side effects.

When my own son Michael was born 31 years ago, the whole-cell vaccine was still in use. Whooping cough was essentially gone in this country by that time, so from one perspective, why should we take the risk of causing a high fever or other side effects in our own child? I know I certainly thought about this a lot. But I just couldn’t bring myself to take advantage of the good that other people had done by immunizing their kids—to take a free ride, so to speak. Michael did end up developing a fever. But I couldn’t have lived with my decision if we hadn’t given him the vaccine.

Rothenberg Gritz: Some vaccine opponents argue that as long as children live healthy lifestyles, they can either avoid illnesses like polio or recover quickly and develop “natural immunity.”

Salk: No. I wouldn’t hesitate to use very strong words about that. Of course it’s a good thing to live a healthy life, to keep the body strong and well-rested. I won’t rule out that it can help to protect against some types of disease. But when it comes to these organisms that can be very damaging to people, I think it’s wishful thinking to imagine that a healthy lifestyle can protect against infection.

And what we see is that many diseases are starting to come back. Measles is recurring; whooping cough is recurring. The kids whose parents are choosing not to immunize them are at risk, but so are babies and kids who might not be able to be vaccinated for one reason or another. These kids are no longer having the same benefit of herd immunity. Their level of protection is now eroding.

Rothenberg Gritz: Do you remember when you first started hearing about widespread opposition to vaccines?

Salk: I don’t remember exactly when, but it first came to my attention through some of my friends. I read some of the materials they sent me, and it just was really hard for me to follow some of the logic—particularly when it came to the polio vaccine, which I knew something about. People were claiming that it was all a myth, that the disappearance of polio had nothing to do with vaccines.

The reality is that back in 1954, there was a huge double-blind study involving 1.8 million schoolchildren. The results were clear-cut: If you got the polio vaccine, you were protected; if you didn’t, you were not. When you have that kind of data, you just can’t say that the disappearance of polio is due to other things. What strikes me is—I don’t know quite how to put this, but it’s like there’s an epidemic of misinformation, and we’ve got to inoculate the public against it.

Rothenberg Gritz: Why do you think this misinformation has spread so widely?

Salk: Part of it is that people have become complacent because these diseases aren’t rampant anymore. During the polio epidemic, people were really frightened. This was a disease they didn’t understand, whose appearance they couldn’t predict, and it had terrible effects on kids. Swimming pools and movie theaters were closed. It’s easy to forget this now. Also, these days, there are a lot of concerns about living naturally and not wanting to be exposed to things that are made in a laboratory.

But there are probably other forces at work. Back in the 1950s, people really looked to science and medicine as something that would make their lives better. But once the fear of these diseases began to subside, people started looking at other large-scale forces in the world—the Vietnam War, the government, and so on—and wondering, Can we trust large institutions? Can we trust pharmaceutical companies? I think that that’s something that’s driven people also: a sense of alienation.

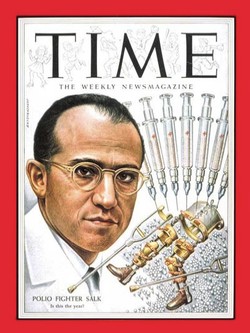

photo of “Polio Fighter Salk” above the caption,

“Is this the year?”

Rothenberg Gritz: Do you think it would help if there were more scientists like your father—celebrity researchers who communicated directly with the public and appeared on the covers of major magazines?

Salk: My father was a public figure, but his peers didn’t always like that. It wasn’t part of the scientific tradition to communicate directly with the public the way he did. Scientists were supposed to communicate only through meetings and publications. But there were some points where my father felt it was really important for him to communicate directly with people, to help them understand what was taking place, to have their expectations appropriately in line. This wasn’t something his fellow scientists really appreciated.

Rothenberg Gritz: He also decided not to patent the vaccine. Why not?

Salk: I don’t think it ever really crossed his mind. He was totally driven to create a vaccine that would protect kids against polio. Indeed, the March of Dimes looked into a patent. I don’t think they had any evil reasons. I’ve seen records of some of correspondence that took place, and I suspect that they wanted to ensure that the drug would be manufactured correctly. They kept trying to get my father’s attention because they needed to get information to patent it, and it was incredibly frustrating for them when he didn’t want to put his attention on it. It was just a different world back then.

Rothenberg Gritz: In your own experience, how have patents and profits affected the pharmaceutical industry?

Salk: I can recall my experience with AIDS treatments. Back at the end of the previous century and the beginning of this one, I was involved in helping introduce treatments in Africa and Asia—that’s back when AIDS drugs were $10,000 or $15,000 a year. There were countries where the health budget would be something on the order of $4 per person per year. With prices in this range, how would it be possible for these drugs to be used in such countries? Finally, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria came along and helped put some money in the picture. President Bush came in with PEPFAR. And finally, some generic manufactures in India and Brazil drove the price down with cheaper versions of the drugs.

These complex forces have brought things to where at least you’ve got a manageable system. But those systems were put in place without any provision for beefing up the health care infrastructure in these countries. They pay for drugs, but they don’t pay for the training of medical professionals. You see it with Ebola; the currently affected countries in Africa have totally inadequate health care systems. What are they supposed to do? They’re not able to protect their people from these diseases spreading. And now, because we’ve not helped sufficiently to get them on their feet, we’re being exposed ourselves to the consequences.

Rothenberg Gritz: You and your father spent a number of years working on an AIDS vaccine. Why is it so much harder to create than a polio vaccine?

Salk: There are only three versions of the polio virus. With HIV, the virus is rapidly changing, as happens with influenza also. The flu shot you get one year isn’t the same as the next one. It’s the same sort of thing with HIV. If you develop an immune response, the virus can mutate rapidly to evade that.

Also, polio is an acute illness. You have the infection and then it’s gone. With HIV, once you’re infected, it gets into your cells. Its genetic material is now integrated into your own genetic material. Once the virus has gotten a foothold like that, so far it hasn’t turned out to be possible to get rid of it.

Rothenberg Gritz: So what was your father trying to do?

Salk: As a first step, he wanted to take advantage of the fact that there’s such a long period between the time when a person is infected with the virus and the time the immunodeficiency symptoms develop. Over the months, over the years, the virus is chipping away at your CD4 T-cells. Eventually, they get depleted to such an extent that you no longer can defend yourself against different pathogens, etc.

What he wanted to try was a very simple approach: As with polio, he used a killed virus. The idea was that you might be able to boost the activity of a particular part of the immune system in people who were already infected with the virus to help kill off the cells that were infected with HIV, thereby slowing the progression of the disease.

The first clinical trial in infected patients began in 1987. The project continued until somewhere around 2007. Nothing practical has come of it, but I later went back and did a statistical analysis, based the subset of the data I had on my computer or in my paper files. It turned out the vaccine had highly statistically significant effects on slowing the progression of disease, on the decline of these CD4 T-cells. So it seems to me that more could be done based on this approach. A good starting point might be to do an independent meta-analysis in a more official and comprehensive way.

in Karachi, Pakistan. In 2012, a gunman killed

five women who were in the process of giving

polio vaccinations to children. (Reuters)

Rothenberg Gritz: Polio itself still hasn’t been totally eliminated in some countries. What’s holding that up?

Salk: The people who are working on polio eradication are doing everything they can, but there are still countries where there are conflicts, religious differences, cultural differences, political differences—and these are the countries where some kids haven’t been able to be reached with the vaccine that’s been used. India finally eliminated the wild virus a few years ago. Pakistan is the greatest problem right now, with all its internal turmoil. The disease still persists in Afghanistan, but that’s largely a result of what’s happening across the border in Pakistan. Nigeria has also so far never eliminated the wild virus.

It’s so interesting to me. We’ve now got vaccines that should be able to get rid of this virus forever. But until we can deal with these human interactions in a more constructive way, we’re not going to get there. That’s what holding things up. It’s not the scientific level; it’s the social level.

Rothenberg Gritz: Your father spent a lot of time thinking about those problems.

Salk: Yes. After the polio vaccine was introduced, he decided to establish a new institute. But from his earliest writings, it was clear that he wasn’t just interested in researching vaccines, diabetes, and so on. He was interested in dealing with the problems that arise from man’s relationship to man—problems that can’t be solved in the laboratory.

The way he saw it, the universe has gone through three stages of evolution. First, there was the pre-biologic realm, where you had the evolution of matter: atoms, molecules, stars, galaxies. Then life appeared: Biological evolution was driven by a need to survive. Finally, humans came on the scene. Look at us—where is the evolution happening now? The world around us is so hugely complex, and that complexity comes from us.

The fundamental element that is evolving now in our sphere of existence is not matter, not life—it’s consciousness. The unit here is the mind. My father called this the metabiologic realm; it’s driven by choice. He often said that we are the products of the process of evolution, and we have become the process itself. It’s our responsibility to be making wise choices.